|

Orthodox Outlet for Dogmatic Enquiries | British & Celtic Orthodoxy |

|---|

|

7th Century England Was Orthodox Christian:

By:

Archpriest Vladislav Tsypin

-

OrthoChristian

|

|

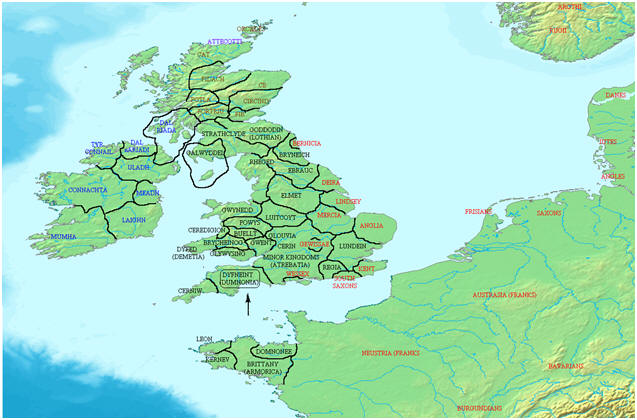

In the seventh century A.D., the population of Britain consisted

mainly of two ethnic groups relatively equal in number, collectively

known as the Celts and the Anglo-Saxons respectively. The Celts can

be divided into three major sub-groups, namely the Welsh (the

descendants of the Britons—the native inhabitants of Britain who

were driven west by the invading Angles and Saxons) in Wales; the

Picts (an indigenous tribal confederation of peoples in Scotland);

and the Fenians, or Scots (a Gaelic people that migrated from

Ireland to Scotland around the late fifth century)—this is how they

were commonly called in Britain (“Scotti”, meaning “wanderers”,

referred to the Irish in general). The name “Scotland” derives from

the Latin “Scotia”—“the land of the Scots”. This is because in the

middle ages, Scotland as a country was developed by the Scots rather

than the native Picts.

Dalriada

The territory of Dalriada in its heyday, the 590s.

In the fifth century the Fenians changed their name and began to be

called Gaels; they founded the kingdom of Dalriada (also spelled Dal

Riata) north of the Antonine Wall, the territory of which extended

to northeastern Ireland

(Ulster) and groups of small islands between Britain and Ireland. By

the beginning of the seventh century Dalriada had become an

overwhelmingly Christian state, and the Irish Celtic rites were

established in it. The liturgical traditions and practices of the

Celtic Church were slightly different from those of the Roman

Church. Their main theological dispute of that time was the

controversy over the correct date for Pascha (the “Roman party” in

Britain was represented by disciples of St. Augustine of Canterbury,

the Roman enlightener of the Anglo-Saxons). The greatest and more

significant ecclesiological and canonical difference was the Church

administration. In Celtic Christianity all authority belonged to

abbots of monasteries, while bishops had no administrative

power—they lived at the monasteries, obeyed their abbots, and

performed their sacramental functions, including ordinations.

The founders of monasteries in Ireland and Dalriada were held in

great honor, and thus the abbots were often referred to as “comarbae”

(meaning “heirs”, “successors” in Old Irish). Every abbot of Iona in

Scotland was called “comarba Colum Cille” (“successor of Columba”),

and every abbot of Armagh was called “comarba Patraic” (“successor

of Patrick”). In the second half of the seventh century, the most

influential abbot in Dalriada, Ireland and even Northumbria in

northern England was St.

Adomnan,

the ninth successor of St.

Columba and

the author of the most famous version of his (Columba’s) Life. In

688, under the influence of Northumbrian monks, St. Adomnan

introduced the Roman paschalia in the churches of Dalriada, though

the brethren of Iona refused to adopt it.

Pictland

The Synod of Whitby

The largest ethnic group in Caledonia (the Roman name for Scotland)

were the Picts. They inhabited most of its territory, and by the

beginning of the seventh century the majority of them had become

Christians. They converted to Christianity mainly thanks to the

apostolic labors of St. Columba, who made numerous missionary

journeys to their land in the second half of the sixth century. At

the turn of the sixth century, Pictland already had a number of

monasteries founded by St. Columba and his disciples, although most

of the settlements where they were situated cannot be identified

today. However, we have no information about the bishops who were

sent to serve in Pictland, so we presume that the Church throughout

the kingdom was administrated from by the abbots of Iona, where

bishops actually lived.

The liturgical traditions of the Church of Pictland were identical

to those of the Churches in Ireland and Dalriada. But in 663/664,

the famous Synod of Whitby was summoned in Northumbria, gathering

the proponents of both the Celtic and the Roman customs. At the

Synod, St. Colman of Lindisfarne supported the “Celtic party”, while

St. Wilfrid of York and Hexham supported the “Roman party” with its

paschalia. After a dispute between Sts. Colman and Wilfrid, the

Roman party ultimately won the day. After St. Wilfrid’s consecration

as bishop of Eboracum (York), the churches of South Pictland, at

that time occupied by Northumbrians, were under his jurisdiction for

several years. At that time they used the Roman paschalia to

celebrate the Resurrection of Christ.

St. Columba's

miracle at the gate of King Brude's fortress.

In 681, the new Diocese of Abercorn was established in South

Pictland, close to the south coast of the Firth of Forth, to provide

spiritual guidance to the local population. St. Trumwine was

consecrated the first bishop of Abercorn. He made efforts to

introduce the Roman paschalia and other practices in all the

parishes of his bishopric, but after Northumbria’s defeat in the

Battle of Dun Nechtain in 685, St. Trumwine “withdrew with his

people who were in the monastery of Abercurnig [Abercorn], seated in

the country of the English, but close by the arm of the sea which

parts the lands of the English and the Scots. Having recommended his

followers, wheresoever he could, to his friends in the monasteries,

he chose his own place of residence in the monastery, which we have

so often mentioned, of men and women servants of God, at

Streaneshalch [Whitby].”1 He

reposed there many years later, unable to give spiritual guidance to

the Church of Pictland, which, therefore, reverted to its Celtic

practices and upheld them for a quarter of a century after him.

Wales

Wales in our days.

The most numerous Celtic people in seventh century Britain were the

Britons, or Cymry, who were brutally massacred in great numbers by

the invading Angles and Saxons and pushed from their native lands.

Resisting the aggression, the Celtic tribes remained safe in the

west from Anglo-Saxon domination and formed small British kingdoms

in Cornwall (Dumnonia), Wales (originally called Cymru, or Cambria)

and Strathclyde (or Cumbria), which stretched to the southwest of

Scotland. Though a distinct entity, Wales (the largest of these) was

not a monolithic state. It was divided into several small

independent kingdoms which acted in alliance with each other. Among

them were Gwynedd (NW Wales), Dyfed (SW Wales), and Powys (E Wales).

The seventh century, like the previous sixth century, was marked by

the Celtic Britons’ stout resistance to the Anglo-Saxons’ steady

onslaught. They experienced both victories and defeats in this

struggle. Yet one of the battles proved fatal for Cambria. It was

the Battle of Legacastir [the Roman name of present-day Chester]

which took place in about 616. In it the joint army of Powys and

several smaller allied kingdoms fought against the Northumbrians.

However, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle dates this battle to 604. The

Chronicle’s entry for 607 reads: “Ethelfrith led his army to

Legacastir; where he slew an innumerable host of the Welsh; and so

was fulfilled the prophecy of St. Augustine, wherein he saith ‘If

the Welsh will not have peace with us, they shall perish at the

hands of the Saxons.’”2

St. Bede of Jarrow,

giving his account of the Battle of Legacastir, refers to the

British soldiers and priests who came with them as “heretics” only

because of their way of calculating the date of Pascha and other

minor liturgical differences: “Their priests … came together to

offer up their prayers to God for the soldiers, standing apart in a

place of more safety. Most of them were of the monastery of Bangor,

in which, it is reported, there was so great a number of monks, that

the monastery being divided into seven parts, with a ruler over

each, none of those parts contained less than three hundred men, who

all lived by the labor of their hands. Many of these, having

observed a fast of three days, resorted among others to pray at the

aforesaid battle, having one Brocmail appointed for their protector,

to defend them whilst they were intent upon their prayers, against

the swords of the barbarians. King Ethelfrith being informed of the

occasion of their coming, said, ‘If then they cry to their God

against us, in truth, though they do not bear arms, yet they fight

against us, because they oppose us by their prayers.’”3

The Venerable Bede.

Thus, in modern legal language, the King of Northumbria refused to

recognize these priests as noncombatants. We read further: “He,

therefore, commanded them to be attacked first, and then destroyed

the rest of the impious army, not without considerable loss of his

own.”4

Here St. Bede’s Anglo-Saxon patriotism and religious intolerance go

over the top… For him the “impious army” was not the horde of the

pagan Angles but the army of the Christian Britons, though the only

major difference between the Celtic and the Roman traditions (St.

Bede belonged to the latter) was in the way the two Churches

calculated the date of Pascha and tonsured monks. “About twelve

hundred of those that came to pray are said to have been killed, and

only fifty to have escaped by flight. Brocmail turning his back with

his men, at the first approach of the enemy, left those whom he

ought to have defended, unarmed and exposed to the swords of the

enemies.”5 And

St. Bede concludes that account, gloating over their defeat: “Those

perfidious men… had despised the offer of eternal salvation.”6 Interestingly,

elsewhere in his wonderful book St. Bede displays a much more

tolerant attitude towards other Celts, namely the Scots (the Irish)

and the Picts. Perhaps he felt a personal antipathy to the Britons

about which we know nothing. By the way, the Angles and Saxons

contemptuously called the Britons “the Welsh”, meaning simply

“foreigners” [though, in effect, they themselves were foreigners!

Hence “Wales” means “the land of the foreigners”, and “Cornwall”,

originally “Corn-Wales”, means “the horn”, or “promontory, inhabited

by the foreigners.”—Trans.]. The victory in the Battle of Legacastir

gave Northumbria easy access to the Irish Sea and so the Celtic

world of Britain was then largely disintegrated: Cambria (Wales) and

Cumbria (or Hen Ogledd, meaning “the old north”) were thus separated

from each other.

Though attacks of the Angles and Saxons continued, the Britons did

manage to regroup in the west of the island. In some cases they took

advantage of the feud between some Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Thus, King

Cadwallon of Gwynedd, in alliance with the pagan King Penda of

Mercia (sealed by Cadwallon's marriage to Penda's sister, Alcfrith,

according to later sources) attacked Northumbria, which then was

ruled by St. Edwin, who had converted to Christianity. Earlier

Cadwallon and St. Edwin had been friends, but after Edwin’s return

to his homeland and succession to the Northumbrian throne their

friendship changed into hostility. So the Britons of Gwynedd took

advantage of the feuds between some Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in order to

regain independence and get even with the Angles of Northumbria,

their “age-old enemies”. In about 630, the joint armies of Gwynedd

and Mercia defeated the Northumbrians in the Battle of Cefn Digoll

(near present-day Welshpool). But the Battle of Hatfield Chase that

took place on October 12 (some give October 14), 633, was a

significant turning point in the struggle between the Britons and

the Anglo-Saxons.

According to St. Bede: “A great battle being fought in the plain

that is called Heathfield, Edwin was killed on the 12th of October,

in the year of our Lord 633, being then forty-seven years of age,

and all his army was either slain or dispersed. In the same war

also, before him, fell Osfrid, one of his sons, a warlike youth.”7 Thereupon,

according to St. Bede, though he may have exaggerated as he was very

much biased against the Britons, “a great slaughter was made in the

church or nation of the Northumbrians; and the more so because one

of the commanders, by whom it was made, was a pagan, and the other a

barbarian, more cruel than a pagan; for Penda, with all the nation

of the Mercians, was an idolater, and a stranger to the name of

Christ; but Cadwallon, though he bore the name and professed himself

a Christian, was so barbarous in his disposition and behavior, that

he neither spared the female sex, nor the innocent age of children,

but with savage cruelty put them to tormenting deaths, ravaging all

their country for a long time, and resolving to cut off all the race

of the English within the borders of Britain.”8 However,

before that time it was the Angles and Saxons that had been

slaughtering the Celtic Britons living in Britain for a long time,

literally striving to exterminate them. Therefore, by cruelly

murdering inhabitants of Northumbria the Britons were trying to

wreak vengeance on their oppressors. This hostility was largely

explained by the fact that the Angles and Saxons on converting to

Christianity regarded the native Britons as “heretics” on account of

their controversy over the proper calculation of Pascha, whereas,

according to St. Bede, “it being to this day the custom of the

Britons not to pay any respect to the faith and religion of the

English, nor to correspond with them any more than with pagans.”9

Soon after that, Cadwallon fell in battle with the army of Angles

under St. Oswald. On returning from Dalriada where he had been in

exile, St. Oswald with his small army attacked King Cadwallon’s band

at Cad-ys-Gual (“Heavenfield” in English). The

battle resulted in a decisive victory for St. Oswald, and Cadwallon

was defeated and killed. Now the territories that Gwynedd had won

back from Northumbria were lost. Thenceforth Mercia (with which it

had allied not long before) not Northumbria posed a major threat to

the kingdom of Gwynedd.

In 634, following the mentioned battle, the throne of Gwynedd was

seized by Cadfael ap Cynfeddw (that is, “Cadfael, son of Cynfeddw),

while Cadwallon’s one-year-old son St. Cadwaladr Fendigaid was

hidden for a time. About 655, St. Cadwaladr at last ascended the

throne of Gwynedd. He was loved as a pious, peaceful ruler, and

before his death he took monastic vows. St. Cadwaladr died during

the devastating plague of 664 [although, according to the majority

of sources, this saint died of another terrible plague that swept

the country eighteen years later, in 682.—Trans.) and was canonized

after his death.

St. David,

Archbishop of Mynyw.

The period between the fifth and the eighth centuries was called

“the age of saints” in Wales. The most venerated saint of the Welsh

land is its patron saint—St.

David, Archbishop of Mynyw (Menevia).

His feast day, March 1 (he is venerated in Orthodoxy on March 14),

is still a national holiday in Wales. He was a champion of the

Orthodox faith, a missionary, founder of a large number of

monasteries in different parts of Britain and even in Brittany. His

principal monastery of Mynyw (now St. Davids in Pembrokeshire)

became his archbishopric as well. St. David introduced a very strict

rule at his monastery. Manual labor was compulsory and always

flourished there. Any conversations, except for very necessary ones,

were forbidden. The brethren were not allowed to use horses or oxen

in plowing, so they would always drag the plow through their fields

themselves, while practicing unceasing prayer. The food of the

brethren consisted of bread, vegetables and water. Meat and milk

products, alcohol and even fish were excluded. St. David was often

referred to as “aquaticus” (“water-man”) because he lived

exclusively on bread and water. According to one version, St. David

reposed in 589, and according to another version, it was in 601.

Among those who followed in St. David’s footsteps in the seventh

century was St.

Beuno.

He was born in the kingdom of Powys and was related to the royal

family. Driven by love for God and an intense desire to dedicate his

life to the service of Christ, St. Beuno as a very young man joined

Bangor Monastery, which had been founded by St.

Deiniol.

It was there that he received the tonsure and was ordained. Later he

was sent to found new monasteries in the kingdom of Gwynedd. About

the year 616 the saint established a monastery at Clynnog Fawr.

After that, following the tradition of the Celtic saints, Beuno

undertook numerous missionary journeys across Wales and some early

English kingdoms. In Wales he built around ten monasteries, which

became seedbeds of holy monks and ascetics in the Celtic tradition.

Among the monastic communities established by this saint of God were

those at Llanfeuno and Llanymynech. “Ancient traditions say that St.

Beuno, as a wandering preacher, used to pay visits to the monastic

islands in Wales at Bardsey and Anglesey. On Anglesey he may have

founded a church, or, most likely, a monastery, in a place called

Aberffraw… St. Beuno for some time led a solitary ascetic life in

Somerset in southwest England, where a tiny and lovely church in

Culbone—which stands to this day—served as his a cell. This is the

smallest active parish church in all England. It is dedicated to St.

Beuno… Culbone church is located in a very quiet and remote place

right beside the Bristol Channel, surrounded by forest… This is a

typical setting for the ancient Celtic saints.”10 The

Venerable Beuno reposed about 640 at his monastery of Clynnog Fawr

and was interred there. A great number of miracles occurred at his

holy relics. The saint became a special patron of sick children.

Veneration for St. Beuno was so strong that it continued after the

disastrous Reformation, when the veneration of saints was officially

prohibited all over Britain. Thus, even in the Protestant Wales,

“children who suffered from many diseases were brought and led to

the holy well, bathed in it and left for a night inside the chapel

on the grave or near the grave of the holy man Beuno; and many of

them were miraculously cured.”11

St. Winifred,

St. Beuno’s niece, had an Anglo-Saxon name and was probably of mixed

origin. In her youth the saint wished to become a nun and took

monastic vows. Little reliable information about her life survives,

but, according to the most popular tradition, one Welsh prince was

stricken with the desire to have her in marriage. Since the saint

was determined to preserve her virginity and lead a monastic life,

the prince decided to take her by force. Winifred refused his

advances, and he struck off her head on the spot. A healing spring

gushed forth where her head had fallen. That place was called

Trefynnon in Welsh and Holywell in English. According to tradition,

through the prayers of St. Beuno his holy niece came back to life.

Winefred then returned to Gwytherin (where she had taken the veil),

established a convent there, and became its abbess. The holy maiden

reposed in about 660. In time her holy relics were translated to

Shrewsbury Abbey (now in county Shropshire, western England), where

countless miracles occurred through her intercessions. Both

Shrewsbury Abbey and the holy well at Trefynnon remained great

pilgrimage centers throughout the middle ages.

The Venerable

Melangell of Wales.

Another celebrated saint of seventh century Wales is the Venerable Melangell.

Born in Ireland, she sailed to Wales where she lived as an anchoress

in solitude amid dense forests of Powys for fifteen years. One day

King Brochwel Ysgithrog during a hunting trip came upon a clearing

in which a beautiful maiden was standing deep in prayer. According

to the Life of St. Melangell, “a hare that was being pursued by the

hounds was lying beside the holy woman and facing the dogs down

boldly. The hounds submissively ran aside and stopped, unable to

move.”12 Amazed

by the piety of the anchoress, Brochwel donated a parcel of land to

be used by her to found a convent. In due course the maiden of God

founded a community of nuns, became its first abbess, and ruled it

until her death.

Another notable figure of “the age of saints” in Wales is St.

Tysilio,

a son of the aforementioned King Brochwel, to whom the Welsh

chronicle of kings is also attributed. As a very young man Prince

Tysilio went to study at the monastery of Meifod, where his

spiritual mentor was the holy hermit and abbot Gwydfarch. After

that, Tysilio lived for seven years on an islet near the Island of

Anglesey in the Menai Straits (a channel separating Anglesey from

the mainland of NW Wales). This isle was later called Ynys Dysilio

(“St. Tysilio’s Island”) after him. On his return to Meifod, St.

Tysilio became its abbot and afterwards established a number of

other monasteries in various parts of Wales—for example, in Clwyd,

Cardiganshire, and Dyfed.

However, the man of God could not avoid temptation. When St.

Tysilio’s brother died, his widow wished to marry him and make him

the King of Powys. The holy man turned down both proposals, and so

for political reasons soon Meifod Monastery was persecuted by the

royal family. Then St. Tysilio resolved to leave his homeland. Thus,

taking a small group of monks with him, the saint embarked for

Brittany, where he eventually founded the monastery of St. Suliac in

617 and became its first abbot. St. Tysilio reposed at St. Suliac in

about 640.13 Witnesses to the Church life and ascetic labors of a cloud of saints in Wales during its period of independence are the surviving ruins of early churches, church enclosures and monastic cells, ancient cemeteries with early gravestones, stones with ogham and Latin inscriptions (which had been erected at crossroads and later remained in their locations or moved to museums), and holy wells that have been venerated by pious people since time immemorial.

The Church structure,

liturgical rites, specifics of piety, Christian customs and everyday traditions

of Wales had much in common with those of another Celtic country—namely,

Ireland. And in many ways, all of them made this far western corner of the

Christian world very close to the Christian East

|

File created: 8-12-2019.

File revised: 8-12-2019.