We

shall continue with our lessons on the theology of icons. And of

course it will be at that same level as the one that we are tackling

- one-sided. That is why we are doing an analysis of the

theology of the icon. Icons also have other key features

inside them, so that we can approach them beyond the theological

approach. One very important approach that pertains to the balance

of the image itself is the geometry of the icon. In future lessons

we will begin to also notice the balance of the image. Balance

of image means that unbeknownst to him, the artist (which is why he

is an artist; it is an instinct) gives the image a pure geometric

balance. That is, if I select a central point in the icon -

say, for example, the head of the Holy Mother - and draw triangles

that lead to Her feet, I will notice those pure balances.

Or, if I observe any icon of the Holy Trinity - where the three

angels are seated at a table - and I draw an imaginary circle around

the three of them, I will be able to discern that the exact centre

of that circle is on the table - and that the Angels are clearly

"included", along with the table (see example below).

This is a balance that is found in the artistry that belongs to

superior craftsmen, because this art has a latent geometrical

balance. Recently, at a university in America where they study

Byzantine hagiography, a special study was performed on icons, with

the use of computers. They stored images of the icons in a

computer, they studied them, and they discovered actual geometrical

balances in them. Even if we ourselves are not knowledgeable and are

not as great craftsmen, we are nevertheless helped, by becoming

familiar with these balances. This is the visible theology of art

and these are the visible balances that we are analyzing.

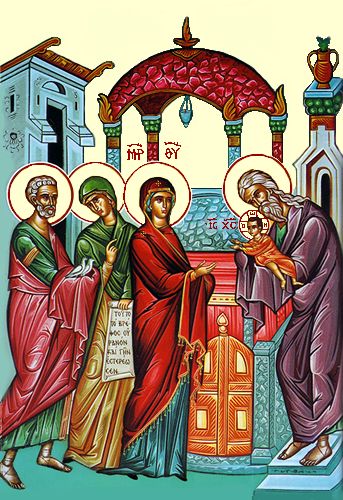

Let us observe the icon of the Presentation of the Lord - the

reception of the Lord - on the fortieth day after His Birth, at the

Temple, the only existing Temple at the time, the Temple of the

Jews, the Temple of Solomon. The religion of the Jews had only

one Temple. Up until that Temple was built by Solomon, they had no

Temple at all; they merely had a tent - the tabernacle - from the

time of Moses; the

Tabernacle of the Witness, in which they kept all the sanctified

objects. In it, they had placed the tablets of the Law, the Mannah,

the Staff - whatever they had as evidence. And they would

carry everything on their backs, saying that this is the Tabernacle

of the Witness, where they would say their prayers. When

Israel finally settled down in its own land and acquired a kingdom

(Solomon was the third major king), that was when they built the

Temple of Solomon. And it was the one and only Temple where the

rituals and the sacrifices were performed. Without the existence of

a temple, they were unable to do anything. And in fact, when the

temple was destroyed later on, or when the Israelites left their

land after they were made captives, all the while that they were in

exile and their temple destroyed, no rituals whatsoever could take

place. Only prayers were said. The Jews underwent two

captivities - the Babylonian captivity and the captivity by the

Assyrians. In fact, the destruction of the Temple of Solomon

in 67 A.D. had been foretold by Christ, and He had said that not a

stone would be left standing in that temple. In 67 A.D., when

Vespasian's armies stormed the city, they trashed everything.

Jerusalem was under siege for three years, and the Jews endured for

three years, however they ended up in tragic circumstances. First,

they ate all the animals in the city - even the cats and the rats,

then they ate their own children in order to defend the sacred city.

The city finally fell, and they dispersed. This was the historical

diaspora (dispersion) of Israel to all the parts of the world, up to

the year 1048 when they returned and acquired the State of Israel.

From that time and up until this day when they still don't have a

Temple (even though they have a State, but because they don't have a

Temple), they do not perform any rituals. Not a single ritual.

Everything else that they do is merely an expression of a synaxis, a

congregating inside the synagogue to be reminded of what used to be

performed inside the Temple. That is why - until this day - the

people of Israel have such a burning desire to

rebuild the

Temple of Solomon. But the Temple cannot be built. All it has

now is the Wailing Wall. Because today, atop the area of Solomon's

Temple, there is the Mosque of Omar - an Islami mosque, which at

present may operate as a museum, but it nevertheless deprives them

of the possibility to perform worship there. And that is a grand

expectation for all the people of Israel. The expectation of

Israel is for that area to be opened, as a Temple.

In the icon of the Presentation, we find ourselves in that single

place where worship was performed. And it was at a time when worship

did take place. Christ came along at the time when the Temple of

Solomon was in existence. So, we are at that Temple, which, from its

exterior appearance as we see it, has the form of an Orthodox

Christian temple, because as you can see, there is the royal portal,

the way it used to be, up until the 8th or 9th century. We have the

Holy Altar and we have the Kivorion (canopy) over it - or the "sky",

as it used to be called - which is an element that one finds in

Orthodox architecture. "Kivorion" is that which covers. And if you

go to any proto-Christian churches or churches up to the 4th or 5th

century, you will find kivoria. If you go to the church of Panaghia

Ekatontapyliani (= of 100-portals) on Paros Island and pay your

respects there, you will see its Holy Altar also has a kivorion

standing over it (photo below).

All the old temples have a kivorion; therefore, this temple here -

judging by its appearance - reminds us of a Christian temple. This

is absolutely correct, because the Temple of Solomon was destroyed

and has been transformed into a Christian temple. In other words,

the temple simply changes its method of sacrifice. There used to be

physical animal sacrifices, but now there are logical sacrifices.

Christ is sacrificed, and we perform a logical sacrifice:

"...a heart that is crushed and humbled" is what God wants. "I want

charity, not sacrifice" - a heart that is contrite... Therefore,

this temple here, in the icon of the Presentation, is rightly

depicted hagiographically as an Orthodox temple, even though when

Christ had entered it, it was the Temple of Solomon at the time.

But here we have a transformation, precisely because Christ had

entered it. And He transforms everything inside an Orthodox temple.

You must pay attention to these metaphors; we now go beyond the

historicity of events and embark on the interpretation of the events

depicted. I have mentioned this at other times - that we do

not deal with historical analysis. Nor is it our purpose to present

a history by way of pictorial designs. In hagiography, we

theologize on History, which is why we very aptly do not depict the

actual Temple of Solomon the way that we imagined or knew

approximately what it looked like. We are now touching on elements

of the Christian temple, which has preserved the old elements, but

merely gives them a different ethos: we no longer have an altar for

sacrificing animals; instead, we have a sacrificial altar on which

Christ will be sacrificed - the Holy Altar.

I will say a few more words on the substructure of this icon, which

is its architecture. I have already mentioned the royal

portal. Indeed, from the 1st to the 9th century, the royal portal of

the sanctum was positioned lower. After the 9th to 10th century, the

royal portal was raised, to form the present, all-familiar templon

(iconostasis). And this is very appropriate, as our Church

develops its architecture according to the measures of Her theology.

And theology is ever evolving, ever incremental. Incremental

does not imply an abolishing of previous things. It is a

multiplying. Because, for as long as we are living within the

History of the world, the Grace of the Holy Spirit comes along and

sheds light among Christians. And we thus increase our theology. In

other words, we have an incremental theology. This does not mean we

have abolished Saint John the Chrysostom and Saint Gregory the

Theologian, who lived in the 4th to 5th centuries. Everything that

they said was extremely significant and huge. Then, later on,

the Holy Fathers come along and add even more to them. This is

along the lines of what Christ had said to His disciples: "when the

Holy Spirit - the Comforter - comes, He shall lead you to all the

truth". Someone who does not understand what this means - for

example a Protestant - will wonder: "Does that mean Christ had not

told all the truth?" Of course Christ said all the truth! And

there is nothing that we could add to it. However, by the Grace of

the Holy Spirit, and according to the measure of our intellectual

and logical potential, we strive to analyze that truth in more

detail. This is why we notice the Fathers analyzing the same

verse in even more depth. Even I for example may read a text,

then examine a hermeneutic approach to it, then I read the text

again, and then approach more hermeneutic approaches, and in this

way, I can see the same text in even more depth than before.

Because when a text is a divine and revealed one, it always has a

greater depth to it. This is what we call the incrementing of

our theology. That is why the templon (iconostasis) was eventually

raised - according to the measures of our incremented theology.

What kind of incremental theology did we have? Well, after the 10th

century we had a situation which had created those terrible

hesychast quarrels that began in Thessaloniki at the time of Saint

Gregory Palamas, when the huge issue of how we approach God was

posed. Are we near Him or far away from Him? Do we see Him or

don't we see Him? Well, God is both visible and invisible. He

is approachable and inapproachable. He is visible, to the degree

that we can see Him, according to the potential of our nature - as

for example with the Sun. To the degree that our eyes can

tolerate it and we do not get burnt, we can look at the Sun.

To the degree that our eyes will be burnt, we cannot see the Sun.

In the same sense, we can and we cannot see God. We can see

only whatever our human nature can bear.

Whatever we cannot see of God (which means our human nature

cannot bear it), we call it the Essence

of God.

Whatever we can see of God (which means our human nature can bear it), we call it the

Energies

of God.

Be

careful here: when I say "Energies", it is a totally different thing

to -let's say- electric energy. This is God Himself. This is a

theological term. When I say "an Energy of God", I mean God Himself,

but only to the degree that I can "see" Him. And when I say "His

Essence", I also mean God - the same God - to the degree that I

can't "see" Him. Thus, we have a theology of the Essence and of the

Energies - and specifically of the uncreated energies of God

(in order to differentiate them from any other energy, such as

electromagnetic, or electric etc.). The only uncreated

energy is God. So, if we have Uncreated Energies, then that is God.

This is a terminology that also came to permeate the architecture of

a church, where the sanctum was separated from the main temple, by

means of a templon (iconostasis). There the sanctum

symbolically denotes the Essence of God, while the space beyond the

sanctum denotes the Energies of God. The approachable and the

unapproachable. What I can see and what I cannot see. They are

symbolisms. So we see with the incrementing of our theology,

it takes on a finalized form in the 13th - 14th century with Saint

Gregory Palamas, hence we observe the raising of the templon higher

up. In other words, it is not an architectural whim; it is theology

that guides the church towards developments.

You see, churches initially were linear. Just like a corridor. The

so-called "basilicas". You would enter through the door and ahead of

you would be the sanctum. Quite correct. You enter God's space and

you move forward to find God. This is a linear, horizontal movement.

However, when theology was incremented on the issue of Triadology

and specifically on the issue of Christ's extreme condescension

(especially at the 4th Ecumenical Council in 451 A.D.) when Christ

came along and became incarnate and assumed the entire world, we

also wished to express Christ's descent into Hades. Christ descends.

So we add the dome. This is Christ's embrace which assumes the

world, which descends towards us, and we ascend towards Him. There

is here the course towards Christ, and at the same time Christ's

embrace. You see, in the year 451 A.D., there existed a

Christological theology. The church of Hagia Sophia is built and the

first dome in history is constructed around 532 to 538 A.D., which

was the result of this theology - a theological action by the

emperor Justinian. And the Church honours Justinian as a saint

as well; that is, he had a divine conception when he embarked on

building this temple.

Now let us take a look at the Holy Altar. Atop the Holy Altar

we always have the Gospel. Whereas in the temple of Solomon there

was no Gospel; there was only the place where the sacrifices were

performed. The Gospel is the Word of God. We always place it

on top of the Holy Altar, except in one instance. Half way through

the Divine Liturgy, when the procession of the Great Entrance takes

place and we bring the precious gifts to be sanctified, we remove

the Gospel from its place and put it aside, and at the center we now

place the bread and the wine which are to become the Body and the

Blood of Christ. This is the only moment when the Word of God is not

atop the Holy Altar. This too is absolutely correct. Christ, Who is

the Word-Logos, first comes and is proclaimed, then He is

sacrificed. The first procession (Entrance) is performed with

the Gospel. We read the Gospel. All these things are interlinked and

comprise a theology. The Entrance of the Gospel is performed during

the Divine Liturgy, which signifies that the Word-Logos will be

proclaimed. Then we have the Great Entrance of the Precious Gifts,

which signifies that the Word-Logos will be sacrificed. So we have

the liturgy of the Logos and the liturgy of the Sacrifice, where the

Precious Gifts arrive and the Gospel is put aside.

Now look at this other, liturgical movement:

Old Simeon comes along, he holds Christ in his hands on the fortieth

day after His Birth, and receives Him like an offering that will be

placed on the Holy Altar to be sacrificed. This is a purely

liturgical scene. Do you see? The elderly Simeon is a priest,

and he takes the infant Jesus as though he is taking an offering

from the hands of the Holy Mother, in order to sacrifice the Christ

on the Holy Altar - exactly the way that a priest always does.

So, this scene is a statement that Christ came, to be sacrificed.

You cannot portray this image differently. When priests

officiate in church, they wear an overgarment - the

phelonion - with

which they cover their hands. This signifies that their hands are

not theirs, because they are lending them to God. The elderly Simeon

therefore receives Christ with his hands hidden, because he has

nothing of his own to say. He will be doing whatever God tells him.

And he will be ministering to Christ. And in hagiography, the

depiction of an inclined head denotes the acceptance of an event.

The picture speaks for itself with the postures that are depicted.

Here we have the elderly Simeon, who was waiting at the temple for

the Christ to come, so that he could say "Now release Your servant o

Lord - according to your word - in peace."

In the icon we have the Holy Mother, the way she

is depicted hagiographically, with the three 8-pointed stars. You

will note that the Holy Mother has Her one hand uncovered and the

other one covered. The covered hand denotes the hand that is

ministering; the open hand is the hand of acceptance - not merely

the hand that is offering Christ, but the hand that is par

excellence acknowledging acceptance of the event. In other words,

She is offering Him to be sacrificed, and She is accepting that

event; because that is the sole reason Christ came to this world :

to sacrifice Himself.

Behind Her stands the prophetess Anna, daughter

of Fanuel, the way she is described by

Luke the Evangelist who knew all the events of the Holy Mother's

life because he lived close to Her and had learnt of these events

from Her mouth. Thus we have Fanuel's daughter who is recorded

as a prophetess and who was also expecting to see the Christ, which

is why she is depicted in hagiography as pointing towards Christ

with her finger. Prophets are indicators. And the prophetess Anna

also has her one arm inclined.

The last figure depicted behind Her is Joseph the

Betrothed. He is once again depicted as a deacon ministering to a

mystery, just as he was ministering in the Icon of the Nativity.

In hagiography we never depict a "holy family". If it were an actual

family, Joseph would have been near Her - next to Her. But here he

is behind Her. Everyone is ministering to Christ. There is no family

per se; not the usual kind. Joseph is once again a deacon

ministering to a mystery and he

is holding two doves in his hands. This detail was a Jewish

tradition, when people would go to the temple bringing their

offerings. A poor family would offer grain or produce of the

earth, in other words cereals. A family could also offer

animals for sacrificing, while others would offer two young doves.

The two doves here represent the Old and the New Testaments.

The "sky" (the kivorion) as you can see is also an inclined form -

it is like a dome that "condescends" earthwards, in order to embrace

the world. And, once again, the backdrop is hagiographically

depicted as an outdoor scene, even though the event is taking place

inside the temple. We never have a closed space in Orthodox

hagiography. All scenes are in the open and we are on an

exiting course - we always exit.

I will now go back to the subject of ministering

to the Logos and to the Sacrifice: In the Orthodox Church, it

is never permitted for the sermon (the kerygma) to take place at any

other point during the Divine Liturgy, except only after the Gospel

reading and interpretation. After the interpretation of the

Gospel, it is time for the Sacrifice. When Christ was being

sacrificed, He was not speaking. That is why it is so inappropriate,

anti-liturgical and non-Orthodox for the priest to preach the sermon

at any other moment. Was the Gospel proclaimed? Then the sermon

comes immediately after, and then, nothing else. An illogical

thing that sometimes occurs today is that the priest comes forth to

give the sermon, a little before it is nearing the time to impart

Holy Communion. That is entirely illogical. What are the

reasons for the sermon? For people to hear it. Why should they hear

it? After all, they came to partake of the Liturgy, to

experience the Church of Christ. That is why the sermon must be

given earlier. Because later on, during the phase of Holy Communion,

the people are fewer... Never mind... We want to perform the

Liturgy, we don't want to make any speeches....

If we are ignorant of theology, then

neither will the Liturgy be performed correctly, nor will

hagiography.

Question:

How do we depict the ear?

Reply:

We are already finishing with the parts of the

face. The last part of the face that we haven't analyzed at all is

the ear. If the whole head is a measure, then the whole body

is comprised of eight heads lengthwise. Always remember that. A

person's entire body is comprised of eight heads.

Something about

the word ear (Greek: otion, pron. aw-teeon).

When you encounter the root word "otion", you can

recognize it in other, related words. Quite often you will encounter

the word "hearken" in the Holy Bible. The word "hearken"

contains the particle "hear", just as the equivalent Greek verb in

the Holy Bible: "εν-ωτίζου" (pron. en-awteezou)

signifies "listen well" ("lend me your ear"). In fact the

prophet Moses uses this expression when he is concerned that the

Israelites will not pay attention to him - he says to them: "hearken

to me, o heaven and listen, earth". In other words, he is saying

that he hopes the inanimate sky and the earth will listen to him, in

the hope that they (the Israelites) will be moved and listen to him.

Now the Greek word

otion is written with omega as its first letter (ωτίον).

According to the ancient Greek language, the

omega is in fact two "o"s joined together. The letter "o" has always

represented a circumference - an enclosure: O. It is a

visual thing. A boundary, a space that you define, is an "O".

It is a border, see? The word "border" contains an "o"

within it. It is an expressive medium - a geographical one,

describing a specific area. If that area is a large one, it is

denoted (in Greek) by two "o"s placed next to each other. That is

what is known as the "o"-mega (the large "o"). Thus, the Greek

word for ear - "otion" - begins with the

letter omega, because it is an expressive magnitude of mankind that

extends to a great distance. Similarly the (ancient Greek)

word for eyes (ώπα - pron. aw-pah)

likewise begins with omega. Whatever sensation reaches a long

distance is omega. Otion and Opa. In this sense, the

otion - the ear - in hagiography expresses the potential to hear

something very distant, which implies the messages from God.

When we depict the ear in hagiography as relatively exposed and

relatively hidden, the ear is partly visible. The ear has to

exist in the depiction, but only in the sense of an ear's spiritual

presence - the kind that perceives in a deeply spiritual manner

whatever the ear hears about God. Therefore that is how you should

approach the ear. You must not say "oh well, it doesn't matter -

after all, the saint had a lot of hair and his ears can't be seen"

etc... a small expressive portion of the ear must always be

depicted, thus showing that the sense of hearing is also present,

and is cultivated like all the other senses.