We

shall continue with our lessons on the theology of icons, with the depiction of the

Annunciation of the Theotokos. The event of the Annunciation is

described in Luke's Gospel, in which the Evangelist described

numerous events that are linked to the Theotokos, and especially to

the birth of Christ. The birth of Christ is also described by

Mark the Evangelist, but the details that pertain to these events

are described by Luke, who had met the Theotokos in person and had

learnt of those events - for example of the Annunciation - directly

from the Holy Mother.

But what is important is the theological approach to the Icon. In

the icon of the Annunciation we can see the Archangel Gabriel and

the Holy Mother in that unique encounter! The icon that I personally

regard as most probably the best depiction of the Annunciation, is

the icon of the Holy Mother of the Annunciation of Ohrid. The region

of Ohrid lies just above the Prespes lakes - today's Skopje. This is

an exquisite icon, by an unknown artist.

Let us examine the icon for a moment. Some of the facts that I gave

in previous analyses of the Angel and the Holy Mother will be

approached today in a better manner. First of all, the Angel

is announcing an event. Given that he is announcing an event and is

in motion, his legs as we can see in the icon are wide apart. This

denotes the presence of movement. In other instances, we shall see

angels who are not likewise in motion, and whose legs are static.

Whatever we know about angels, we owe it to the Holy Bible.

According to Scriptural standards, they are "functional spirits,

sent forth to minister". In other words, they have two things.

Firstly, they are functional spirits, they minister to God, and

secondly, they are sent forth to minister. They have a mission. God

sends them forth, to do something in the world. That is their role.

For the other heavenly hosts we do not have much information. Most

of the things that we know are about angels and archangels.

While we do know that the other hosts are called principalities,

thrones, powers, virtues, etc., nevertheless, we do not know what

their functional roles are. We know very little about the Cherubim

and the Seraphim, which appeared in the space of the Old Testament.

But we do have more - and more frequent - appearances by angels and

especially archangels. You should remember, that Michael of the

Archangels appears in the Old Testament and Gabriel of the

Archangels appears in the New Testament. Thus, when you see an

Archangel in the space of the New Testament - and even if you don't

know his name - it is the Archangel Gabriel. The Archangel

Michael usually - but not necessarily exclusively - appears in the

Old Testament. Of course in events that mar our Church's history, we

have a few variations. We have the miracle at Chonais, which we

commemorate in September and was performed by the Archangel Michael.

But anyway, this is a general view of things. That is why you should

also know that from a liturgical point of view, the order in which

icons are placed in the Sanctum, the Royal Gate has two doors. The

one to the right - as we see it - and another to the left. You may

have noticed that the door to the left is the only one that is used

during the Divine Liturgy. Whereas in all the services, the deacon

exits through the left door and re-enters the Sanctum through the

right door, when the Divine Liturgy begins, the right door ceases to

be used altogether. Only the left door is used, through which the

Priests pass, holding the Precious Gifts. This signifies that this

door which is liturgical use during the moment of the New Testament,

is the door of the New Testament. Whereas the other door -

which is constantly in liturgical use and is abandoned, and no

longer used during the Divine Liturgy - is, symbolically speaking,

the door of the Old Testament. That is why the face of the Old

Testament door - to the right, as we see it - is always adorned with

an icon of the Archangel Michael, who is the Archangel of the Old

Testament, and on the other door, the icon of the Archangel Gabriel

is always depicted.

Angels, therefore, are "functional spirits, sent forth to minister".

If angels are ministering, as in the icon of Christ's Baptism where

they are ministering to His Baptism, we will notice that they are

depicted as motionless. Their legs are not apart. If their legs are

depicted apart, striding, that will denote they have been "sent

forth". This same movement of the legs can also be observed in

depictions of the Apostles. The Apostles are also in motion and they

are ministering to God. If they are on a mission, their legs will be

depicted in a striding position. If they are depicted as

ministering to the mystery of divine providence, their legs will not

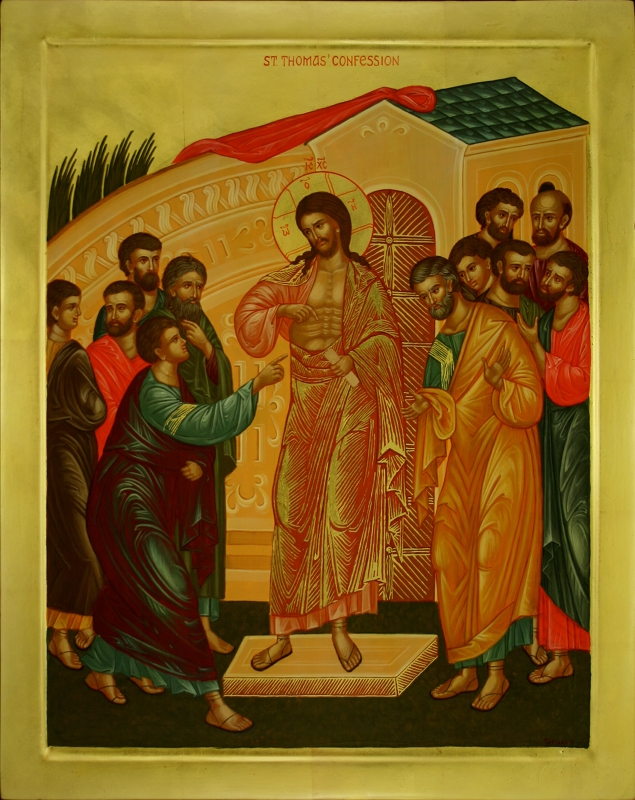

be apart. In the icon of the Ascension, or the icon of Thomas's

touching Christ's scars, you will notice that the disciples are

depicted to the left and the right. Thomas is at the centre of the

icon touching Christ's scars, and the remaining disciples are on

either side. You will notice that half of them are with their legs

in motion and the other half with their legs motionless. They

cannot depict an Apostle with legs in motion and simultaneously

motionless; given that the Apostles are one body, half of them are

depicted in motion, with their legs in a striding position, and the

other half are motionless, with their legs together. In this way,

they are stating that they are simultaneously in motion, but also

motionless ministers. Which is what we also are, essentially. In

Orthodoxy, we do not ask ourselves "What is better?" To stand still

or be in motion? What should concern us, is to be on the move

per the measures of the mission that God wants us to undertake, and

be motionless per the measures of hesychasm and the stance of

watchfulness and prayer. Both these measures comprise a balance in

Orthodoxy. We never have any form of absolutism. In other

words, if someone were to state: "I will withdraw as a hesychast,

without making any move, any action", then he would be living

Orthodoxy correctly. Both these aspects therefore alternate.

In the icon, the Archangel Gabriel is "sent forth" to the Holy

Mother, which is why his legs are depicted apart, in motion. As you

can see, he has one arm outstretched - he is announcing something to

Her. If he were a functioning spirit and ministering to a mystery

(as you can see in an icon of the Baptism), his arms would not have

been outstretched. In fact, they would have been covered with a

cloth. If the hand is exposed, it is indicating something. God

is telling him to say something. The hand is not his; he is lending

his hand, to God. That is what takes place in the Divine Liturgy. If

you have noticed, we priests wear an external garment which is

called a

phelonion, and it covers our arms. Our arms remain covered. This

signifies that we do not have arms of our own. And if we are to do

something, we do it in the manner that the Church tells us,

according to God's instructions. In other words, we do not use our

arms the way we want, in order to make gestures of sorrow, joy,

triumph, victory, etc.. The priest places his arm under the

phelonion when blessing the people, or the precious gifts, or when

saying "Peace to all". Nothing more. So you see that a priest

participates in angel fashion, to the extent of his measures, as do

all the people of God, during the performance of the Liturgy.

In motion, but also motionless. In the icon, therefore, the Angel

has his arm outstretched, his legs set apart, given that he is

presently "sent forth" to minister. You see how significant

these things are! You cannot abolish them.

Now let us observe the Angel's head. You will notice that the Angel

has a headband holding back his head of hair. The headband in

hagiography is (I could say) the carnal, material expression of the

noetic prayer. The

Angel is concentrating the wealth of his mind (I can't actually

describe his intellect and mind) in the presence of God. That is why

he is wearing the headband. What interests us is his concentration.

And note something else - that the head is not depicted in profile,

or face-on. The depiction is a three-quarter view of the face,

so that we can see both his eyes. What is of interest to us, is to

see both his eyes. And we can see this in images of all the saints.

The Angel is also holding a staff. You should never portray this

Angel with that romantic kind of expression - the way that the

Vaticanian style does, carrying a lily in his hand. There is

no tradition that reports any such detail, nor does the Holy Bible

mention that the Angel carried any staff in his hand. To us, the

staff has a theological symbolism. A staff was always the object

used by messengers when they had to make an announcement. Up

until recently, even in our villages, a town crier would come out

and strike a stick against the cobblestones in the street, and shout

out that this or that event was going to take place. The staff

signifies that the Angel has come to announce something. He is not

holding a flower to enhance the moment, or to offer it as a gift to

the Holy Mother. That is a mistake. It is a romantic approach to the

event. And our Church has never indulged in the romantic approach to

the matter, but always approaches it with solemnity. Our

Church seeks to inspire solemnity with Her art forms, and not to

display romanticism. That is why we differentiate ourselves

altogether; both in music and in portrayal. Two par excellence arts.

There are other forms of art of course, such as woodcarving. But, as

with these two par excellence art forms, the same applies with

woodcarving. We produce simple, uncomplicated woodcarvings. We

do not carve in any baroque or rococo style, which are highly

ornate, and overloaded, for the purpose of making an impression on a

person's senses. This art form permeates the entire Church, even

through to the priests' vestments etc. There is a theology

here also. The frugality of the vestments, without any additions,

without an excess of imagery on them and a multitude of colours...

Our Church prefers frugality in all these things. But our job here

is to observe the hagiography and and remember that frugality,

which is expressed here with this staff and the Angel's outstretched

arm.

The Angel also has a stripe on his garment - we can see this stripe

on Christ's garments also - which states that as an officer, he has

received instructions. He has been given a power from a higher

authority. He is stating that an Angel is not independent. He does

not function independently. He does not function per the

measures of personal desires, but is obeisant to God. That

stripe-insignia denotes the authority given to him. With

Christ, the authority given to Him is also denoted by a band, but at

the same time, we can see Him - almost always - holding in his hands

a scroll. The Scriptures in the past were not in the form of books;

they were in the form of those rolled-up scrolls of papyrus.

Christ was given the authority by the Father, to do what He was to

do. In short, no-one is independent.

Other than that, angels are portrayed the way we have seen them. We

have seen them human in appearance, we have seen them with wings.

They are not a concoction of ours. We portray whatever we have seen,

in a theological manner. The troparia chants of our Church mention

them as "secondary lights". The primary light is God. Everyone else

- the saints and the angels - are secondary lights because they

obtain their light from God. No-one has their own light. Even the

halos depicted on the heads of saints are an expression of that

secondary light. It is God's light, which illuminates their whole

head.

You should remember that we always honour all the angels on Mondays.

Every time it is Monday, we honour the angels. Just as Sunday is the

day of the Resurrection. Monday is for the angels. Tuesdays are for

Saint John the Baptist. Wednesdays are for the Crucifixion and the

Holy Mother. Thursdays are for the Holy Apostles and always for

Saint Nicholas, in the status of a Hierarch. Fridays are again for

the Holy Mother and at the same time for the Cross. Saturdays are

for the reposed and Sundays are for the Resurrection. Of

course, these are in addition to the saints that are commemorated

each day. Thus, if you notice, all of the troparia hymns on

Mondays - if you open up the Book of Supplications called "Parakleteke"

- always include references to angels. Theological troparia on

angels can also be found in the Midnight services, and Sunday

mornings, when the triadic dogma of our Church is expressed, in

which angels participate with their ministering, as secondary

lights.

I am saying all this, so that you may acquire a broader experience,

as we do not have segmental arts. A hagiographer is born and

develops within the life of the Church. He has to see things more

broadly. A hagiographer who is not a churchgoer, who does not

partake of the mystery of the Church, will never be able to

undertake hagiography. Much less a hagiographer who doesn't know any

elementary theological things.

Let us now take a look at the Holy Mother. We can see that She

is seated. The Holy Mother or Christ can usually be portrayed

as seated. The seated position denotes certainty. Her

outstretched arm is a gesture of acceptance. It means "I accept".

We aren't dealing with comic strips here, where we need to insert

expressions and words. Acceptance is also denoted by a lowered

head. We can see a minimal, very slight bowing of the head, which,

together with the hand gesture, is a statement of acceptance. Thus,

wherever we see or want to express acceptance of an event, we

portray a bowed head. A minimal, tiny move of humility which

is not overly apparent; that is, not an explosive humility. That

would have also been a romantic or "deafening" element. An open palm

also denotes acceptance.

In He other hand the Holy Mother is holding another object. It is a

spindle for making yarn. This denotes something else that the Holy

Mother is - Who is more precious that the Cherubim and incomparably

more glorious than the Seraphim; Who resembles the angelic hosts and

is far more precious than all of them - but Who simultaneously

remains human and is preoccupied with human work. That is why

She is holding that spindle. No-one in the life of the Church is an

exclusively spiritual person. Given that people bear everything

carnal and a carnal nature - which is not a sin per se - they must

also perform human labours. Work. And you should remember that

ascetic theory in its entirety, and the neptic theory of Orthodoxy

are judged by alternation - that is, by the simultaneous application

of work and prayer. That is why the Holy Mother is holding a

spindle. And is seated.

I have already spoken of the three stars that are depicted on the

Holy Mother - one on Her head and the other two on each of Her

shoulders. The stars are 8-pointed; they each have 8 rays.

The triple star denotes that the Holy Mother is ever-virginal. She

was, is and forever will be a Virgin - before, during and after the

Birth. The 8-pointed star with its 8 rays denotes the mystery of

the "eighth day". The mystery of the eighth day is the mystery that

God had inaugurated with His plan of divine

providence (oekonomia)

in order to save mankind; because on the "seventh day", the last

"day" of Creation, we failed in that which God created us for. We

too by participating the way the Holy Mother does, are likewise

participating in the plan of divine

providence (oekonomia).

The Fathers of the Church have theologized about the Person of the

Holy Mother; this was during the third Ecumenical Synod. During the

Ecumenical Synod of Ephesus, where certain persons such as the

heretic Nestorius had maintained that the Holy Mother is not a

"Theo-tokos" (who had given birth to God), but a "Christo-tokos"

(who had given birth to Christ. You might ask: What is the

difference? The difference is huge. "Theotokos" is one

thing, and "Christotokos" is another. What does this difference

mean? Well, Nestorius had asserted the She was the "Christotokos"

- that She had given birth to Christ, and nothing more. According to

Nestorius, She was merely a pipeline, which Christ had merely passed

through. That is a theological error. How was Christ born?

What do we confess in the Creed? "....incarnated by the Holy Spirit

and Mary the Virgin, and become Man...". Two events are taking place

here. Just as the birth of a child requires the collaboration

of a man and a woman, here, the grace of the Holy Spirit is the

collaborator: "....incarnated by the Holy Spirit and Mary the

Virgin, and become Man...". What does the Holy Mother do? She

provides human (worldly) flesh to Christ. Therefore the Holy

Mother's participation is not simply the participation of a pipeline

that serves a situation. Christ does not merely pass through

Her, from inside, without the Holy Mother offering the human

magnitude. Christ assumes the human magnitudes thanks to the

Holy Mother; therefore, She is a Theo-tokos. It is God

Who is born, and made incarnate. The difference is huge. And a whole

Ecumenical Synod had been convened on this topic alone - if the Holy

Mother is a "Christo-tokos" or "Theo-tokos". And this theology

was tackled by very many of the major Fathers, such as Cyril of

Alexandria and other theologians, who had originally theologized on

the Person of our Holy Mother.

I will now return to the first icon of the Annunciation. There are

secondary elements in there, which can be presented chromatically

also. There is the throne. Or even that red cloth that is draped at

the top. We insert that draped cloth in other icons also -

usually in depictions of Magisterial feast-days, or in the

portrayals of Christ and the Holy Mother; that red cloth is a

statement of a joyous event. We could call it a

joyous-resurrectional event. However, it is only a secondary

element, in the sense that it may or may not be inserted in an icon.

You will not see it in every icon. It alternates, according to the

iconographer's choice. The theological elements however are

used exactly as they are. For example, the platform that the

Angel or the Theotokos is standing on is a secondary element. It is

very important to distinguish between the theological elements and

the secondary ones.

The colour of the Holy Mother's garment, Her external robe is dark

red, which is the colour that Orthodoxy regards as a deeply solemn

colour. Our Church never uses the colour black. It is highly

unfortunate when priests dress in black vestments - especially

during Great Lent - or place black covers atop the Holy Altar during

Lent. We do not have that absolute degree of sorrow. As

we shall also see from the shape of the mouth that is depicted, we

are speaking of that "joyous-sorrow". These are two elements

combined. We are never in absolute joy and absolute sorrow. Absolute

joy is a utopia, because we are living in a post-Fall state. And

absolute sorrow is a tragedy, because sorrow indicates that you have

lost everything, that there is no hope in Christ. The only

thing that we feel sorry for. We are sorry for our sins. It is what

Christ had said: "be angered, and do not sin". We need to be

angry over our sins only. We should not sin for any reason. And we

should only feel sorrow for our sins. During His moments of prayer

in the Garden of Gethsemane, Christ (according to Mark's Gospel) is

mentioned as being "sorrowful". Specifically, His words were: "My

soul is surrounded by sorrow, even unto death" («περίλυπος

εστιν η ψυχή μου έως θανάτου» - Matt.26:38). This does not

imply that Christ was disillusioned. You must notice the (Greek)

word used here. He is "sorrow-surrounded" (περίλυπος

peri-lypos); He is not sad; He is merely engulfed by

sorrow. Which means that sorrow is around ("peri") Him. It is the

sorrow of sin that is in action around Him, and that is why He is

surrounded by sorrow - sorrow for our sins. Our Church never

indulges in events of absolute sorrow or grief. Good Friday is

not a day of sorrow. This is an entirely mistaken approach. It is a

day of "joyous sorrow". We feel sorrow for one thing: for having

dared to crucify Christ. And at the same time, we feel joy, because

Christ was resurrected. That is why, when you go to church on

the morning of Good Friday - which is when the Vespers of Holy

Saturday are celebrated - you will see the priests are obliged to

wear white vestments. And even if they had worn black vestments

during the Lenten period, they must necessarily change them and wear

white, because that is when the mystery of Christ's descent into

Hades takes place, and at the moment that He is dead on the Cross,

that is also when death is conquered. We do not have events of

sorrow and grief; we have that "joyous sorrow", which is ministered

to, throughout our life. As I said, absolute joy is a utopia. It is

a fictitious psychological state that cannot do anything more than

make us get away from our confrontation of sorrow for our sins.

If you have something, you can ask me on the things I just told you.

I have said everything very briefly, but I wanted to mention every

aspect, so that you can gradually handle the theology of the icon.

Question:

Why is the Holy Mother seated in this icon of the Annunciation?

Reply:

I already mentioned the theology behind the seated pose. The Holy

Mother is not always depicted in a seated position in the icons of

the Annunciation. However, this example is very correct, because the

seated position that refers to Christ and the Holy Mother denotes

certainty. The seated position implies certainty - what is to ensue

is a certainty. The Holy Mother is certain about what She is doing.

She is accepting God's proposal. And She does it, without knowing

the facts analytically.

Question:

Why are secondary elements so sumptuous in some icons?

Reply:

Look. The are not sumptuous, because they merely highlight the

persons. For example, those platforms do not overwhelm the image;

they are subordinate to the image. A hagiographer has the freedom to

work the secondary elements. What he doesn't have, is the freedom to

tamper with the theology. The freedom for the hagiographer to

express himself remains a possibility, only in those secondary

elements. But in the primary ones (that pertain to theology) he does

not have that freedom. If he does change them, he may well fall into

heresy.

Question:

Why do monks and priests wear black garments?

Reply:

Liturgical use is one thing, and my personal use is another. Black,

for my personal use, expresses the remembrance of death. All monks

wear black. In the Divine Liturgy however, the priests wear white or

red vestments. That is because it is a liturgical event, where the

Grace of God is ministered to. This magnitude - the "dress code" -

has a special handling. You see, I live inside this world, inside

this life. I have to wear the shoes that all of you wear. Isn't that

so? I am living human things. With black, I have a remembrance of

death. But when I enter a church service, no matter what happens,

whatever I may do, the black is overtaken by certain other garments

that I put on, which are not black. Black is a reminder of

death to me. But the Divine Liturgy is a community event, a communal

event. The remembrance of death is a personal event for me; it

is not a liturgical event, where the joyous-resurrectional event of

our Christ's grace is celebrated. And the white vestments that the

Russians wear - certain white stoles, robes or white vestments - are

an incorrect tradition which was brought over by a delusion that

came to Rome through the so-called Donation of Constantine. This was

a lie that they had circulated somewhere in Rome, that (supposedly)

Constantine the Great had made a donation to Rome before his death,

granting it to be the first church. There is no such thing. Anyway,

along with that donation of his, he had also gifted a white vestment

for them to wear etc.... and thus, an entire myth was conveyed to

Moscow. There are two lies, on which certain elements of

theology of the Vaticanian "church" were based; one was the

"Donation of Constantine" and the other was the "Pseudo-Isidorian

clauses" which I have not enough time to analyze. They are not of

concern at this time.

Question:

Why is the event of the Annunciation depicted in an external

setting?

Reply:

In hagiography, we never depict an interior space (as for example

the interior of a temple). All events are external; there is no

internal space. Nothing is closed within walls in hagiography.

Everything exists outside. An event may take place somewhere inside,

internally, but a house will be depicted as an outdoor setting. In

hagiography we never close ourselves in. Everything is an exit.

There is no interior. Even if a liturgy is depicted, you will never

see where there is a closed temple, you will never see any walls.

Because the Liturgy itself is an exit from the things of this world.

Woe betide, if the Church were to be closed in, or performed a

Liturgy for enjoyment, or to acquire solemnity, and nothing more.

The Liturgy is an exit. And we participate in the Liturgy, so that

we might acquire the potential to make an exit, towards the world,

towards God and the others. There is never any closed space in

hagiography. Never. Even when it refers to doubting Thomas, "with

the doors closed", where "the disciples were gathered for fear of

the Judeans", the Apostles are depicted in an open space. Even

though the Holy Bible itself states "with the doors closed",

nevertheless, hagiography portrays them as standing outside.

The same thing can be observed in the icon of the Pentecost - even

though the Pentecost happened inside a loft.

That is the theology of our icon. There are no closed spaces. Just

as there is no person who remains closed within himself. The Church

is always a constant exit.

Question:

How are lips depicted in hagiography?

Reply:

I will mention only two points about the lips. One is a local point,

the other is theological. The others you will see, when you study

the lips further. A very important feature of the face, like

the eyes and the nose, are also of course the lips. With the

lips, we often express joy, sorrow, as well as the "joyous sorrow"

that we mentioned earlier. First of all, as a local point on the

icon you can see the "E" point. That is, the lower part of the

bottom lip is located at the center of the third section of the face

of saints. We recall how the head is divided into four equal

sections. And the face in three equal sections. This I believe you

all know, from our previous analyses: that the head is four noses

long and the face three noses long. The last section, the lower part

of the face, the chin area, is also where the lips are found.

It is at the center of this last section that the "E" point is. In

other words, the lips will always end at the last point of the mid

section of the last section. If you observe the icon that I

gave you, you can see in the third section of the face, below, right

in the middle is the "E" point, and after that are the lips, at the

top. That is, the lips are entirely within the topmost space of the

last section of the face. What is of great interest to us, is

how to express the lips. We have learnt from every other form of

painting that we have sad lips or happy lips. Just bring to

mind for example a person who is sad, and another, happy one. That

is what we have been taught. But in hagiography, both these

elements are abolished. Because as I mentioned earlier, we do not

have absolute joy, or absolute sorrow. We have that "joyous sorrow".

However, we also do not have a straight line. A straight line would

have denoted a person who has no feelings whatsoever, and as such,

no emotions. A "frozen" person. We have "joyous sorrow". Or,

in another expression of the Church Fathers: a joy-inducing

mourning. Two expressions: Joyous sorrow or joy-inducing

mourning. What we want is to combine the presence of a joy-inducing

mourning and a joyous sorrow, in the expression of the lip opening.

That is where we express it. That is how we were also taught in

drawing. The opening between the lips is what expresses joy or

sorrow. And we have only Joyous sorrow or joy-inducing mourning,

therefore we must simultaneously combine the lines that express joy

and the lines that express sorrow. That is why we draw a line of

sorrow and a line of joy, simultaneously. Sorrow - joy,

alternating. That is the lip line of joyous sorrow; not fleshy lips.