While the hierarchy of the Church in Greece was actually asking the faithful to

participate as volunteers in the 2004 Athens Olympics, the neo-pagans were

accusing Christians of having supposedly put an end to a…..sublime Olympic

ideal, centuries ago...... Just

how “sublime” was this institution?

*********************

A few months ago I was attending

a Divine Liturgy when the priest surprised us with an announcement that

he read, issued by the hierarchy of the Church of Greece. The

announcement was prompting the faithful to offer their voluntary

services – no less – for the….. 2004 Athens Olympics (!!!)

At that very moment, I stopped to

ask myself: What do Christians have to do with exhibitions that involve

the igniting of a “sacred flame” and rituals of priestesses belonging to

the ancient Hellenes’ idolatrous religion?

Of course The hierarchy was

striving to show that the Church always supports the athletic ideal, and

even more so, because the Church has recently been accused of having put

an end to the Olympics centuries ago. The hierarchy chose to make a

political move for the sake of giving a good impression and also to not

displease those who still harbored nostalgia for such events….

Naturally the modern Olympics

bear no resemblance to the ancient ones that the Church had ended for

their pagan barbarity; We would therefore like to take the opportunity

to remind our readers in this article what the Olympics meant to the

civilization of ancient times. What, indeed, was that famous “Olympic

ideal” that we are constantly reminded of by the various “factors” who

are embroiled in these events? And what –finally– were

the actual reasons that made the ancient Christians discontinue this

barbarity?

Opinions

on the Olympics by ancient citizens

There are those who speak of the

Olympic ideal that was discontinued by the “evil Christians”. However,

the truth of the matter is far different. In order to secure a

self-indulgent lifestyle, the professional athletes did not hesitate to

resort to all sorts of illegal and dishonorable acts. They “sold and

purchased the victories” (πωλείν

τε και

ωνείσθαι τα

νίκας) at Olympia; some, for the sake of

making money and others, in order to avoid perilous confrontations. This

profiteering was even promoted by the athletes’ trainers, who “made

provisions for their personal profit” (προνοούντες

του εαυτών

κέρδους) [see Philostratos: Gymnastikos (Φιλόστρατος:

Γυμναστικός), p.43].

According to Galen, in his work

“Exhortative, on the arts” [ Γαληνός:

Προτρεπτικός επί

τας τέχνας ] pages

9-14, the athletic art cultivated deception. Tough physical training did

not render anyone more powerful than the creatures of the animal world;

people should be honored for their achievements in the civilized arts.

“Only the best among people should be deserving of divine honor, not for

doing well in contests, but for the benefit acquired from the arts” (

τών ανθρώπων

γαρ αρίστους

θεία αξιωθήναι

τιμή, ουχ

ότι καλώς

έδρασαν εν

τοις αγώσιν,

αλλά δια

την από

τών τεχνών

ευεργεσίαν ). All natural riches are either

spiritual or physical. No other category of riches exists. Athletes

never dream of such riches; they have no logic. They continuously

accumulate flesh and blood and they preserve their spirit lifeless, like

the animals. “Because, by constantly incrementing masses of flesh and

blood, it is as though they have extinguished their soul in a large

mire, (rendering it)

unable to understand anything with precision, only mindless, and similar

to the reasonless animals” ( Σαρκών

γαρ αεί

και αίματος

αθροίζοντες πλήθος,

ως εν

βορβόρω πολλώ

την ψυχήν

εαυτών έχουσιν

κατασβεσμένην, ουδέν

ακριβώς νοήσαι

δυναμένην, αλλ'

άνουν, ομοίως

τοις αλόγοις

ζώοις ). Galen reminds us of Hippocrates’

words, that: “health implies a control over food and labor. Measure is

required everywhere.” And he says that on the contrary, there is no

state more unstable than that of athletes’ health: “…for they say that

everything in excess is hostile to nature” ( παν

γαρ, φησί,

το πολύ

τη φύσει

πολέμιον ). Galen compares the life of

athletes to that of pigs; the difference being that pigs are not forced

to toil or eat: “…so that their way of life is regarded as the behaviour

of swine…” ( ώστε εοικέναι τον βίον αυτών υών διαγωγή

).

A

huge pecuniary

bazaar

Pindar’s hymns honoring Olympic

victors were regarded by everyone as a commodity for sale. Those who

were unsuccessful in the Olympics and other games usually returned to

their homeland completely humiliated and despised. They would hide in

narrow sidestreets in order to avoid their enemies, on account of their

failure. “…making themselves invisible to enemies, in secluded places,

having being struck by misfortune…” ( κατά λαύρας δ'

εχθρών απάοροι πτώσσοντι, συμφορά δεδαγμένοι ), in

Pythionikes (Πυθιονίκες 8). In exchange

for a generous sum of money, Pindar would even laud tyrants such as

Hieron of

Syracuse

and

Theron of Akragas,

who had “won” the contests by paying off their opponents as well as the

judges. In 488 b.C., Hieron was the “winner” of the equestrian events at

Delphi, also in 476 b.C. at Olympia, without any personal involvement in

the contests, and yet Pindar exalted him as one who “reaps virtues”

[Olympic Victors (Ολυμπιονίκες) 1, vs.17-20 ].

In fact, Pindar even lauds victors of the brutal, no-holds-barred

“Pancration” wrestling contest, as in the case of

Pytheas at Nemea

[Olympic Victors (Ολυμπιονίκες), 1].

In 372 b.C. (at the 102nd

Olympiad), one of the judges, Troilus, actually participated in a

chariot race when it was forbidden for judges to participate in the

events themselves (Pausanias: Travelling around Hellas (Ελλάδος

περιήγησις), VΙ, 1,

51). He was naturally declared an Olympic champion and his statue was

erected at the sacred Altis of Olympia. Two other judges had proclaimed

Eumolpos an Olympic victor, following a secret agreement. However this

was discovered and they were obliged by the Representative Body of the

games to pay a fine (Pausanias, Travelling around Hellas (Ελλάδος

περιήγησις), VΙ, 3,

7). According to Plutarch, (On relenting - Περί

δυσωπίας 17, 535c), the judges would grant

victory wreaths after submitting to bribery and other immoral

transactions, to persons who were irrelevant to the contests.

Many athletes would bribe their

opponents in order to become Olympic champions themselves. In 388 b.C.

(at the 98th

Olympiad), Eupolos the pugilist from Thessaly bribed his three opponents

(Pausanias: Travelling around Hellas (Ελλάδος

περιήγησις), V, 21, 5). One of them who had

taken the bribe was also a victor of previous Olympics.

As Philostratos writes, one could

freely sell the victory wreath and just as freely buy it. “As for the

wreath of Apollo or of Poseidon, they were bestowed by permission and

were purchased by permission.” ( στέφος δε Απόλλωνος

ή Ποσειδώνος άδεια μεν αποδίδοσθαι, άδεια δε ωνείσθαι ) [see

Philostratos: Gymnastikos

(Φιλόστρατος: Γυμναστικός), p.45].

There are many more examples of

bribery between athletes that we could mention, WHICH WERE EITHER

PERCEIVED AT THE TIME OR HAPPENED TO BE PRESERVED TO THIS DAY.

Let us now examine a few other

details.

Let us

examine the sale and purchase of athletes

Four years after Astylos’ (an

athlete from Croton) victory at Olympia in 488 b.C., Hieron, the tyrant

of Syracuse purchased him so that he would participate in the next

Olympics as a Syracusian. Thus, in 484 b.C., his victory was for

Syracuse. (Pausanias VI 13,1). The Cretan Sotades was the winner of the

“dolichos” race during the 99th

Olympiad. In the next Olympiad, he was purchased by the City of Ephesus

and appeared in Olympia as an Ephesian athlete (Pausanias VI 18,6).

Olympic champions were “used” by

cities as diplomats, as colonialists and as generals. Statues of them

were erected, not only in their home towns, but also in Olympia, in lieu

of an advertisement. (Pausanias VI 1 - 18).

According to Philostratos, the

athletes of his time (3rd

century A.D.) wallowed in luxury and prestige. They accepted bribes

because they needed money to support their squandering lifestyle; others

bribed their co-athletes simply because they were not in a position to

achieve victory. “For some of them also applied themselves to a personal

glory by taking from many, while others are purchased, who do not desire

victory with pains, on account of a carefree lifestyle..”

( Οι μεν γαρ και αποδίδονται την εαυτών εύκλειαν, δι'

οίμαι, το πολλών δείσθαι, οι δε ωνούνται το μη ξυν πόνω νικάν δια το

αβρώς δαιτάσθαι [see Philostratos:

Gymnastikos (Φιλόστρατος: Γυμναστικός),

p.45].

The guise

of the contests

On a coin of Verria there is a

man holding a whip, representing the assistant of a contest organizer.

Coins from Pergamus and Lydia likewise bore scenes of flagellators

whipping ill-natured athletes.

In the 5th

century b.C. (456 και 452) wrestling contests,

Leoniscos from Messina had found it impossible to throw down his

opponent and so resorted to grabbing his fingers and crushing them, as a

result of which, his opponent suffered so many fractures that he was

forced to abandon the contest. In this manner, he had managed to be

twice proclaimed Olympic champion. His statue was however erected in the

city of Regium, given that a sign was discovered in Olympia which

forbade the crushing of opponents’ fingers (Pausanias, Travelling around

Hellas (Ελλάδος περιήγησις

VI, 4,30).

Loukianos mentions in his

revealing work titled “Anacharsis, or, on gymnastics” (Ανάχαρσις,

ή περί

γυμνασίων

):

“Tell me Solon, why are Athenian

youths making a habit of these obscenities? They tussle with each other,

they trip each other over, they try to strangle one another by squeezing

their neck, they twirl the other’s body around, they sink in the mud and

they roll around in it like pigs. They push each other and they lower

their heads and attack each other like rams. Look! That one there has

grabbed the other by the legs and has tossed him to the ground and has

fallen on top of him and is pushing him into the mud. Now he has wrapped

his legs around the other’s waist, he is passing his arm under his neck

and is squeezing the poor fellow who is beating him on the shoulder,

begging him, I’m sure, to avoid being strangled completely.” [Anacharsis,

or, on gymnastics (Ανάχαρσις,

ή περί

γυμνασίων ), 1].

Let us

take a look at Pugilism (boxing)

Apollodorus the story-writer

refers to Hercules who used to crush his opponents’ ribs: a “heroic”

model for Olympic athletes…

Apollodorus the story-writer

refers to Hercules who used to crush his opponents’ ribs: a “heroic”

model for Olympic athletes…

An inscription that was

discovered on the island of Thera (Santorini)

says that pugilism “is won with blood”.

Artemidorus writes of pugilism

that “…contests with punches are dangerous for everyone. They not only

are a disgrace, they also cause calamities. The face is disfigured and

blood flows abundantly.”

During the Minoan era, the

“gloves” worn by pugilists were reinforced with hard coatings, while in

a mural of Thera one can see that a protective helmet was worn by the

fighters, around 1500 b.C..

In Homeric times, pugilism was

seen as a catastrophic contest – an indication of what was going on in

ancient Greece. Odysseus confronts the beggar Iros in Ithaca; he punches

him below the ear, splinters the bones, thus flooding Iros’ mouth with

blood. (Homer: Odyssey

vs.95-98)

From the 4th

century onward, instead of the bare fists that were customary until then

for pugilism, the fingers began to be bound – supposedly to safeguard

the fingers. Philostratos mentions that the four fingers were bound with

a small leather strap. Later on however, they would wrap the entire fist

with straps made from ox hide, designed to inflict more severe blows to

their opponents. [see Philostratos: Gymnastikos (Φιλόστρατος:

Γυμναστικός), p.10].

In Roman times, pugilists wore

leather “gloves” reinforced with pellets of iron and lead. This item was

known as “caestus”. (Pausanias, Travelling around Hellas (Ελλάδος

περιήγησις Η, 48).

Plato also refers to the pellets

in pugilists’ “gloves”, which had replaced the leather straps. [Plato:

Laws (Πλάτων: Νόμοι

830Β, and Pausanias: Travelling around Hellas

(Ελλάδος περιήγησις,

2, VI, 23). Also used from the 3rd

century onwards were the “spiked straps” (ιμάντες

οξείς), which had metallic spikes attached to

the leather straps. They were named “myrmiges” (μύρμηγκες

=ants), because they were

used to inflict ant-shaped punctures, just like the Roman kind and were

followed by slaughter. “…a spiked strap was upon the wrist of each hand”

(Ιμάς οξύς

επί τω

καρπώ τής

χειρός εκατέρας)….

“…This form of murder provoked pain that was attributed to the

unquenchable menace of pugilism, irritating the fighter who would

furiously swing his arms about wrapped with myrmiges, thus aggravating

his thirst to kill…” ( Πυγμαχίης δ' ώδινε φόνου

διψώσαν απειλήν ιγνιστόρους μύρμηκας εμαίνετο χερσίν ελίσσων. Πυγμάχου

δ' ώδινε

φόνου διψώσαν

απειλήν ). Thick straps with metallic spikes

were also wrapped around the arms up to the elbow, turning it into a

deadly bludgeon. In the 6th

century b.C. Pausanias mentions that they no longer used the “spiked

straps”, but the “gentle” ones (μειλίχες)

which only inflicted wounds and caused fractures (Pausanias, Travelling

around Hellas (Ελλάδος περιήγησις VIII, 40,3).

Eurydamas from Cyrene won a

pugilist contest, but all his teeth had meantime been broken by his

opponent. In order to hide this, he had swallowed all of them. [Aelianus,

Miscellaneous History (Αιλιανός,

Ποικίλη Ιστορία,

10,19)].

Eurydamas from Cyrene won a

pugilist contest, but all his teeth had meantime been broken by his

opponent. In order to hide this, he had swallowed all of them. [Aelianus,

Miscellaneous History (Αιλιανός,

Ποικίλη Ιστορία,

10,19)].

In 496 b.C., the pugilist

Cleomedes from Astypalaia island had killed Iccus from Epidaurus. He had

struck a blow to his opponent’s ribs which caused an opening in the

flesh; he then plunged his hand into the opening and ripped out his

lung. Given that this victory was not recognized, he returned to his

island, went into a school where 60 children were attending class,

smashed the pillar that was supporting the roof, bringing down the

entire building and causing the death of all the students. The

Astypalaians went to consult the Oracle at Delphi and received the

following reply: “Cleomedes is the last of the heroes. Honor him with

sacrifices, for he is not a mortal.” (Pausanias, Travelling around

Hellas (Ελλάδος περιήγησις

V, 2, 6-8 and Eusebius: Evangelical Preparation, V, 32).

The patron “god” of Pugilism was

Apollo and it was for this reason that he also given the title of

“Pugilist” (Πύκτης) (Homer: Iliad 23, v.660).

Let us

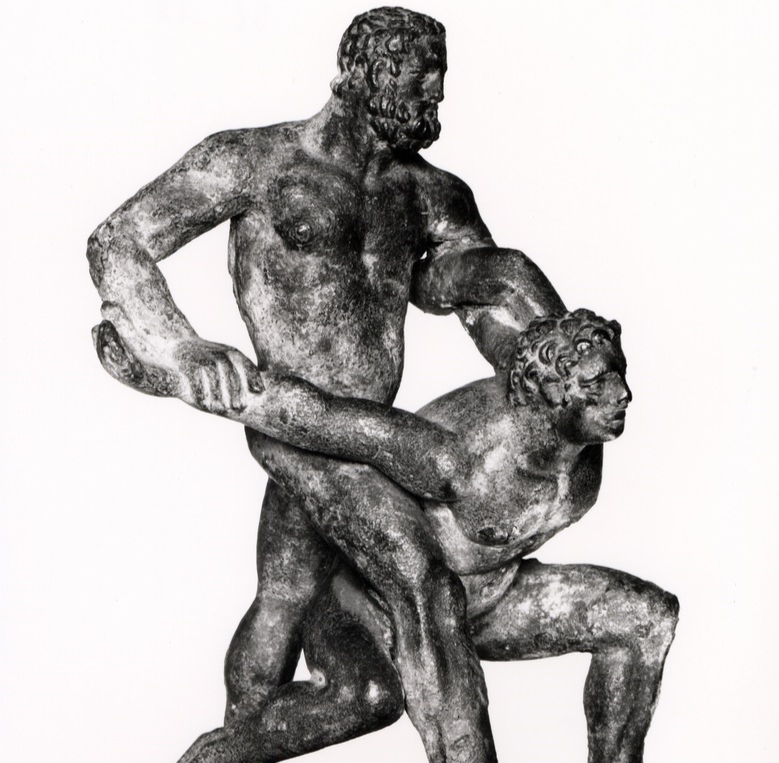

take a look at the “Pancration”

The “Pancration” (=no

holds barred) was not

a marginal sport of the Olympics. In Olympia, the Pancration was

regarded as “the most beautiful of contests” and statues of those

barbaric athletes were made, honoring their bestiality. [Philostratos,

Images (Φιλόστρατος, Εικόνες, 2)].

The “Pancration” (=no

holds barred) was not

a marginal sport of the Olympics. In Olympia, the Pancration was

regarded as “the most beautiful of contests” and statues of those

barbaric athletes were made, honoring their bestiality. [Philostratos,

Images (Φιλόστρατος, Εικόνες, 2)].

During a Pancration bout between

two Lacedemonians, the one had grabbed his opponent by the neck, swung

him around and tossed him to the ground; however, he managed to bite the

attacker’s arm. His attacker then shouted “You Laconian! You bite like

women do!” “No” replied the other, “I bite like lions do!” [Plutarch,

Laconic Maxims (Πλούταρχος αποφθέγματα

Λακωνικά, 234,44)].

The Athenian cynic philosopher

Dymonax was overwhelmed when he saw a Pancration fighter bite like a

lion. [Loukianos: Dymonax (Λουκιανός

Δημώναξ 49)].

On two ancient vases there are

representations of Pancration fighters, poking out the eyes of their

opponents with their finger. (K.Simopoulos: “Olympiads - Myth, fraud and

barbarity”, page 97).

In wrestling matches, as in the

Pancration, even strangulation of the opponent was allowed. Any kind of

savagery was legitimate: fractures, crushing of hands, feet, ribs, even

spines. And this was supposedly “athletic education” and an “athletic

ideal”……..

Pancration fights first appeared

in 648 b.C. (33rd

Olympiad) and 200 b.C. (145th

Olympiad) and were later taught to children. Just imagine parents

actually sending their children to be mutilated by such a barbaric

sport! [see Philostratos: Gymnastikos (Φιλόστρατος:

Γυμναστικός), p.45]. Everything was permitted:

dislocating joints, breaking bones, strangling, causing death by all

possible means. Kicking knees and groins was customary, as discerned in

pottery of that era. As early as the 6th

century b.C., one could press the opponent’s face into the sand, forcing

him to either swallow it or inhale it… (Loukianos: “Anacharsis, or, on

gymnastics” (Ανάχαρσις, ή

περί γυμνασίων, 3)

The first consequence of a

Pancration encounter was –according to Philostratos– the distortion of

arms and legs. [Philostratos, Images (Φιλόστρατος,

Εικόνες, Ι 6,

ΙΙ 6)]. The final results were the

strangulation of the opponent – a sight that greatly enthused the

spectators. The inhabitants of Ilis, Philostratos tells us, actually

lauded strangulation during the Pancration. [Philostratos, Images (Φιλόστρατος,

Εικόνες, ΙΙ 6)].

Loukianos writes the following:

“They stand up, throw themselves against each other and beat each other

with arms and legs. One poor fellow spat out his broken teeth, as his

mouth was filled with blood and sand after having received a blow to his

chin. The overlord sees these calamities, but does not give the command

to stop the event or abolish it. On the contrary, he exhorts the

Pancration contestants and praises the one who has struck the final

deadly blow.” (Loukianos: “Anacharsis, or, on gymnastics” (Ανάχαρσις,

ή περί γυμνασίων, 3).

The Pancration fighters of

Lacedaemon would mangle their opponents with tooth and nail; they would

blind them by wrenching out their eyeballs [Philostratos, Images (Φιλόστρατος,

Εικόνες, ΙΙ 6)].

The sophist Julius Polydeukis (2nd

century A.D.) writes that the terms “pancration” and “pancratist”

signified strangulation, choking, kicks and punches.” (Polydeukis,

Onomastikon, 3, 150).

Arrachion, whose statue was

erected in the marketplace of the city of Figaleia, had been immobilized

in a match by an opponent pancratist and was trapped between the other’s

legs while attempting to choke him by squeezing his hands around his

neck. Arrachion succeeded in crushing one of the toes of his opponent,

but died immediately after. (Pausanias, Travelling around Hellas (Ελλάδος

περιήγησις VIII, 40,2).

In another instance, the two

opponent pancratists – Kreugas of Epidamnos and Damoxenus of Syracuse –

had agreed after a prolonged, victor-less match, to strike down the one

who would remain standing and motionless. Kreugas struck a blow to

Damoxenus’ head, without any dangerous consequences. Damoxenus struck

Kreugas’ side with fingers outstretched; he pierced his flesh and then

ripped out the bowels with his hands. Kreugas died immediately. (Pausanias,

Travelling around Hellas (Ελλάδος

περιήγησις VIII, 40).

I don’t think much more needs to

be said….

(The information in this article was taken from the exceptional book

by Kyriakos Simopoulos, “The Olympiads: Myth, Fraud and Barbarity”,

Stahe Publications. Athens 1998).

Apollodorus the story-writer

refers to Hercules who used to crush his opponents’ ribs: a “heroic”

model for Olympic athletes…

Apollodorus the story-writer

refers to Hercules who used to crush his opponents’ ribs: a “heroic”

model for Olympic athletes… Eurydamas from Cyrene won a

pugilist contest, but all his teeth had meantime been broken by his

opponent. In order to hide this, he had swallowed all of them. [Aelianus,

Miscellaneous History (

Eurydamas from Cyrene won a

pugilist contest, but all his teeth had meantime been broken by his

opponent. In order to hide this, he had swallowed all of them. [Aelianus,

Miscellaneous History ( The “Pancration” (=no

holds barred) was not

a marginal sport of the Olympics. In Olympia, the Pancration was

regarded as “the most beautiful of contests” and statues of those

barbaric athletes were made, honoring their bestiality. [Philostratos,

Images (

The “Pancration” (=no

holds barred) was not

a marginal sport of the Olympics. In Olympia, the Pancration was

regarded as “the most beautiful of contests” and statues of those

barbaric athletes were made, honoring their bestiality. [Philostratos,

Images (