|

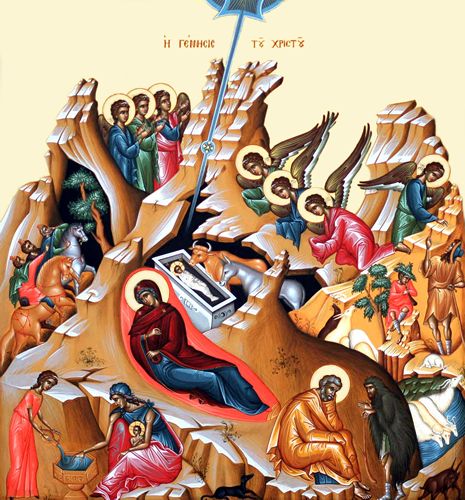

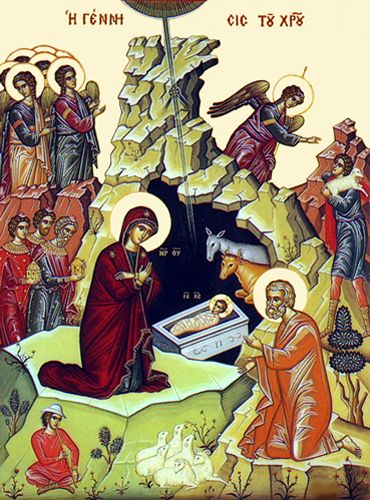

We shall continue our lessons, with the depiction of the Nativity that we began with the last time, but not with exactly the same icon. Today's icon has certain variations and elements that the previous one doesn't. I will only remind you of some of them, in a bare outline, beyond the basic principles that I had given you. I had mentioned the darkness that is depicted in the icon - that space where darkness and the shadow of death are, as described by the prophet Isaiah - in other words, the world, in which Christ was born. I also remind you of the two animals therein, which represent the Christians of Gentile descent and Judean descent, as this has been described biblically by Micah and by the prophet Elijah. Christ is always depicted among two reasonless animals, which represent all of mankind; likewise (reasonless) were the Judeans, who, albeit in possession of a portion of the truth, had acted unreasonably. But even the Christians who had come from within the Gentiles had also acted unreasonably, hence Christ being "acknowledged" among the two animals, which appear here, in the center... ….The infant Christ is wrapped in funereal swaddling strips. What is implied here, is that Christ was born, in order to die for us. This is not merely a depiction of the triumph of the Nativity of Christ; The Nativity of Christ is the preparation for Easter - that is why Christ is laying ("sleeping") inside a grave-like cradle. He is not asleep in just any bed, which is what leads our train of thought to the stage of the Resurrection. Here, we see the Virgin; the All-holy Mother. the Virgin always bears - in every hagiographical expression - three tiny stars, one on Her head and one on each shoulder. They are eight-pointed stars. The three stars declare that the All-holy Mother was a Virgin before, during and after giving birth; that She is indeed a Virgin. And the eight points of each star signify the mystery of the "Eighth Day". God created Man in seven "days". On the seventh day, Man failed. And God - through His plan of Divine Providence and Christ's condescension - thereafter inaugurated the opus of the Eighth Day of Creation. That was precisely the objective of Divine Providence; and that is why the All-holy Mother is a part of the plan of Divine Providence: She ministers to that mystery, and that is also why She is depicted with those stars... Let me also remind you that hagiography also expresses a certain theology. You see, we have the Holy Bible as our source, as well as the Hymns of our Church - which are hymnological renditions of theology - and we also have Icons, which are pictorial representations of theology; therefore what we are dealing in here is theology. That is why quite frequently we even depict festive Troparia hymns with Scriptural expressions. For example, the Troparion for the Nativity says: "A Virgin is seated, mimicking the Cherubim..." and in this icon, we can actually see the Virgin in a manner "seated and mimicking the Cherubim" . See, Her arms are in fact positioned Cherubim-style, She is in a stance of prayer and She is seated or kneeling, but not standing. The seated position always implies a certainty in our theology; There is a text in the Old Testament - I think it is by the prophet Hosiah - who had said in reference to God: "You are the seated One; we shall be eliminated. You are the One Who is seated, for all Time..." Can you see the comparative element here? Seated, not standing, like one who is transient, temporary. Therefore the seated position signifies secureness. God is seated. That is why we don't depict the saints in a seated position. It is incorrect and is a romantic expression to depict a saint enthroned. Only Christ or the All-holy Mother can be depicted enthroned - in other words, the most "extreme" persons only. A seated person represents an absolute certainty. You see, the All-holy Mother - after Her acceptance of that event of Divine Providence that was to be realized in Her person - did in fact become our most holy Mother; in other words, She was rendered irreversibly impervious to sin. That is why She too is portrayed in a seated position. Now let us examine the peripheral, surrounding elements in the icon. There are the angels, which are singing the glory of God; all angels are necessarily depicted with a band around their head. They are always depicted with long hair and always with a ribbon that holds it - and this is a dogmatic element, not a secondary one. And what does that ribbon signify? Well, the heavenly powers, like the terrestrial, logical beings - that is, the human beings - are animals-beings with reason. Man is a "deifiable" animal. Angels have their minds turned permanently towards God and that is their sustenance. Even the therapeutic method of the Orthodox Church is directed towards a human that is ill, and, broken down as he is, to turn his mind likewise towards God. That is his therapy. Turning towards God is his therapy. Angels, therefore, possess this quality absolutely - that turn towards God - and especially after the day that the demons fell, but the angels didn't. What we celebrate on the 8th of November is that stance by the angels - and we also cite in the Divine Liturgy the words "let us stand fast, let us stand with fear" - when the angels did not fall, like Lucifer did. Following this stand, Saint John of Damascus in one very important dogmatic text - an extremely important dogmatic teaching, both succint and substantial, titled "A Precise Exposition of the Orthodox Faith" - had said (but it is also a dogmatic tradition of the Fathers) that the angels after this incident became impervious towards sin; they can never fall thereafter, because they had "stood fast". This could have been the case with Man also, if he hadn't succumbed to the devil's provocation. That is why the ribbon around the angelic head symbolizes gathering; because that internal magnitude or abstract magnitude of the word "nous" - and not simply "the brain" - cannot be depicted, so, in hagiography, it is with the aid of external symbolisms that I express those things that are not visible. We, for example, are able to depict prayer hagiographically. But if you ask an artist to "paint a prayer", one might paint something entirely naturalistically, say, a person praying in a forest. Another might paint something more abstract, like a streak of red colour on a white canvas. I don't know how he might depict it. But we do not resort to naturalistic or abstract means. We express significant meanings with symbolisms. Thus, because the angels have their minds "gathered" and focused on God, we place a ribbon around their plentiful head of hair (which denotes the plentiful charismas that they possess). That too is a dogmatic element. There are no angels depicted without a ribbon tied around their head. We will notice this detail in other icons with angels also. Then, we see the three Magi in the icon. The word "Magos" should not be confused with the demonic acts of magic, of invocation of demons, either for good or for evil purposes, that is, the erroneous, worldly discerning between "black" and "white" magic. "Magi" means wise men. That is how they were called at the time. They were scientists, and they were bringing three gifts as you know... gold, frankincense and myrrh. Those gifts are also dogmatic elements. They brought gold to the infant Christ, because He is a King. Gold would logically be given to a king. Frankincense, because He is God. And Myrrh? Well that fragrance called myrrh was the material used for anointing the dead - according to Hebrew tradition of course, but the anointing with myrrh was also according to other external traditions of the Hebrew world: the anointing - the chrismation - of the deceased was also for reasons of cleansing, just like we do. We too clean our dead before their burial. They anointed Christ with myrrh and aloe. Therefore He is God and King, and He is the One Who was to die for us. So you see, the gold, the frankincense and the myrrh are all specific dogmatic elements. We also notice the depiction of Joseph the Betrothed. Joseph the Betrothed of the Holy Mother, who had been tempted and was hesitant about accepting to undertake the Holy Mother or not. Joseph is depicted at the bottom edge of the icon. Notice here, that those who are at the center of a liturgical act are portrayed at the center of the icon. Those who are only ministering to that mystery are at the edge of the icon. And the central figure is always Christ, in a manifold portrayal such as this one - but not in a single person portrayal of a saint, where the saint is the central theme. Joseph, like the Holy Mother, are both officiating in this mystery. They are officiators of the mystery or ministers (the ancient Greek word for minister implied the assistant, the servant). You will notice that here, even the Holy Mother is not exactly in the center of the icon. Joseph is a little more to the side and below. They are both ministers to that mystery. They are attendants to that mystery. Normally, those who minister to a mystery are commemorated on the day following the main feast-day. The Holy Mother is commemorated on the 26th of December. Thus, the day after the Birth of Christ, we celebrate -note this carefully- the synaxis of the Theotokos. It is a feast-day of the Theotokos, and, in order that it does not overlap with the feast-day of Joseph the Betrothed and his feast-day be lost, it has been transferred to the Sunday immediately after, when we celebrate Joseph the Betrothed along with two other prophets. This is how we commemorate the ministers of a mystery. You see? John the Baptist was decapitated on the 29th of August, which is the day of his martyrdom, but we commemorate him par excellence on the day of the Epiphany, on the 7th of January, because he had officiated at the Mystery of the Baptism. He had ministered to it. These are theological meanings that are very essential, and the saint is a minister. The Greek word for minister is ypourgos (ypo + ergo), and its verb means "to subserve". You should pay attention to the profound expression of the verbal formations of the Greek language. He is a "subservant" of the mystery. He ministers to the mystery always, and he is a deacon thereof. But there aren't many obvious ministers of the mystery. There is Joseph the Betrothed, and - note this - in Orthodox hagiography we never depict the so-called "holy family" with the measures of the West. We do not have any "holy family". We have the Holy Mother, who is ever-virginal. She always preserved Her virginity, and Joseph was a "subservant" of the mystery of the Nativity. We never depict a "holy family" as Christ, the Holy Mother and Joseph, except only in one incident: their flight to Egypt. Here, the Holy Mother is astride a donkey with Christ, and Joseph is once again ministering to them, by leading the donkey and following them, in order to help them along the way. That is not the "holy family". It is the depiction of the flight to Egypt, with its own theological specifications, like every icon has. We then see the bathing of the divine Infant - a totally misunderstood depiction. In fact, this depiction, especially after the 17th century when dogmatic, Roman Catholic theological perceptions infiltrated the Orthodox realm - which began from Russia and even reached the Holy Mountain - was painted over in practically all of the Catholicons (main churches of the Monasteries) on the Holy Mountain. The depiction of the bathing had been painted over, because they had considered it unacceptable to portray the bathing of the Divine Infant. That was a dogmatic mistake. Now, all icons have been cleaned of their whitewashed surfaces. You see, even on the Holy Mountain, no-one is the exclusive expresser of Orthodoxy. Orthodoxy has its own truths, which is the generality of the truth, and not what just one place says. No place is "Vaticanian" in Orthodoxy. They had regarded it as unacceptable for Christ to be depicted naked and being bathed. But then why did the hagiographer insert that scene in the icon? The iconographer had included it, to show what was done to all infants: when they were born, they were bathed. Remember, it is on the eighth day that the final cleansing takes place - the complete cleansing. Christ was a perfect human, and He was to undergo everything human. Except for sin. If Christ had not been bathed because He was God and as such did not need to be washed, then He wouldn't have been a perfect human. In that case, we would be falling into a dogmatic error, as that would have meant the Christ does not save. Because Christ as a perfect human saves Man and perfects him. If He was something more than us in His human nature, He would not have needed to sleep, or to eat. But all these were possible by Christ - they are a given fact - however, He wouldn't have been a perfect human; He would have been a superhuman who would not be saving mankind. It is the phrase by Gregory the Theologian: "whatever is not assumed cannot be ministered to". And Christ had assumed everything - note here - all of our irreproachable passions. Christ had passions, but only the irreproachable ones. What are the irreproachable passions? Hunger is one such passion, but it is not a sinful one. Thirst, sleep are also irreproachable passions. Reproachable passions are precisely the corruption of those irreproachable passions. Gluttony, as compared to hunger. That is what saint John of Damascus and other Fathers of our Church tell us. And of course we see the shepherds that are portrayed in the icon in various ways. It is the human presence - the human glorifying presence at the moment that Christ arrived. And from the sky above, we see the Divine Light descending - the Uncreated Light, which illuminates that mystery of the Nativity. I had mentioned the last time that we depict everything that was revealed to us - everything that was seen, actually seen by us. Pay attention: seen by us, because we had indeed seen Christ. But we state that "we saw Him". Do not say that "they saw Him". All of us see Christ, if we are living in the Church. The Church is a Body. What one of us has seen, the others have also seen. The body's experience is unique. In other words, if I wished to acquire the feel of a cold or hot metallic vessel and were to use only the cells of my sense of touch on it, then by merely touching it with those cells alone, my entire body will acquire the experience of heat. It is not necessary for my entire body - the millions of cells that my body is made of - to wrap itself around that vessel in order for my entire body's cells to acquire that egotistic experience of what I have understood to be "hot". That is our egotistic experience speaking, when we say "but I didn't see Christ". If we are living in the Church, it is our experience also. We therefore depict whatever we have seen. We have seen Christ, therefore we depict Him. We have seen the Holy Spirit, "in the semblance of a dove", therefore we depict it as such. But God the Father we have never seen, therefore we never depict Him. I will stress that detail. We are practical, we are realists and deeply theological at the same time, and therefore what we haven't seen, we do not depict. We have seen Cherubim? We depict them. We have seen Seraphim? We depict them. We have seen Angels, Archangels? We depict them. We have not seen what Thrones, Principalities, Powers, Virtues, Dominions, Authorities and other celestial powers are like, therefore we do not depict them. Question: Excuse me, but there is an icon that depicts God in a portrayal..... Reply: We never accept the portrayal of God the Father. Question: Then why … …. …. Reply: They do it, because they are not familiar with the theology of icons. We never depict the Holy Trinity as Father, Son and Holy Spirit - and the Father as an old man with long hair. It is wrong. The Father never revealed Himself to us. "You shall not see My countenance and live", the Father had said. Nobody sees the Father. Christ Himself had appeared according to the capacity of human perception. And so did the Holy Spirit, by appearing "like a dove". But Christ -Who appeared and was incarnated as a human- is one thing, and the Holy Spirit -Who was not incarnated as a dove- is another thing. The Holy Spirit appeared "like" a dove, and not incarnated "as" a dove. That is the dogmatic approach for this icon. We move dogmatically on this point, and no-one can alter the theology of the Icon with his own particular perception of it.

Source: http://www.floga.gr/50/04/2005-6/02_2005111104.asp

Translation: K.N. |