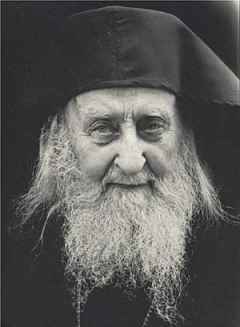

Archimandrite Sophrony was born in 1986, to Orthodox parents in

Tsarist Russia. From childhood he showed a rare capacity for

prayer and as a young boy would ponder questions heavy with

centuries of theological debate. A sense of exile in this world

spoke of an infinite always embracing our finitude. Prayer

entails the idea of eternity with God. In prayer the reality of

the living God is yoked with the concrete reality of earthly

life. If we know what a man reverences, we know the most

important thing about him- what it is that determines his

character and behavior. The author of His Life is Mine was early

possessed by an urgent longing to penetrate to the heart of

divine eternity through contemplation of the visible world. This

craving, like a flame in the heart, irradiated his student days

at the State School of Fine Arts in Moscow. This was the period

when a parallel speculative interest in Buddhism and the whole

arena of Indian culture changed the clef of his inner life.

Eastern mysticism now seemed to him more profound than

Christianity, the concept of a supra-personal Absolute more

convincing than that of a Personal God. The Eastern mystic’s

notion of Being imparted overwhelming majesty to the

transcendental. With the advent of the First World War and the

subsequent Revolution in Russia he began to think of existence

itself as the causa causens of all suffering and so strove,

through meditation, to divest himself of all visual and mental

images.

His studio was at the top of a tall house in a quiet part of

Moscow. There he would labour for hours on end, straining every

nerve to depict his subject dispassionately, to convey its

temporal significance, yet at the same time to use it as a

spring-board for exploring the infinite. He was tortured by

conflicting arguments: if life was generated by the eternal, why

did his body need to breathe, eat, sleep, and so on? Why did it

react to every variation in the physical atmosphere? In an

effort to break out of the narrow framework of existence he took

up yoga and applied himself to meditation. But he never lost his

keen awareness of the beauty of nature.

Daily life now flowed on the periphery, as it were, of external

events. The one thing needful was to discover the purport of our

appearance on this planet; to revert to the moment before

creation and be merged with our original source. He continued

oblivious to social and political affairs- utterly preoccupied

by the thought that if man dies without the possibility of

returning to the sphere of Absolute Being, then life held no

meaning. Occasionally, meditation would bring respite with an

illusion of some unending quietude which had been his

fountain-head.

The turmoil of the post- Revolutionary period made it

increasingly difficult for artists to work in Russia, and in

1921 the author started to search for ways and means of

emigrating to Europe- to France, in particular, as the centre of

the world for painters. En route he managed to travel through

Italy, looking long at the great masterpieces of the

Renaissance. After a brief stay in Berlin he finally reached

Paris and flung head, heart and soul into painting. His career

made a satisfactory start: the Salon d’ Automne accepted his

first canvas and the Salon des Tuileries, the elite of the Salon

d’ Automne, invited him to exhibit with them. But on another

level all was not going as he had expected. Art began to lose

its significance as a means to liberation and immortality for

the spirit. Even lasting fame would be but a ludicrous

caricature of genuine immortality. The finest artifact is

worthless when considered against the background of infinity.

Little by little it dawned on him that pure intellection, an

activity of the brain only, could not advance one far in the

search for reality. Then suddenly he remembered Christ’s

injunction to love God ‘with all thy heart, and with all thy

mind’. This unexpected insight was as portentous as that earlier

moment when the Eastern vision of a supra-personal Being had

beguiled him into dismissing the Gospel message as a call to the

emotions. Only that earlier moment had struck dark as a

thunderclap, while now revelation illuminated like lightning.

Intellection without love was not enough. Actual knowledge could

only come through community of being, which meant love. And so

Christ conquered: His teaching appealed to his mind with

different undertones, acquired other dimensions. Prayer to the

Personal God was restored to his heart- directed, first and

foremost, to Christ.

He must decide on a new way of living. He enrolled in the then

recently opened Paris Orthodox Theological Institute, in the

hope of being taught how to pray, and the right attitude towards

God; how to overcome one’s passions and attain divine eternity.

But formal theology produced no key to the kingdom of heaven. He

left Paris and made his way to Mount Athos where men seek union

with God through prayer. Setting foot on the Holy Mountain, he

kissed the ground and besought God to accept and further him in

this new life. Next, he looked for a mentor who would help

extricate him from a series of apparently insoluble problems. He

threw himself into prayer as fervently as he previously had in

France. It was crystal-clear that if he really wanted to know

God and be with Him entirely, he must dedicate himself to just

that- and still more entirely than he had to painting in the old

days. Prayer became both garment and breath to him, unceasing

even when he slept. Despair combined with a feeling of

resurrection in his soul: despair over the peoples of earth who

had forsaken God and were expiring in their ignorance. At times

while praying for them he would be driven to wrestle with God as

their Creator. This oscillation between the two extremes of hell

on the one side and Divine Light on the other made it urgent

that someone should spell out the point of what was happening to

him. But another four years were to pass before the first

encounter with the Staretz Silouan which he quickly recognised

as the most precious gift Providence ever made to him. He would

not have dared dream of a such a miracle, though he had long

hungered and thirsted after a counselor who would hold out a

strong hand and explain the laws of spiritual life. For eight

years or so he sat at the feet of his Gamaliel, until the

Staretz’ death when he begged for the blessing of the Monastery

Superior and Council to depart into the ‘desert’. Soon after,

the Second World War broke out, rumours of which (no actual news

filtered through to the wilderness) intensified his prayer for

all humanity. He would spend the night hours prone on the earth

floor of his cave, imploring God to intervene in the crazy

blood-path. He prayed for those who were being killed, for those

who were killing, for all in torment. And he prayed that God

would not allow the more evil side to win.

During the war years the

desert felt remarkably more silent and withdrawn than of wont,

since the German occupation of Greece bared all traffic on the

sea around the Athonite peninsula. But the author’s total

seclusion ended when he was urged to become confessor and

spiritual father to the brethren of the Monastery of St Paul.

Staretz Silouan had predicted that he would one day be a

confessor and had extorted him not to shrink from this crucial

form of service to people- service which necessitates giving

one-self to the supplicant, accepting him into one’s own life,

sharing with him one’s deepest feelings. Before long he was

called to other monasteries, and monks from the small hermitages

of Athos, anchorites and solitaries turned to him. It was a

difficult and heavily responsible mission but he reasoned to

himself that it was his duty to try and repay the succour which

he had received from his fathers in God, who had so lovingly

shared with him the knowledge granted to them from on High. He

could not keep their teaching to himself. He must give freely of

what he had freely received. But to be a spiritual counselor is

no easy task: it involves transferring to others attention

hitherto destined for oneself, looking with imaginative sympathy

into other hearts and minds, contending with my neighbour’s

problems instead of my own.

After four years spent in a remote spot surrounded by mountain

crags and rocks, with little water and almost no vegetation, the

author assented to a suggestion from the Monastery of St Paul to

move into a grotto one their land. This new cave had many

advantages for an anchorite-priest. There were many hermits in

the desert and they tended to settle close to one another,

though hidden from sight by bounders and cliffs. Here, besides

being completely isolated, there was a tiny chapel, some ten

feet by seven, hewn out of the rock-face. But winter was a

trying time. The first downpour would flood the previously dry

cave and then every day for perhaps six months he was obliged to

scoop up and throw outside some hundred buckets of water soaking

his cough. Only the little chapel stayed dry. There he could

pray, and keep his books. Everywhere else was wet. Impossible to

light a fire and warm up something to eat. In the end, after the

third winter, failing health compelled him to abandon the grotto

which had afforded the rare privilege of living detached from

the world.

It was now that the idea came to him of writing a book about

Staretz Silouan, to record the precepts which had so helped him

to find his bearings in the wide expanses of the spirit by

instructing him in the ways of spiritual combat. To carry out

this project he would have to go back to the West- to France,

where he had felt more at home than in any other country in

Europe. His first intention was to stay for a year but then he

found that he would need more time. Working in difficult

conditions, he fell dangerously ill and a serious operation left

him an invalid, causing him to lay aside all thought of

returning to a desert cave on Mount Athos.

The preliminary edition of his book concerning Staretz Silouan

he roneo-typed himself. A printed edition followed in 1952.

Thereafter the translations began: first into English (The

Undistorted Image), then German, Greek, French, Serbian, with

excerpts in still other languages. The reaction of the ascetics

of the Holy Mountain was of extreme importance to the author.

They confirmed the book as a true reflection of the ancient

traditions of Eastern monasticism, and recognised the Staretz as

spiritual heir to the great Fathers of Egypt, Palestine, Sinai

and other historic schools of asceticism dating back to the

beginning of the Christian era.

Archimandrite Sophrony felt convinced that Christ’s injunction,

‘keep thy mind in hell, and despair not’, was directed through

Staretz Silouan to our century especially, drowned as it is in

despair. (Are not the ‘perilous times’ come, ‘when men shall be

lovers of their own selves…unthankful, unholy…trucebreakers,

false accusers…despisers of those that are good…lovers of

pleasures more than lovers of God; having a form of godliness

but denying the power thereof…ever learning, and never able to

come to knowledge of the truth?). He believed, too, that as

Staretz had prayed for decades with such extraordinary love for

the human race, entreating God to grant all mankind to know Him

in the Holy Spirit, so men would love the Staretz in return. The

Russian poet Pushkin claimed that no monument would be necessary

to keep alive remembrance of him- his fellow countrymen would no

long cherish his memory for he had sung of freedom in a cruel

age, of mercy to the fallen. Had not the Staretz in his humility

rendered a still nobler service to humanity? He taught us how to

drive away despair, explaining what lay at the back of this

terrible spiritual state. He revealed to us the Living God and

His Love for the sons of Adam. He taught us how to interpret the

Gospel in its eternal aspects. And for many he made the word of

Christ real, part of everyday life. Above all, he restored to

our souls a firm hope of blessed eternity in the Divine Light.

Throughout the book “His Life is Mine”, Archimandrite Sophrony

reflects the teaching of his spiritual father. Not all of it

will be intelligible at first perusal- in fact, it is not easy

reading on any reckoning. Form must be sacrificed to content

when the translator is caught in the uncomfortable limbo between

languages; and in a work of this kind the author is so often

speaking across a semantic chasm. Few of us have any inkling of

the life described in these pages. But close study will make us

familiar with the Athonite ascetic’s manner of living, and then

we can with profit try to apply some of the lessons learned to

our own case. Grace, which is God’s gift of holiness, depends

upon man’s attempt at holiness.

In 1959, accompanied by his disciples, he left for England,

where he founded the Monastery of Saint John the Baptist. Having

been a coenobitic monk and a hermit, he was now ‘a witness to

the light’ (cf. John 1:7,8) at the heart of the world. In 1993,

11th July, Elder Sophrony humbly and peacefully rendered his

soul to God.

Today, the Monastery of Saint John the Baptist is a place where

hundreds of pilgrims from all over the world are welcomed; it is

not only one of the main centres from which Orthodoxy is

radiated in the West, but also one of the strongest affirmations

of the universality of Orthodoxy.

Archimandrite Sophrony Sakharov (2001) (2nd ed.)

His Life is Mine. Introduction. New York: St Vladimir’s Seminary

Press.

Archimandrite Sophrony Sakharov (1998) Words of Life- preface.

Essex: Stavropegic Monastery of St. John the Baptist.