1. How Did Orthodoxy Reach Ireland?

How did Orthodox Christianity come to this small

green island off the shores of the European

continent in the uttermost West? Unknown to many,

Christianity in Ireland does have an Apostolic

foundation, through the Apostles James and John,

although the Apostles themselves never actually

visited there.

Monastic centres

in Ireland

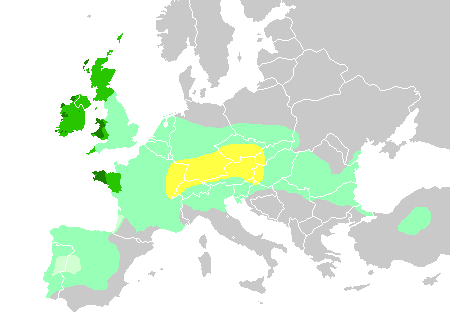

The Irish people were the westernmost extension of

the vast Celtic civilization—whose people called

themselves the Gauls—which stretched from southern

Russia through Europe and eventually into the

British Isles. (map below) The vastness of Celtic/Gallic

civilization is evident in the names used to

designate countries within its entire territory: the

land of Galatia in Asia Minor, Gaul (France),

Galicia (northwest Spain), and the land of

the Gaels (Ireland). The Celtic peoples (like

the Jews) kept in very close contact with their

kinfolk across the Eurasian continent.

Diachronic distribution of Celtic

peoples:

core Hallstatt territory, by the

sixth century BC maximal

Celtic expansion, by the third

century BC

Lusitanian

area of Iberia where Celtic presence is uncertain

the

"six

Celtic nations" which retained

significant numbers of

Celtic

speakers into the Early Modern period

areas

where Celtic languages remain widely

spoken today

When Christianity was

first being spread by the Apostles, those Celts who

heard their preaching and accepted it (seeing it as

the completion of the best parts of their ancient

traditions and beliefs) immediately told their

relatives, traveling by sea and land along routes

their ancestors had followed since before 1000 B.C.

The two Apostles whose teachings had the greatest

influence upon the Celtic peoples were the brothers

James and John, the sons of Zebedee. After Pentecost,

James first preached the Gospel to the dispersed

Israelites in Sardinia (an island in the

Mediterranean Sea off the east coast of Spain, which

was used as a penal colony). From there he went on

to the Spanish mainland and traveled throughout the

northern part of Spain along the river Ebro, where

his message was eagerly heard by the Celtic/Iberian

peoples, especially those in Galicia. This area

continued to be a portal to Ireland for many

centuries, especially for the transmission of the

Good News.

John preached throughout the whole territory of Asia

Minor (modern-day Turkey), and the many peoples

living there accepted Christianity, including the

Celtic peoples known as the Galatians (in Cappadocia).

These people also communicated with their relatives

throughout the Greco/Roman world of the time,

especially those in Gaul. By the middle of the 2nd

century the Celtic Christians in Gaul asked that a

bishop be sent to them, and the Church sent St.

Irenaeus (icon below), who settled at Lyons on the Rhone river.

Among the many works St. Irenaeus accomplished,

the most important were his mastery of the language

of the local Celtic people and his preaching to them

of the Christianity he had received from St.

Polycarp, the disciple of St. John the Theologian.

Saint Irenaeus

By

the 4th century Christianity had reached all the

Celtic peoples, and this "leaven" was preparing

people's hearts to receive the second burst of

Christian missionary outreach to the Celts, through

St. Hilary and St. Martin. (icons

below)

Saint Hilary

Saint Martin

The seeds that St. Irenaeus planted bore abundant

fruit in the person of St. Hilary of Poitiers, who,

having lived in Asia Minor, would be the link

between East and West, transmitting Orthodoxy in its

fullness to the Celtic peoples. He was not only a

great defender of the Faith, but also a great lover

of monasticism. This Orthodox Faith and love for

monasticism was poured into a fitting

vessel—Hilary's disciple, St. Martin of Tours, who

was to become the spiritual forefather of the Irish

people. What Saints Athanasius and Anthony the Great

were to Christianity in the East, Saints Hilary and

Martin were to the West.

By

the 4th century an ascetic/monastic revival was

occurring throughout Christendom, and in the West

this revival was being led by St. Martin. The

Monastery of Marmoutier which St. Martin founded

near Tours (on the Loire in western France) served

as the training ground for generations of monastic

aspirants drawn from the Romano-Celtic nobility. It

was also the spiritual school that bred the first

great missionaries to the British Isles. The way of

life led at Marmoutier harmonized perfectly with the

Celtic soul. Martin and his followers were

contemplatives, yet they alternated their times of

silence and prayer with periods of active labor out

of love for their neighbor.

Some of the monks who were formed in St. Martin's

"school" brought this pattern back to their Celtic

homelands in Britain, Scotland and Wales. Such

missionaries included Publicius, a son of the Roman

emperor Maximus who was converted by St. Martin, and

who went on to found the Llanbeblig Monastery in

Wales—among the first of over 500 Welsh monasteries.

Another famous disciple of St. Martin was

St. Ninian,

who traveled to Gaul to receive monastic training at

St. Martin's feet, and then returned to Scotland,

where he established Candida Casa at Whithorn, with

its church dedicated to St. Martin. The waterways

between Ireland and Britain had been continually

traversed by Celtic merchants, travelers, raiders

and slave-traders for many centuries past, so the

Irish immediately heard the Good News brought to

Wales and Scotland by these disciples of Ninian.

About the same time that the missionaries were

traveling to and from Candida Casa amidst all this

maritime activity, a young man named

Patrick was captured by an Irish raiding party

that sacked the far northwestern coasts of Britain,

and he was carried back to Ireland to be sold as a

slave. While suffering in exile in conditions of

slavery for years, this deacon's son awoke to the

Christian faith he had been reared in. His zeal was

so strong that, after God granted him freedom in a

miraculous way, his heart was fired with a deep love

for the people he had lived among, and he yearned to

bring them to the light of the Gospel Truth. After

spending some time in the land of Gaul in the

Monastery of Lerins, St. Patrick (451), was

consecrated to the episcopacy. He returned to

Ireland and preached with great fervor throughout

the land, converting many local chieftains and

forming many monastic communities, especially

convents.

It

was during the time immediately following St.

Patrick's death, in the latter part of the

5th

century, that God's Providence brought all the

separate streams of Christianity in Ireland into one

mighty rushing river.

While St. Patrick's disciples continued his work of

preaching and founding monastic communities—it was

his disciple, St. Mael of Ardagh (481), for example,

who tonsured the great

St. Brigid of Kildare (523)—several other saints

who were St. Patrick's younger contemporaries began

to labor in the vineyard of Christ. These included

Saints Declan of Ardmore (5th c.), Ailbhe of Emly

(527), and

Kieran of Saighir (5th c.).

Saint Declan Saint Kieran

Saint Brigid

Saint Ailbhe

Then came young Enda from the far western islands of

Aran (off the west coast of Ireland). He studied

with St. Ninian at Whithorn, and thus received the

flame of St. Martin's spiritual lineage with its

ascetical training and mystical aspirations. Having

been fully formed in the Faith, St. Enda (530)

returned to the Aran Islands, where he founded a

monastery in the ancient tradition. It was on the

Aran Islands that the traditional founder of the

Irish monastic movement, St. Finian, drank deep of

the monastic tradition established by St. Martin.

Before Finian's death in a.d. 548, he founded the

monastery of Clonard and was the instructor of a

whole generation of monks who became great founders

of monasteries throughout Ireland, and great

missionaries as well. The most famous of his

disciples were named the "Twelve Apostles of

Ireland," and included Saints

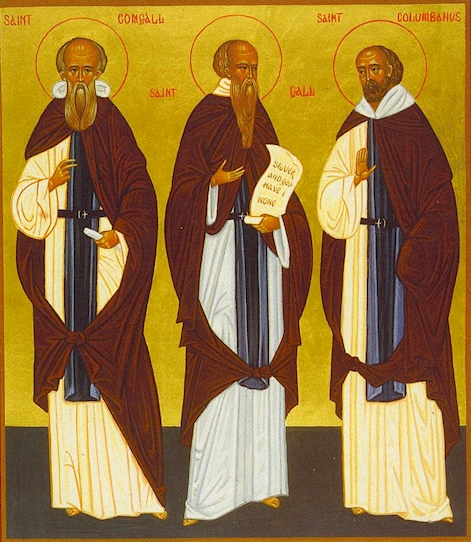

Brendan the Navigator, Brendan of Birr,

Columba of Iona, Columba of Terryglass, Comgall

of Bangor, Finian of Moville, Mobhi of Glasnevin,

Molaise of Devenish, Ninnidh of Inismacsaint,

Sinnell of Cleenish, Ruadhan of Lorrha, and the

great monastic father

Kieran of Clonmacnois. By the middle of the 6th

century these men and their disciples had founded

hundreds of monasteries throughout the land and had

converted all the Irish. And that was only the

beginning...

Saint Brendan

Saints Comgall - Gall - Columbanus

Saint Columba

2. Why was Christianity Received so Quickly in

Ireland?

Why were the Celtic peoples able to receive

Christianity so readily and so eagerly? The Church

Fathers state that God prepared all peoples before

the Incarnation of Christ to receive the fullness of

Truth, Christianity. To the Jews He gave the

Israelite revelation. Among the pagans, faint foreshadowings of the coming revelation were present

in some of their beliefs and best qualities. The

Celtic peoples were no different—in some ways they

were better off than most pagans.

On

a natural level, the Celtic peoples had a great love

of beauty which found overflowing expression as the

Christian Faith, arts and culture developed in

Ireland. Their extreme and fiery nature, which had

previously been expressed through war and bloodshed,

now manifested itself in great ascetic labors and

missionary zeal undertaken for love of God and

neighbor.

Their great reverence for knowledge, especially

manifested in lore, ancient history and law, made it

easy for them to have great respect for the ancient

forms and theology of the Church, which were based

in ancient Israelite tradition. They had a great

love for, and almost religious belief in, the power

of the spoken word—especially in "prophetic

utterances" delivered by their Druid poets and

seers.

These perceived manifestations of "the wisdom of the

Other World" were held in great respect and awe by

the Irish, as transmissions of the will of the gods,

which could only be resisted at great peril. When

many of their Druid teachers wholeheartedly accepted

Christianity, and as Christians spoke the revealed

word of God from the Scriptures or from the Holy

Spirit's direct revelation, the people listened and

obeyed. The Irish possessed an intricate and

detailed religious belief system that was primarily

centered in a worship of the sun, and a tri-theistic

numerology—often manifesting itself in venerating

gods in threes, collecting sayings in threes

(triads), etc.—which led to the easy acceptance of

the true fulfillment of this intuition in the

worship of the Holy Trinity. They also treasured a

very strong belief in the afterlife, conceived as a paradisal heavenworld in the "West" to which the

souls of the dead passed to a life of immortal

youth, beauty and joy.

Even the societal structure of the Celts in Ireland

prepared its peoples for Christianity. In contrast

to the urban-centered and highly organized mindset

which prevailed in the lands under Roman rule,

Ireland (which was never conquered) preserved the

ancient family- and communal-based patterns of rural

societies. They did not build cities or towns, but

settled in small villages or individual family farm

holdings. The only recognized "unit" was the tribe

and its various family clans, centered around their

king's royal hill fort. The economy remained wholly

pastoral, in no way resembling the Roman urban and

civil systems. There were no city centers. The

original apostolic family-based model of an ascetic

community, and its later monastery-based form,

manifested themselves in Ireland as a natural

completion of what was already present. Finally, the

leadership and teaching roles previously held by the

Druids, poets, lawyers and their schools were

naturally assumed by the monks and bishops of the

Church and their monasteries.

Ruins

of Clonmacnoise Monastery (Country

Offaly)

(Image © Research

Machines plc)

Ruins of

Glendalough (County Wicklow)

3. How Christianity Manifested Itself in Ireland

It

was precisely because the monastic communities were

like loving families that they had such a

long-lasting and complete influence on the Irish

people as a whole. These schools were the seedbeds

of saints and scholars: literally thousands of young

men and women received their formation in these

communities. Some of them would stay and enter fully

into monastic life, while others would return to

their homes, marry, and raise their children in

accordance with the profound Christian way of life

that they had assimilated in the monastery. Some of

the monks, either inspired by a desire for greater

solitude, or by zeal to give what they had received

to others, would leave the shores of their beloved

homeland and set out "on pilgrimage for Christ" to

other countries. Once again they would travel along

paths previously trodden by their ancestors—both the

pagans of long ago, and Christian pilgrims of more

recent times.

Because these monastic communities were centers of

spiritual transformation and intense ascetic

practice, they generated a dynamic environment which

catalyzed the intellectual and artistic gifts of the

Irish people, and laid them before the feet of

Christ. In these monasteries, learning as well as

sanctity was encouraged.

The Irish avidly learned to write in Latin script,

memorized long portions of the Scriptures

(especially the Psalms), and even developed a

written form for their exceedingly ancient oral

traditions. When the Germanic peoples invaded the

Continent (A.D. 400-550), the Gallic and Spanish

scholars fled to Ireland with their books and

traditions of the Greco-Roman Classical Age. In

Ireland these books were zealously absorbed,

treasured and passed on for centuries to come. Many

Irish monks dedicated their whole lives to copying

the Scriptures—the Old and New Testaments, as well

as related writings—and often illuminated the

manuscript pages with an intricate and beautiful art

that is one of the wonders of the world.

4. The Significance of the Orthodox Church in

Ireland for Today

Much has been written about Ireland's wandering

missionary scholars (see Thomas Cahill's bestselling

book, How the Irish Saved Civilization).

The vibrant, community-centered way of life and the

deep, broad, ascetic-based scholarship of the Irish

monks revitalized the faith of Western European

peoples, who were both devastated by wave after wave

of barbarian invasions and threatened by

Arianism.

More than this, the Irish monks evangelized both the

pagan conquerors and those Northern and Eastern

European lands where the Gospel had never taken

root.

For Orthodox Christians, however, there are further

lessons to be gained from the examples of the Irish

saints. These saints were formed in a monastic

Christian culture almost solely based on the "one

thing needful" and the otherworldly essence of

Christian life. They represented Christ's Empire,

and no other. They were Christ's warriors, motivated

solely by love of God and neighbor, acting in

accordance with a clear and firmly envisioned set of

values and the goal of Heaven. Such selfless

embodiments of Christian virtues are all the more

important to us today, who live in an age

characterized by the absence of such qualities. The

unwavering dedication of the Irish monks drew the

Holy Spirit to them. And when He came, He not only

deepened and established their already-present

resolution, but also filled them with the energy and

grace to carry it out. This is what is needed and

yearned for today.

The task of the Orthodox Christian convert in the

West today is to bridge the gap between our time and

the neglected and forgotten saints of Western

Europe, who were our spiritual forebears. As St.

Arsenios said: "Britain will

only become Orthodox when she once again begins to

venerate her saints."

In this task we are very

fortunate to have had a living example of one who

did this: St. John Maximovitch. During his years as

a hierarch he was appointed to many different lands,

including France and Holland. One of the first

things he set out to do upon reaching a new country

was

to tirelessly seek out, venerate and promote the

Orthodox saints of that land, that he might

enter into spiritual relationship with those who did

the work before him, and enlist their help in his

attempts to continue their task. He considered the

glorification and promotion of local Orthodox saints

as one of the most important works that a hierarch

could do for his flock.

We

too must actively labor to venerate our ancestral

saints, and must enter into spiritual relationship

with them as St. John did. While we should not

merely "appreciate" their lives and their example as

an intellectual or aesthetic exercise, neither

should we selectively reinterpret their examples and

way of life in the light of modern fashions and

"spiritualities." We should, through our efforts,

strive to bring these saints into as clear a focus

as possible before our mind's eye, reminding

ourselves of the fact that they are alive and are

our friends and spiritual mentors. The saints are,

according to St. Justin Popovich of Serbia (1979),

the continuation of the life of Christ on earth, as

He comes and dwells within the "lively stones" (cf.

I Peter 2:5) that constitute His Body, the Church

(cf. Eph. 1:22-23). Therefore, honor given to the

saints is honor given to Christ; and it is by giving

honor to Christ that we prepare ourselves to receive

the Holy Spirit.

May the saints of Ireland come close to us and bring

us to the Heavenly Kingdom together with them. Amen.

◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊◊

Short Lives of

Irish Saints Found in the 2003 St. Herman Calendar

ST. KIERAN OF CLONMACNOIS

ST. KIERAN OF CLONMACNOIS

September 9 (545)

The great St. Columba of Iona (June 9, 597)

described St. Kieran as a lamp, blazing with the

light of knowledge, whose monastery brought wisdom

to all the churches of Ireland. This earthly angel

and otherworldly man was born in 512, the son of a

carpenter who built war chariots. He was spiritually

raised by St. Finian in Clonard (December 12, 549)

and was counted among his "twelve apostles to

Ireland." After spending some time in Clonard, the

childlike, pure, innocent, humble and loving Kieran

set off to dwell in the wilderness with his God.

After three years, when more and more disciples

began to come to him, he finally established a

monastery in obedience to a divine decree shortly

before he reposed. He was taken by his Lord to dwell

with Him eternally at the age of 33. "Having lived a

short time, he fulfilled a long time, for his soul

pleased the Lord" (Wisdom 4:13).

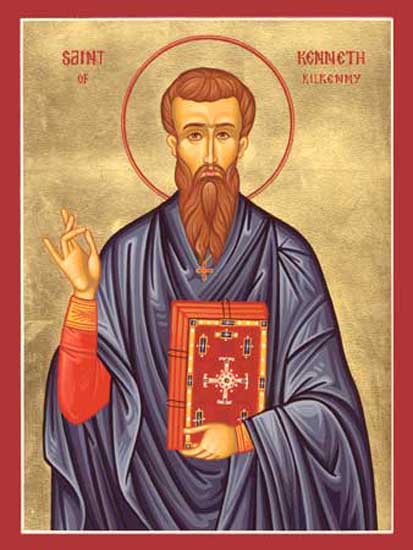

ST. KENNETH OF KILKENNY

ST. KENNETH OF KILKENNY

October 11 (600)

St. Kenneth was the son of a scholar-poet from

Ulster. By race he was an Irish Pict and spoke the

Pictish language. He was a disciple of the great

monastic Saints Finian of Clonard (December 12,

549), Comgall of Bangor (May 11, 603), Kieran of

Clonmacnois (September 9, 545) and Mobhi of

Glasnevin (October 12, 544). After the death of St.

Mobhi he took counsel from St. Finian. As a result

(says the Martyrology of Oengus),

St. Kenneth sailed off to Scotland. There he lived

for a while on the isle of Texa, according to The

Life of St. Columba by St. Adamnan of Iona

(September 23, 704). While there he often visited

his old friend St. Columba (who had lived with him

in Glasnevin before departing for Iona) and helped

him in his missionary labors to the Picts. Later, he

traveled back to Ireland, where he founded the

Monasteries of Aghaboe and Kilkenny before his death

in the year 600.

ST. FINIAN OF CLONARD

ST. FINIAN OF CLONARD

December 12 (549)

St. Finian, known as the "Tutor of the Saints of

Ireland," stands with St. Enda of Aran at the head

of the patriarchs of Irish monasticism. He showed

great zeal and piety for God from his youth. He had

already founded three churches before he set off for

Wales to study at the feet of St. Cadoc at

Llancarfan (September 25, 577). In Llancarfan he

became close friends with St. Gildas (January 29,

ca. 570), another of St. Cadoc's disciples. Upon his

return to Ireland, he founded the great Monastery of

Clonard during the very same year the great St. Enda

(March 21, 530 ) reposed in Aran. A multitude of

illustrious and holy men studied under St. Finian,

including the famous "Twelve Apostles of Ireland."

St. Finian founded many other monasteries during his

lifetime, including the famous island monastery of

Skellig Michael off the southwest coast of Ireland.

ST. ITA OF KILEEDY

ST. ITA OF KILEEDY

January 15 (570)

The gentle and motherly St. Ita was descended from

the high kings of Tara. From her youth she loved God

ardently and shone with the radiance of a soul that

loves virtue. Because of her purity of heart she was

able to hear the voice of God and communicate it to

others. Despite her father's opposition she embraced

the monastic life in her youth. In obedience to the

revelation of an angel she went to the people of Ui

Conaill in the southwestern part of Ireland. While

there, the foundation of a convent was laid. It soon

grew into a monastic school for the education of

boys, quickly becoming known for its high level of

learning and moral purity. The most famous of her

many students was St. Brendan of Clonfert (May 16,

577). She went to the other world in great holiness

to dwell forever with the risen Lord in the year

570.

ST. BRIGID OF KILDARE

ST. BRIGID OF KILDARE

February 1 (523)

The well-known founder and abbess of the Monastery

of Kildare has been revered and loved throughout

Europe for almost fifteen hundred years. While she

was still a young woman, her unbounded compassion

for the poor, the sick and the suffering grew to

such proportions as to shelter all of Ireland. St.

Brigid's tonsure at the hands of St. Mael of Ardagh

(February 6, 488) inaugurated the beginning of

women's coenobitic monasticism in Ireland. St.

Brigid soon expanded it by founding many other

convents throughout Ireland. The gifts of the Holy

Spirit shine brightly upon all through her—both men

and beasts—to this day. After receiving Holy

Communion at Kildare from St. Ninnidh of

Inismacsaint (January 18, 6th c.) she gave her soul

into the hands of her Lord in 523.

ST. GOBNAIT OF BALLYVOURNEY

February 11 (7th c.)

The future abbess and founder of the Ballyvourney

Convent was born in the 6th century in the southern

lands of Ireland. To escape a feud within their

family, her household fled west to the Aran Islands

and dwelt there for some time. It is possible that

her family accepted Christianity while living in the

islands. Gobnait began to zealously manifest her

faith through her deeds, founding a church on the

Inisheer Island. When she returned east with her

family, she encountered St. Abban of Kilabban (March

16, 650), who became her spiritual mentor. Her

family, greatly moved by their daughter's faith,

gave her the land on which she and St. Abban founded

the Monastery of Ballyvourney. In Ballyvourney her

sanctity quickly revealed itself, especially through

the abundant healings God worked through her

prayers. Even the many bees that she kept paid her

obedience, driving off brigands and other unwelcome

visitors.

ST. OENGUS THE CULDEE

ST. OENGUS THE CULDEE

March 11 (824)

While still a youth St. Oengus entered the Monastery

of Cluain-Edneach, which was renowned for its strict

ascetic life and was directed by St. Malathgeny

(October 21, 767). He had an especially great love

for the Lives of the Saints. After his ordination to

the priesthood, he withdrew to a life of solitude.

For his holy way of life many called him the "Cile

D" (Culdee) or "the friend of God." After many

people disturbed his solitude, he slipped away

secretly and entered the Monastery of Tallaght,

which was then directed by St. Maelruin (July 7,

792). He entered the monastery as a lay worker,

laboring at the most menial tasks for seven years

until God revealed his identity to St. Maelruin.

There he mortified his flesh with such ascetic feats

as standing in icy water. St. Oengus wrote the

Martyrology of Tallaght with St. Maelruin. After

Maelruin's death in 792, St. Oengus returned to

Cluain-Edneach and wrote many more works in praise

of the saints, including his well-known Martyrology

and the Book of Litanies. He reposed in 824 and

became the first hagiographer of Ireland.

ST. PATRICK OF IRELAND

ST. PATRICK OF IRELAND

March 17 (451)

The most famous of all the saints of the Emerald

Isle is undoubtedly her illustrious patron St.

Patrick. Reared in Britain and the son of a deacon,

St. Patrick was captured and enslaved by Irish

raiders while still a youth. Thus, he was carried

off to the land he would later enlighten with the

Gospel: Ireland. During his captivity, the faith of

his youth was aroused in him, and shortly thereafter

he miraculously escaped his servitude. Some years

later, he received a divine call to bring his

new-found faith back to the Irish. For this task, he

prepared as best he could in Gaul, learning from St.

Germanus of Auxerre (July 31, 448) and the fathers

of the Monastery of Lerins. While in Ireland he

ceaselessly traveled and preached the Christian

Faith to his beloved Irish people for almost twenty

years until his blessed repose in 451.

ST. ENDA OF ARAN

March 21 (530)

St. Enda is described as the "patriarch of Irish

monasticism." After many years living as a

warrior-king of Conall Derg in Oriel, St. Enda

embraced the monastic life. His interest in

monasticism originally grew as a result of the death

of a young prospective bride staying in the

community of his elder sister, St. Fanchea (January

1, ca. 520). St. Fanchea suggested that he enter the

Whithorn Monastery in southwestern Scotland. After

some years in Whithorn he returned to Ireland and

settled on the fallow, lonely Aran Islands off her

western shores. During the forty years of his severe

ascetic life there, he fathered many spiritual

disciples—including Sts. Jarlath of Cluain Fois

(June 6, 560) and Finian of Clonard (December 12,

545)—and laid the foundation for monasticism in

Ireland. St Enda reposed in the year 530 in his

beloved hermitage on Aran.

ST. DYMPHNA, WONDER-WORKER AND MARTYR OF GHEEL

ST. DYMPHNA, WONDER-WORKER AND MARTYR OF GHEEL

May 15 ( early 7th c.)

St. Dymphna was the daughter of a pagan king and a

Christian mother in Ireland. When her mother died,

her father desired to take his own daughter to wife.

Dymphna fled with her mother's instructor, the

priest Gerberen, to the continent. Her father

followed and eventually found them. When Dymphna

refused to submit to his unholy desire, he had them

both beheaded at Gheel in what is today Belgium.

Throughout the centuries she has shown special care

and concern from the other world for those suffering

from mental illnesses and is greatly venerated

throughout Europe and America.

ST. KEVIN OF GLENDALOUGH

ST. KEVIN OF GLENDALOUGH

June 3 (618)

The path of St. Kevin's early life was well laid.

When St. Kevin was between the ages of seven and

twelve, he was tutored by the desert-loving St.

Petroc of Cornwall (June 4, 594), who was then

studying in Ireland. After St. Petroc left for

Wales, the twelve-year-old St. Kevin entered the

Monastery of Kilnamanagh. There his humility and the

holiness of his life amazed all. After his

ordination to the priesthood he followed his tutor's

desert-loving example and set out to establish his

own hermitage. He settled in an ancient pagan

cave-tomb on a crag above the upper lake of

Glendalough. For many years he lived in this

beautiful desert wilderness like another St. John

the Baptist. All the animals behaved toward him as

with Adam before the Fall. Disciples soon gathered

around him and St. Kevin was constrained to become

the founder and Abbot of the famous Glendalough

Monastery. He died at the great old age of 120 in

618 and went to his Lord.

ST. COLUMBA OF IONA

ST. COLUMBA OF IONA

June 9 (597)

St. Columba (or Columcille) is one of the greatest

of all the saints of Ireland. Born into an

exceedingly prominent noble family, the Ui-Niall

clan, he forsook his wealth and all earthly

privileges and laid his ample natural gifts at the

feet of the Lord, becoming a monk at a young age. He

studied under some of the holiest men of his day,

including Saints Finian of Clonard (December 12,

549) and Mobhi of Glasnevin (October 12, 545). After

St. Mobhi's death, St.Columba went on to found the

monasteries of Derry and Durrow. He traveled as a

missionary throughout his beloved Ireland for almost

20 years. In 565 he settled on the island of Iona,

off the west coast of Scotland, where he remained

for 32 years and brought about the conversion of

many. He reposed on Iona in great holiness on June

9, 597.

ST. COWEY OF PORTAFERRY, ABBOT OF MOVILLE

ST. COWEY OF PORTAFERRY, ABBOT OF MOVILLE

November __ (8th c.)

St.

Cowey is a little-known monastic saint who lived

near the tip of the Ards Peninsula in the late 7th

and early 8th centuries. For many years he labored

there as a hermit, sending up his prayers to God

during his long nightly vigils in the depths of the

forest. Three holy wells are still to be found where

he labored, as well as an ancient church built

amidst them, which looks eastward over the Irish Sea.

Beside the church, an ancient cemetery completes the

view that greets the pilgrim's eye. St. Cowey's

holiness attracted many to his quiet, little

hermitage. Tradition holds that he was made abbot of

the great Moville Monastery further north on the

peninsula in 731, possibly shortly before he reposed

around the middle of the 8th century. His memory has

been kept and treasured by the local inhabitants of

the nearby town of Portaferry for over twelve

hundred years.

ST. SUIBHNE OF DAL-ARAIDHE

(

late 7th century)

Both the early Church of Syria and the early Church

of Ireland were famous for their extraordinary

ascetics—men and women who were so affected by the

touch of Divinity that they fled from all that might

interfere with their struggle, even renouncing their

reason. Syria gave the Church the stylites, and also

the "grazers": severe ascetics who lived almost like

animals, having no dwellings and eating whatever

vegetation grew in their vicinity. The Irish

manifested a similar form of sanctity in the geilt,

who were a cross between fools-for-Christ and the

Syrian grazers. The most famous of all the geilt was

St. Suibhne of Dal-Araidhe, formerly a violent Irish

chieftain whose murdeous ways brought the curse of

God upon him. In his profound repentance, he took

upon himself the extreme ascetic way of life of the

geilt, living in the open-air wilderness. Before St.

Suibhne died he gave a life confession to his

spiritual father, St. Moling (722). St. Moling

preserved this account in the form of a long poem.

This poem has come down to us today, having been

only slightly altered over the years (in very

obvious places). It is not only very beautiful

poetry but also a spiritually instructive

autobiographical document. The Saint foresaw that

since he had previously lived by the sword, he would

die by violent means. He was murdered at the end of

the 7th century in St. Moling's monastery and buried

nearby.