THE EUCHARISTIC PRAYER. PART THREE

The opening part of the Eucharistic Prayer is a brief summary of the story of creation and salvation, a story that is told in greater detail in the corresponding part of the Liturgy of St Basil. After the people have joined the Seraphim in singing, and indeed ‘shouting’, ‘the triumphal hymn’, ‘Holy, holy, holy’, the prayer now focuses on how and why God, the All-Holy, brought about our salvation.

Seraph from an icon of the Dormition

The prayer takes as its starting point the wonderful words from St John’s Gospel, ‘This is how God loved the world: he gave his only-begotten Son, so that whoever believes in him might not perish, but have eternal life’. This is the natural meaning of the Greek, as well as of the ancient translations in Latin, Syriac and Coptic, but most English versions have something like, ‘God so loved the world’, which people usually take to mean ‘so much’, but this slightly misses the point. We do not know God’s nature. God is, as the opening of the prayer says, ‘ineffable, incomprehensible, invisible, inconceivable’. God is known to us by his acts, by what he does, and what St John is saying to us is, ‘If you want to know what God is like, look at what he does’. “God”, as I say in my First Letter, “is love”. And what does this mean? Do you want to know what God’s love is like? I’ll tell you, “This is how God loved the world”, he gave the most precious thing he had, his only Son’. Just as in the Old Testament God had asked Abraham to give him the most precious thing he had, his beloved, only son Isaac, and to slay him in sacrifice, so he himself gives his own beloved, only Son to be offered up, in the words of the Proskomide, to be ‘sacrificed for the life and salvation of the world’.

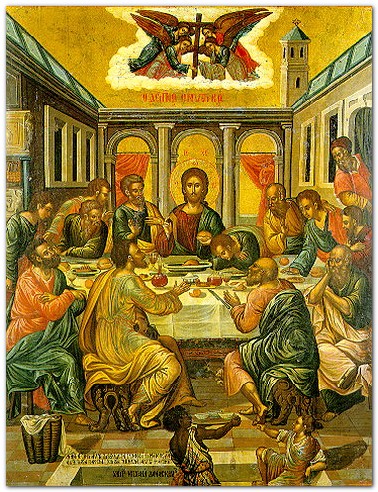

And so we reach the heart of the great prayer and the heart of the divine liturgy as we recall the Mystical Supper, the prelude to the Passion, Death and Resurrection of Our Lord. But we do more than simply remember these events, we ourselves truly take part in them ‘mystically’, or, as the Cherubic Hymn puts it, ‘in a mystery’. Just before Communion we shall say the prayer which begins, ‘Of your mystical Supper, Son of God, receive me today as a communicant’, and we believe that, by the power of God’s Spirit, the gifts of bread and wine that we have placed on the holy Table become the Body and Blood of Our Lord.

Icon from Mt Sinai

The priest relates what happened at the Last Supper in words that go back to the very earliest days of the Church, even before the Gospels were written. The earliest account that we have is the one given us by St Paul in his First Letter to the Corinthians, written only about twenty years after the Crucifixion. Here is what he writes, ‘For I received from the Lord what I also handed on to you, that the Lord Jesus, on the night he was handed over, took bread, and, after he had given thanks, broke it and said, “Take eat. This is my body that is broken for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” In the same way also the cup, after supper, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.” For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes. Therefore whoever eats this bread or drinks the Lord’s cup unworthily will have to answer for the body and blood of the Lord’. St Paul plays on the meaning of the Greek word ðáñáäίäïíáé [paradidonai], which means ‘hand over’, ‘hand on’, and hence also, but not very commonly, ‘betray’. ‘Tradition’ in Greek is ðáñάäïóéò [paradosis]. The usual words for ‘betray’ and ‘betrayer’ are ðñïäίäïíáé [prodidonai] and ðñïäόôçò [prodotes], a word used of Judas in the texts of Holy Week, but not in the Gospels. There is no word ðáñáäόôçò [paradotes] in Greek.

The text of the Liturgy has filled out the biblical texts of this account. In the first place, it adds ‘or rather gave himself up’, in order to underline that Our Lord goes willingly to his death. If his Father showed how he loved the world by sending his only Son, the Son shows how he loves the world by giving himself up to death. As Shakespeare didn’t say, ‘Love is not love, when it is not prepared to die for the beloved’. That is also the calling of the Christian, who is to ‘be perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect’.

Secondly, it adds that Our Lord took the bread ‘into his most pure and unblemished hands’. The Greek for ‘unblemished’ is ἀìùìήôïéò [amometois], which also means ‘blameless’, like its synonym ἄìùìïò [amomos]. This is the word used throughout the Old Testament to describe animals that are acceptable for sacrifice. They must be perfect, without spot or blemish. In the Proskomide, as the priest makes the second cut into the prosphora, he quotes from the prophet Isaias the words, ‘And as an unblemished [amomos] lamb before its shearer is dumb’. By using this word, which is not in Isaias here, we are reminded, in the words of the prayer before the Cherubic Hymn, that Christ is the one ‘who offers and is offered, who receives and is distributed’.

Finally all accounts of the Last Supper in the New Testament say either that Our Lord ‘gave thanks’, or that he ‘blessed’ the bread. The traditional Jewish blessing over bread is, ‘Blessed are you, Lord, our God, King of the universe, who brings forth bread from earth’. The blessing our Lord would have used was probably very similar. The first Eucharist then began with ‘thanksgiving’, or åὐ÷áñéóôίá.