Abbess of Folkestone (†640)

Source:

https://www.oca.org/saints/lives/2019/08/31/102446-saint-eanswythe-abbess-of-folkestone

| Orthodox Outlet for Dogmatic Enquiries | Biographies |

|---|

|

Saint Eanswythe, Abbess of Folkestone (†640)

Source:

https://www.oca.org/saints/lives/2019/08/31/102446-saint-eanswythe-abbess-of-folkestone |

A first approach to the indigenous Orthodox Saints and Martyrs of the Ancient Church who lived and who propagated the Faith in the British Isles and Ireland during the first millennium of Christianity and prior to the Great Schism is being attempted in our website in our desire to inform our readers, who may not be aware of the history, the labours or the martyrdom of this host of Orthodox Saints of the original One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church of our Lord.

"The Church in The British Isles will only begin to grow when she begins to venerate her own Saints" (Saint Arsenios of Paros †1877)

|

Saint Eanswythe was born around 614, the only daughter of King Eadbald of Kent and his wife Emma, who was a Frankish princess. At the time of Eanswythe’s birth, her father was probably a pagan, while her mother was almost certainly a Christian. Therefore, it is highly likely that Eanswythe was baptized and raised as a Christian.

When she was two

years old, her paternal grandfather King Ethelbert of Kent

(February 25) died. Saint Ethelbert had been baptized at Saint

Martin’s church in Canterbury by Saint Augustine of Canterbury

(May 28). It was Saint Augustine who came to England in 597 with

several monks in order to re-establish Christianity, which had

almost been wiped out by the pagan Anglo-Saxons. These monks

carried out their missionary work under the protection of King

Ethelbert.

Eanswythe’s

father King Eadbald offered no opposition to Christianity while

his father was alive. When Saint Ethelbert died, however,

Eadbald’s attitude changed. Not only did he embrace idolatry, he

also married his father’s second wife (Bede, ECCLESIASTICAL

HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH PEOPLE Book 2, ch. 1). While this

practice was prohibited by Church law, it was quite common among

the pagan royalty.

About this time,

King Sabert of the East Saxons (and a convert to Christianity)

passed away. His three sons were pagans, and so idolatry

returned to that territory as well.

Saint Laurence of

Canterbury (February 3), Saint Mellitus of London (April 24),

and Saint Justus of Rochester (November 10) held a council to

determine what they should do. They decided that they should not

waste their time among the pagans, and to go where people would

be more receptive to their preaching. Appalled by the King’s

behavior and by the rise of paganism, Saints Mellitus and Justus

went to Gaul.

The night before

he was to leave Canterbury, Saint Laurence decided to sleep in

the church of Saints Peter and Paul. Saint Peter appeared to him

and rebuked him for even thinking of leaving his flock. He also

beat Saint Laurence, who remained with his flock and even

converted King Eadbald.

The king ended

his unlawful marriage and was baptized. Within a year, Saint

Justus returned to Rochester. The people of London, who lived in

the realm of the East Saxons, refused to accept Saint Mellitus

back to his See. Following the death of Saint Laurence in 619,

Saint Mellitus succeeded him as Archbishop of Canterbury.

From her

childhood, Saint Eanswythe showed little interest in worldly

pursuits, for she desired to dedicate her virginity to God and

to serve Him as a nun. Her father, on the other hand, wanted her

to marry. Saint Eanswythe told him that she would not have any

earthly suitor whose love for her might also be mixed with

dislike. There was a high rate of mortality for children in

those days, so she knew it was likely that at least some of hers

would also die. All of these sorrows awaited her if she obeyed

her father. The young princess told her father that she had

chosen an immortal Bridegroom Who would give her unceasing love

and joy, and to Whom she had dedicated herself. She went on to

say that she had chosen the good portion (Luke 10:42), and she

asked her father to build her a cell where she might pray.

The king

ultimately gave in to his daughter, and built her a monastery in

Folkestone in Kent. While the monastery was under construction,

a pagan prince came to Kent seeking to marry Eanswythe. King

Eadbald, whose sister Saint Ethelburga (April 5) married the

pagan King Edwin (October 12) two or three years before,

recalled that this wedding resulted in Edwin’s conversion.

Perhaps he hoped that something similar would happen if

Eanswythe married the Northumbrian prince. Eanswythe, however,

insisted that she would not exchange heavenly blessings for the

things of this world, nor would she accept the fleeting joys of

this life in place of eternal bliss.

Around the year

630, the building of the monastery was completed. This was the

first women’s monastery to be founded in England. Saint

Eanswythe lived there with her companions in the monastic life,

and they may have been guided by some of the Roman monks who had

come to England with Saint Augustine in 597.

Saint Eanswythe

was not made abbess at this time, for she was only sixteen years

old. We do not know of any other abbess before Saint Eanswythe,

but a few experienced nuns may have been sent from Europe to

teach the others the monastic way of life. A temporary Superior

could have been appointed until the nuns were able to elect

their own abbess.

There are many

stories of Saint Eanswythe’s miracles before and after her

death. Among other things, she gave sight to a blind man, and

cast out a demon from one who had been possessed.

We know few

details about the rest of Saint Eanswythe’s life. Following the

monastic Rule, she prayed to God day and night. When she was not

in church, she spent her waking hours reading spiritual books

and in manual labor. This may have consisted of copying and

binding manuscripts. The nuns probably wove cloth for their

clothing, and also for church vestments. They cared for the sick

and aged nuns of their own community, as well as for the poor

and infirm from outside. Then there was the daily routine of

cooking and cleaning.

According to

Tradition, Saint Eanswythe fell asleep in the Lord on the last

day of August 640 when she was only in her mid-twenties. Her

father King Eadbald also died in the same year.

The monastery at

Folkestone did not last very long after the saint’s death. Some

say it was destroyed by the sea, while others say it was sacked

by the Danes in 867. Saint Eanswythe’s holy relics were moved to

the nearby church of Saints Peter and Paul, which was farther

away from the sea. In 927 King Athelstan granted the land where

the monastery had stood to the monks of Christchurch,

Canterbury.

As time passed,

the sea continued to encroach on the land. In 1138 a new

monastery and church, dedicated to Saint Mary and Saint

Eanswythe, were built farther inland. The relics of Saint

Eanswythe were transferred once again, this time from the church

of Saints Peter and Paul to the new priory church. During the

Middle Ages, this second transfer of her relics was celebrated

on September 12, which is the present Feast Day of the church of

Saint Mary and Saint Eanswythe.

On November 15,

1535 the priory was seized by the officers of the King, who

plundered the church of its valuables. The shrine of Saint

Eanswythe was destroyed, but her relics had been hidden to

protect them.

On June 17, 1885

workmen in the church discovered a niche in the walls which had

been plastered up. Removing the plaster, they found a reliquary

made of lead, about fourteen inches long, nine inches wide, and

eight inches high. Judging by the ornamentation on the

reliquary, it dated from the twelfth century. A number of bones

were found inside, which experts said were those of a young

woman. Today the niche is lined with alabaster, and is covered

by a brass door and a grille.

At first, the

holy relics were brought out for veneration every year on the

parish Feast Day. This practice ended when several parishioners

accused the Vicar of “worshiping” the relics. Although Saint

Eanswythe’s relics are no longer offered for public veneration,

candles and flowers are sometimes placed before the brass door

where they are immured.

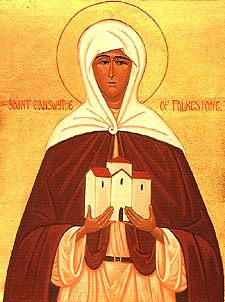

An Orthodox

iconographer has presented the parish of Saint Mary and Saint

Eanswythe with an icon of the saint.

|

Article published in English on: 7-3-2020.

Last update: 7-3-2020.