The Great Entrance is essentially the transporting of the consecrated gifts from the Prothesis to the Holy Table. The act of presenting the gifts to be consecrated has always been characteristic of the Christian Liturgy. Justin Martyr notes it in his brief description of the Liturgy in the second century: “At the conclusion of the prayers we greet one another with a kiss. Then, bread and a chalice containing wine mixed with water are presented to the one presiding over the brethren. He takes them and offers praise and glory to the Father of all, through the name of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and he recites lengthy prayers of thanksgiving to God in the name of those to whom He granted such favors.”143

The common opinion is that originally the presentation of the gifts to be consecrated was done by the Faithful, and that later on the clergy assumed this task as the Liturgy became more clericalized. Liturgical scholars like Josef Jungmann have noted that such processions of the Faithful to present the gifts to be offered “flourished in the Occident for over a thousand years.”144 While this may have been true for the West, the East never knew such an “offertory of the Faithful.” According to a liturgist who has studied the issue in-depth, “the Great Entrance is simply a development of the original transfer of gifts by the deacons; there is no convincing evidence that there was ever an offertory procession of the faithful in the East... It would seem, then, that contemporary Byzantine practice is a fairly accurate reflection of what has always been the Oriental custom regarding the offerings of the faithful: the people bring to the priest their prosphora with a list of the living and dead for whom they wish him to pray, whenever they happen to arrive in church. These gifts remain in the skeuophylakion or prothesis until after the Liturgy of the Word, when they are then transferred to the altar in the Great Entrance.”145

The manner in which the gifts are presented has today become one of the climactic moments of the Liturgy. The gifts are taken out the north door of the Iconostasis with candles, incense, icons, liturgical fans and the cross, and there is a long procession through the Church which ends in front of the Royal Doors. The development of the Great Entrance into its present grandeur started roughly around the fifth century and reached its present form by the fourteenth.

The chant used during the Great Entrance is called either the Cherubic Hymn or the Cherubicon: “We who mystically represent the Cherubim, and sing to the life-giving Trinity the thrice-holy hymn, let us now lay aside all earthly care, that we may receive the King of all, who comes invisibly borne up by the angelic hosts. Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia.”

This hymn was certainly in existence before it was formally introduced into the Liturgy in 574 by Emperor Justin II. Though he doesn’t give the texts, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite around the year 500 mentions that hymns were sung during the Great Entrance: “The hierarch, having said a sacred prayer at the divine altar, begins the censing there and then makes the round of the entire sacred place. Returning to the divine altar, he begins the sacred singing of the psalms and the entire assembly joins him in this....Some of the deacons stand on guard in the sacred place to ensure that the doors are kept closed. Others perform tasks appropriate to their order. The chosen deacons, along with the priests, put on the divine altar the sacred bread and the cup of blessing. And all this is preceded by the singing by the entire gathering of the hymn of universal faith (i.e., the Creed, which was introduced in the late fifth century). Then the divine hierarch says a sacred prayer and bids holy peace to all. All the others exchange the ritual kiss and the mystical reading of the sacred volumes is concluded (i.e., the diptychs, or “folding boards,” which listed the names of those either living or dead who are commemorated during the Liturgy).”146

It is quite possible that one of these hymns could have been an early version of the Cherubic Hymn. Only a few decades later, Patriarch Eutychius (552-565, 577-582) in his Sermon on the Pascha and the Holy Eucharist objected to the inclusion of a “psalmic chant” where “the people say that they bear in the king of glory and refer in this way to the things being brought up, even though they have not been consecrated by the high-priestly invocation.” Many commentators on the Divine Liturgy believe this is a reference to the existence of the Cherubic Hymn just prior to 574. Other liturgists, however, believe that Eutychius was probably not referring to the Cherubic Hymn. For one thing, the “king of glory” would be a misquotation of the phrase “king of all;” and it seems unlikely that the patriarch would garble the very phrase which he found objectionable and which he heard sung whenever he celebrated the Liturgy. Moreover, its characterization as a “psalmic chant” has lead many to believe that Eutychius was talking about one of the biblical psalms being used at an inappropriate place during the Liturgy. Liturgical scholars like Robert Taft suggest the psalm was Psalm 23 (LXX) where, in its Septuagint reading, the phrase, “the king of glory”, occurs several times in verses 7-10: “Lift up your gates, ye princes, and be ye lifted up, ye everlasting doors; and the king of glory shall come in. Who is this king of glory? The Lord strong and mighty, the Lord mighty in battle. Lift up your gates, ye princes; and be ye lifted up, ye everlasting doors; and the king of glory shall come in. Who is this king of glory? The Lord of hosts, He is the king of glory.” It may be that our present Cherubic Hymn was introduced to replace the singing of this psalm during the Great Entrance. Many meanings have been ascribed to the Cherubic Hymn. Some commentators simply say that it refers to the entrance of Christ escorted by the heavenly hosts. Others interpret the entrance in a paschal context, as the triumphal entry of Christ into Jerusalem, or as Christ being led to His Passion and burial. Sometimes it is seen as His descent into Hades, or His entrance into His kingdom. The hymn itself, though, is quite simple and straightforward: Let us set aside all the cares of life, that we may receive the King of all, invisibly escorted by the angelic hosts.

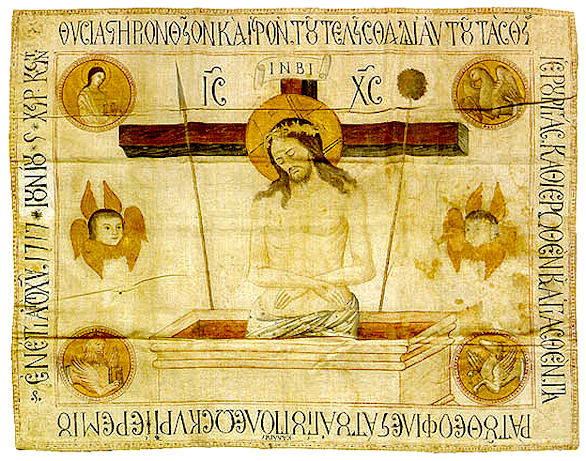

At the beginning of the Cherubic Hymn, the

antimension, a cloth containing holy relics, is unfolded by the priest and

laid on the Holy Table. This practice seems to be an echo from the ancient

Church, which would frequently celebrate the Liturgy on the graves of the

martyrs. Originally, the antimension was used in place of the holy table, as

the word “antimension” (literally, “in place of a table”) means. It is now

used, however, in every Divine Liturgy whether there is a consecrated altar

or not. The bishop gives the antimension to the priest as a way of

delegating his authority to the priest. In the ancient Church, when there

would be only one congregation celebrating the Eucharist in a city, the

bishop was the one who celebrated the Mystery and the presbyters would

simply assist him. But as the number of Christians grew, it became necessary

for bishops to delegate their authority to the presbyters in order to allow

several Liturgies to be celebrated in different locations on Sunday. This

can be seen as early as the year 110, when Saint Ignatius, the bishop of

Antioch, wrote to the church at Smyrna, “Let no one do any of the things

appertaining to the Church without the bishop. Let that be considered a

valid Eucharist which is celebrated by the bishop, or by one whom he

appoints.”147 The antimension

denotes this delegation of authority to the priest, as a sort of “license”

to celebrate the Eucharist in the bishop’s diocese. The laying out of this

“authority” to celebrate the Eucharist signals the end of the Synaxis and

the actual beginning of the Liturgy of the Faithful.

================================

143 Justin Martyr, The First Apology, 65. Emphasis added.

144 Jungmann, The Early Liturgy, 117.

145 Robert Taft, The Great Entrance (Rome:Pontifical Institutum Studiorum Orientalium, 1978), 11, 34. 146 Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, chapter 3. 147 Ignatius of Antioch, Epistle to the Smyrnaeans, 8:1. Emphasis added.