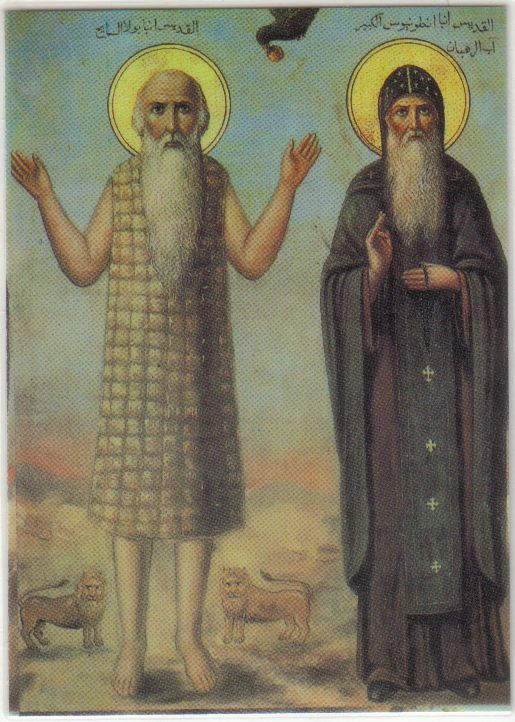

p. 417: “Often the saint was shown in the

company of his friend St Paul the Hermit: while St

Anthony was held by the Copts* to be the first monk,

St Paul was said to be the first hermit. When the

two were shown together they were always accompanied

by a raven that, according to St Jerome’s version of

the legend, diligently brought a loaf of bread every

day to their cave. In some icons the two men were

also accompanied by a pair of lions (see

icon below), again a

reference to St Jerome’s “Life of St Paul the

First Hermit” which tells how the lions helped

St Anthony bury his friend:

Even as St Anthony pondered how he was to

bury his friend, two lions came coursing,

their manes flying, from the inner desert

and made towards him. At the sight of them,

he was at first in dread: then turning his

mind to God, he waited undismayed, as though

he looked on doves. They came straight to

the body of the Holy Paul, and halted by it

wagging their tails, then crouched

themselves at his feet, roaring mightily;

and Anthony knew well they were lamenting

him, as best they could. Then, going a

little way off, they began to scratch up the

ground with their paws, vying with each

other to throw up the sand, till they had

dug a grave roomy enough for a man ...

Coptic

icon of Holy Paul the Hermit with Saint Anthony

The reason for my particular interest in the icons

of St Anthony was that during the Dark Ages the

saint was also a favourite subject for the Pictish

artists of my native Scotland, as well as for those

across the sea in Ireland. The Celtic monks of both

countries consciously looked on St Anthony as their

ideal and their prototype, and the proudest boast of

Celtic monasticism was that, in the words of the

seventh-century Antiphonary of the Irish monastery

of Bangor:

This house full of delight

Is built on the rock

And indeed the true vine

Transplanted out of Egypt.

Moreover, the Egyptian ancestry of the Celtic Church

was acknowledged by contemporaries: in a letter to

Charlemagne, the English scholar-monk Alcuin

described the Celtic Culdees as ‘pueri

egyptiaci’, the children of the Egyptians.

Whether this implied direct contact between Coptic

Egypt and Celtic Ireland and Scotland is a matter of

scholarly debate. Common sense suggests that it is

unlikely, yet a growing body of scholars think that

that is exactly what Alcuin may have meant.

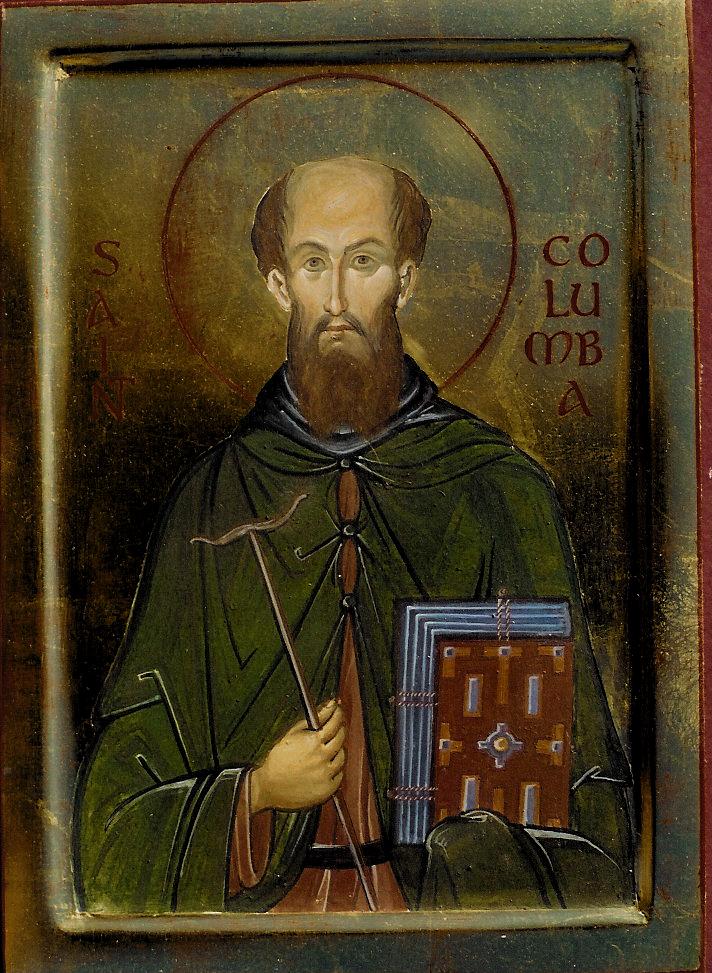

There are an extraordinary number of otherwise

inexplicable similarities between the Celtic and

Coptic Churches which were shared by no other

Western Churches. In both, the bishops wore crowns

rather than mitres and held

T-shaped Tau crosses

rather than crooks or crosiers (compare

icons below).

Saint Antony (Egypt)

Saint Columba (Scotland)

In both, the hand-bell played a very prominent place in ritual, so

much so that in early Irish sculpture clerics are

distinguished form lay persons by placing a

clochette in their hand. The same device performs a

similar function on Coptic stele – yet bells of any

sort are quite unknown in the dominant Greek or

Latin Churches until the tenth century at the

earliest.

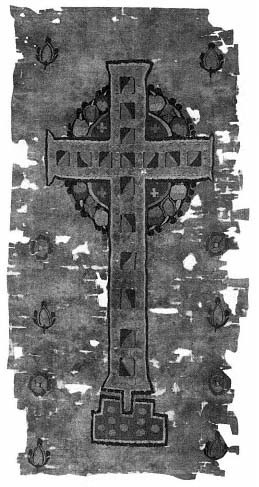

Stranger still, the Celtic wheel cross,

the most common symbol of Celtic Christianity, has

recently been shown to have been a Coptic invention,

depicted on a Coptic burial pall (see

image below) of the fifth

century, three centuries before the design first

appears in Scotland and Ireland.

Coptic burial pall, fifth to seventh century.

138.4 by 68.9 cm. The linen and wool fabric

is embroidered with a developed ring cross,

a design that became common on Irish cross

slabs and high crosses in the eighth and ninth

centuries. The vertical shaft terminates in a

tongue that rests in a groove in the base, a joint

characteristic of timber architecture but not used

in stone construction.

Photograph courtesy The Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

Certainly there is a growing body of evidence to

suggest that contact between the Mediterranean and

the Celtic fringe was possible. Egyptian pottery –

perhaps originally containing wine or olive oil –

has been found during excavations at Tintagel Castle

in Cornwall, the mythical birthplace of King

Arthur. The Irish Litany of Saints remembers

‘the

seven monks of Egypt (who lived) in Disert Uilaig”

on the west coast of Ireland. But the fullest

account of direct contact is given by none other

than Sophronius himself. In his “Life of

John the Almsgiver” (the saintly Patriarch with whom

he and Moschos fled Alexandria in 614 A.D.),

Sophronius tells the story of an accidental voyage

to Britain – more specifically, in all likelihood,

to Cornwall – undertaken by a bankrupt young

Alexandrian aristocrat to whom the Patriarch has

lent money:

“We sailed for twenty days and nights

(reported the man on his return) and owing to a

violent wind we were unable to tell in what

direction we were going either by the stars or

by the coast. But the only thing we knew was

that the steersman saw (an apparition of) the

Patriarch (John the Almsgiver) by his side,

holding his tiller and saying to him: ‘Fear

not! You are sailing quite right.’ Then, after

the twentieth day, we caught sight of the

islands of Britain, and when we had landed we

found a famine raging there. Accordingly, when

we told the chief man of the town that we were

laden with corn, he said, ‘God has brought you

at the right moment. Choose as you wish either

one “nomisma” for each bushel or a return

freight of tin.’ And we chose half of each.

Then we set sail again and joyfully made once

more for Alexandria, putting in on our way at

Pentapolis (in modern Libya).

p.420:

“..As I stood outside the church, Fr. Dioscuros came

over and introduced me to the Abbot. As we chatted,

I happened to mention how St Anthony had once been a

highly revered and much sculpted figure in my home

country. Surprised, the Abbot questioned me closely

about the Pictish images of his patron saint, and I

described to him the scene shown on a particularly

beautiful seventh-century Pictish stone from

St Vigeans (near Dundee) which illustrates the scene in

St Jerome’s

Life of St Paul the First Hermit

where the two saints meet for the first time. They

eat together but cannot agree which of them should

break the bread. Each defers to the other, until

finally they ‘agreed that each should take hold

of the loaf and pull towards himself, and let each

take what remained in his hands’.

In the Pictish version of the scene, the two saints

are shown in profile as they sit in high –backed

chairs facing each other, with one hand each

stretched out to hold a round loaf. It was a very

different image, I said, from any I had seen in the

monastery, all of which showed St Anthony standing

full-frontal, staring into the eyes of the onlooker,

in the classic Byzantine manner.

‘You are wrong,’ said the Abbot, smiling

enigmatically. ‘We have your image as well.

Come, I will show you.’

...I looked where he was pointing. There, under the

outstretched arm of the saint, a much smaller scene

had been painted. Two figures, immediately

recognisable as Paul and Antony, sat facing each

other in a cave under a hill, on top of which grew a

palm tree. Both figures had one arm outstretched to

grasp a round loaf of bread with a line down its

centre. It was exactly the image sculpted by the

unknown Pictish artists in seventh-century Scotland.

p. 422: The only conceivable explanation of

the similarity of the two scenes – one in Scotland,

one in Egypt, whole continents apart – is the icon

in the library must be a late copy of a much older

Coptic original, an earlier version of which had

somehow made its way from Egypt to Dark Age

Perthshire, either by trade**, pilgrimage or in the

hands of wandering Coptic monks.

======================================

Notes

*

A Copt is a native

Egyptian Christian. Copts are the direct descendants

of the Ancient Egyptians. The Coptic (antichalcedonian)

Church is the portion of the Church of Alexandria

which broke away from the other Orthodox churches in

the wake of the Fourth Ecumenical Council in

Chalcedon in 451. Sharing a common heritage

previously with the Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Church

of Alexandria, it traces its origins to the Apostle

Mark. The word "Coptic" was originally used to refer

to Egyptians in general , but it has undergone a

semantic shift over the centuries to mean more

specifically "Egyptian Christian".

**OODE Note:

Cornish tin has also been

identified in Mycenaean bronze;

Britain has not been as isolated from the east in

ancient times as is popularly held. [With

thanks for this information to an Orthodox Celt,

J.D.C.]

======================================

(From a review of the book)

In

587 A.D., two monks set off on an

extraordinary journey that would take them in an arc

across the entire Byzantine world, from the shores

of the Bosphorus to the sand dunes of Egypt. On the

way John Moschos and his pupil Sophronius the

Sophist stayed in caves, monasteries, and remote

hermitages, collecting the wisdom of the stylites

and the desert fathers before their fragile world

finally shattered under the great eruption of Islam.

More than a thousand years later, using Moschos's

writings as his guide, William Dalrymple sets off to

retrace their footsteps and composes "an evensong

for a dying civilization"

======================================

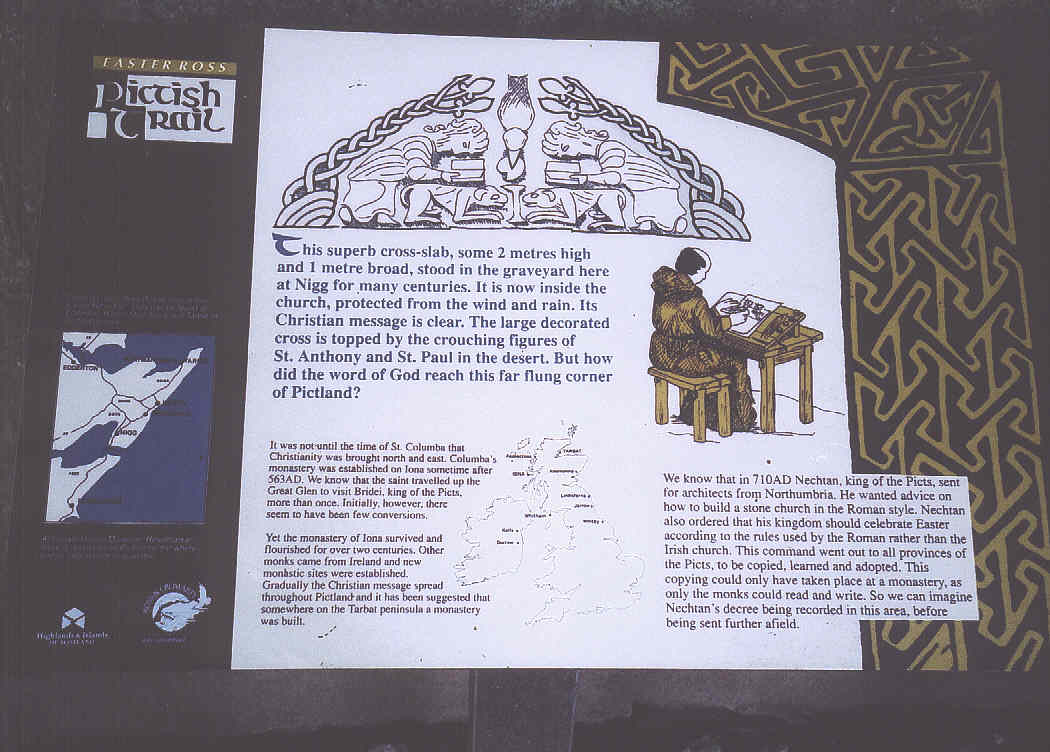

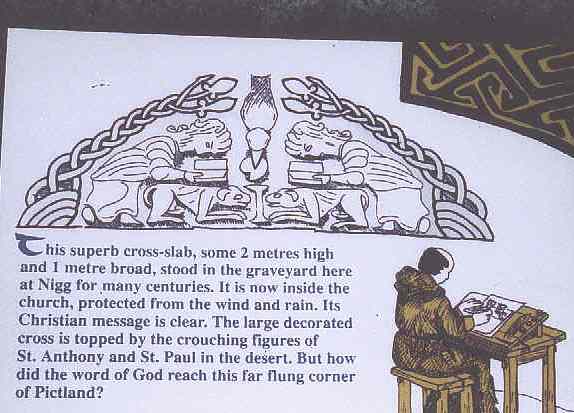

ANCIENT CHRISTIAN MONUMENTS IN SCOTLAND DEPICTING

EGYPTIAN SAINTS

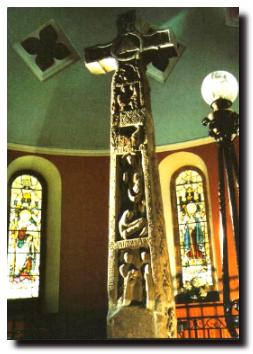

1. THE

PICTISH NIGG MONUMENT

The Pictish Nigg

Monument, Scotland (above) and

explanatory notice regarding the

two saints with

raven and 2 lions engraved on it (below).

detail ->

detail ->

==================================================================

2. THE RUTHWELL

CROSS

The

Ruthwell Cross is one of the oldest Preaching

Crosses in Europe, and was first raised on the

Solway towards the end of the 7th century. It is

thought to have been created by monks of the

Columban (or Scotic) Church, as a protest

against the Church of Rome. The Roman Church had

sought to achieve supremacy in England by

expelling the evangelical Church of Iona from

Northumbria in the North of England, an area

geographically close to the far south-west of

Scotland where the cross was sited.

The

cross is eighteen feet high, decorated with

sacred carvings depicting scenes from the New

Testament, and with ancient Runic letters. It

was probably created in 664AD, after the Synod

of Whitby. At that meeting of church-men, the

presbyter

Colman - Bishop of Lindisfarne, found it

impossible to stand alone against the united

Roman Bishops, led by Wilfrid, all of whom were

committed to Roman supremacy. As Colman and his

followers made their journey homewards, they

raised a Preaching Cross at Ruthwell. In a

sparsely populated land with few church

buildings it was probably one of a series raised

throughout Scotland. It signified the

consecrated ground on which the Worship of God

could be conducted, and where the Sacraments

could be administered.

Detail

at the base of Cross - Hermit Paul and Saint

Anthony breaking bread in the desert, as told by

the Latin inscription : SANCTVS PAVLVS ET

ANTONIVS DVO EREMITAE FREGERVNT PANEM IN DESERTO

=====================================================

3. SAINT

VIGEANS PICTISH STONES - SCOTLAND

Detail of

Hermit Paul and Saint Anthony breaking a round loaf

of bread