| Orthodox Outlet for Dogmatic Enquiries | Dogmatics |

|

Mortalists, Mortalism

Origin and evolution of the heresy

By

Paul

D.

Vasiliades

Source: Paul D. Vasiliades,

ÌÏ×Å

Vol.8, pp. 363, 364 |

|

Heretical

nickname, which first appeared in the 8th century in a work by

Saint John of Damascus. It specifically mentions that

“mortalists” were “those who initiated the claim that the human

soul is alike to that of the beasts, and that it perishes along

with the body.”

(On Absolutions 90, PG 94: 757B). Obviously the key elements of this non-Orthodox belief referred to (a) similitude of human souls to the souls of animals and (b) simultaneous elimination of the soul upon the death of the body.

While John the Damascene makes no reference to

the place and time of this anthropological dogmatic deviation,

Eusebius of Caesarea (early 4th c.), using similar phraseology

mentions the Christians of Arabia who during the 3rd century AD

held a similar dogma “alien to the doctrine of the truth”.

Specifically, they maintained that: “About the same time,

others arose in Arabia, putting forward a doctrine foreign to

the truth. They said that

during the present time the human soul dies and deteriorates

together with the body, but that at the time of the resurrection

they will once again be alive together. “

(Ecclesiastical History 6:37, PG 20:59: 29). -299).

Origen's determining intervention was needed (as

was the case with the refutation of the views by the gnostic

Christian Heracleon in “Exegetics on the Gospel of John 13:60,

61; here, Origen also accepts a kind of “mortalism”, by stating

that “we too shall say so (that the soul is mortal)”, in order

to reject these obviously of Jewish origin ideas, which had at

their core the biblical setting of man as a living soul (Hebr.

Nefes), as a uniform entity.

The ecclesiastic historian Nikiforos Kallistos

Xanthopoulos (early 14th century) mentions that they had

suggested “the human soul is simultaneously with the body, and

that it too dies temporarily along with it and undergoes

deterioration, and later, during the resurrection, it relives

anew, both with its own along with the other bodies, thereafter

to be preserved incorruptible.” (Ecclesiastic history 5:23, PG

145: 11120, cmp Nikitas Choniatis, Dogmatic armor 40, PG 139:

13410/65 [J. Van Dieten (1970) 50-59' “Mortalists” ]).

The earliest description by Eusebius as well as

the descriptions by the other historians, who basically follow

him, further state that at the resurrection of the dead a) the

human soul will come back to life with its body and b) that

incorruptibility will then be made possible. Despite the mention

that this doctrine was 'introduced' among the Christians of that

time, evidence rather shows that the immortality of the soul was

not the dominant perception among Christians in general until

the 2nd century – a condition that gradually changed in the

following generations with the incorporation of Platonic

interpretive preconditions (Florovsky, p. 91. Jaeger, p. 146).

Early writers such as Justin Martyr, Tatian, Theophilos of

Antioch, Irenaeus of Lyons [*]

and Arnobius denied the natural immortality of the soul and

referred to some kind of extinction of the soul during natural

death. Modern research has shown that the positions in the works

of authors such as Elder Efstratios of Constantinople (late 6th

century), John the Deacon (11th century), Nikitas Stethatos (mid

11th century), Philip Monotropos (early 12th c.) And Michael

Glykas (12th c.) comprised the continuation of those early

views, enriched with new elements such as the Neoplatonic

interest in Platonic oblivion (Constas, p. 110).

The matter was examined with renewed interest

during the Reformation and especially by Calvin in 1534

(published 1542) in his first theological work “Psychopannychia”,

in which he condemned the anabaptist notion of “sleep” (in

reality death) of the soul in the space between Death until the

resurrection and maintained that the souls of the faithful after

their death remain in peaceful expectation, but always in an

unbroken and conscious communion with Christ. Mortalism was a

major current within English Protestantism in the 17th century,

with John Milton, Thomas Hobbes, and Isaac Newton as its

prominent supporters. Already in the 15th c. the Socinians and

in the 16th c. the Anabaptists had adopted similar biblical

interpretations of the inherently mortal soul, while similar

were the positions of the Millerites and Jehovah's Witnesses in

the 19th century. It seems the relative perceptions regarding death, sleep or elimination of the soul could be distinguished into three basic categories of Christian “mortalism”: a) the view of death as “sleep” of the soul (constant vigil of the soul, hypnopsychosis), which, like the traditional view of the soul, presupposes the immortality of the immaterial soul, according to which the soul continues to live unconsciously and remains inert (“inactive”, “idle”) or “sleeps” until the resurrection; b) the broad view of mortality - which presupposes that the soul is the “nous” (mind) or more commonly, the entire living man, who exists as a result of the union of breath (or spirit) and body and not an immortal substance - maintains that the soul at death ceases to exist and that it sleeps only metaphorically, awaiting the resurrection; and

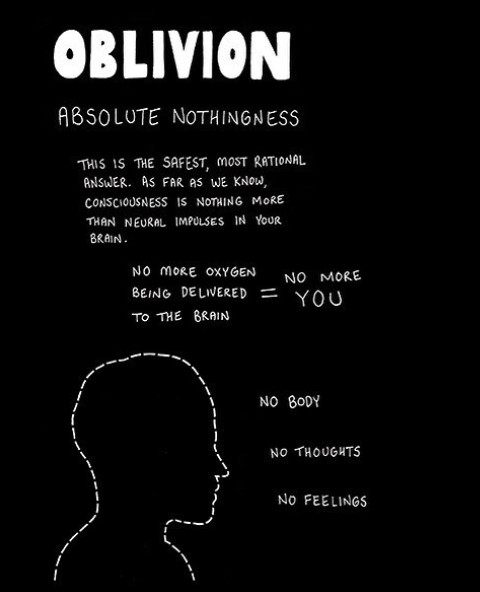

c) in contrast to the two previous categories,

which include the belief in the general immortality of souls

also after the resurrection, there is a special form of

mortalism, according to which, after the final Judgment, the

souls of the condemned will vanish, or otherwise, will be

annihilated forever. The last two views, by regarding that the

human soul is inherently mortal, allow divine grace to either

bestow eternal life or immortality accordingly - usually

described as immortality by Grace.

Outside the Christian context, “mortalists” are described in the

12th century by Ioannis Tzetzis [Book of History (Thousands)

180:222). Examples: Homer:

“...whereas the soul of

man can neither return nor be abducted, once it has passed

through the wall of teeth (the physical body)...” (Odyssey 10,

v.408), also Aeschylus: “But when the dust has swallowed a man’s

blood, once dead, there is no resurrecting him then.” [Eumenides,

p. 647]).

As an accusation, the reproach of “mortalist” had

serious consequences in life and career, even up to recent

centuries, as evident for example in the condemnations of the

Byzantine philosopher John Italus (1082) and the Trabzon scholar

Sevastos Kyminitis (1682). The signification of mortalist/mortalism

by Adamantios Korais (Atakta, 1832, vol. 4, p. 174) as simply

“one who denies the resurrection of the dead” - by which

essentially is invalidated every form of the fundamental

biblical teaching about the resurrection - records the

simplification undergone by the term in common usage, which in

fact embraces a variety of meanings and interpretations that

preoccupied the broader Christian anthropology and eschatology

for centuries. P. Va.

OODE NOTES

*

This reference, (at least to Saint Irenaeus of

Lyon) as a mortalist does not apply, as in his works there is

the acceptance of souls waiting in Hades, but also clearly, the

by-Grace preservation of souls by God.

A) For example Saint Irenaeus writes: “And

this is why he said, “The Lord descended to Hades, evangelizing

His coming also to them, and granting the remission of sins to

those who believe in Him. But all who had hoped in Him had also

believed. That is, those who had pre-announced His Coming and

had served within His Providence: the righteous and the Prophets

and the Patriarchs.” (“Monitoring ...”, Book 4, ch.26:2).

B) More precisely, Saint Irenaeus had said the

following about the soul:

“1. The Lord had however quite fully taught that

souls not only continue to exist and do not go from body to

body, but that they also preserve the bodily character to which

they were joined, and they remember the works they had done here

but had ceased doing. The Saint made mention of these

things, when He spoke of the rich man and poor Lazarus, who

was now resting in the bosom of Abraham. He mentioned how after

his own death the rich man had recognized poor Lazarus as well

as Abraham, and that both of them were in their designated

place; also that the rich man begged for Lazarus (who didn’t

even eat from the crumbs of the rich man’s table) to be sent to

him to relieve his agony, where Abraham had responded (who knew

everything, not only regarding Lazarus but also the rich man),

by commanding obedience to Moses and the Prophets to those who

did not wish to end up in that

state of “suffering” and to accept the preaching of

Christ, Who was going to be raised from the dead. With these,

it became very clear that souls both continue to exist and that

they do not pass from body to body, but continue to have the

physical human image, so that they would be recognizable after

death, and would remember how things were here; also evident

was that Abraham had the prophetic gift and that every person

ends up living the way they deserve, it even before the onset of

Judgment Day. 2. However, some say that souls which had began to exist only recently cannot continue to exist for a long time: they must either be unborn in order to be immortal, or, if they had received the principle of existence, then they die along with the body itself. Let them learn, then, that the One Who is without beginning and end, and Who is actually and always and in the same manner disposed, is only God, the Lord of all. But all things that originate from Him, all things that have taken place and continue to take place, have acquired the beginning of their existence, which is why all are inferior to the One Who fashioned them, as they are not unborn: they continue to exist, however, and are prolonged over the centuries, according to the will of God the Creator. Just as God had created them in the beginning, likewise He had given them existence thereafter.

3. The firmament of the sky above us, the sun,

the moon and the other stars and all their beauty had come into

existence (whereas they had not existed originally) and they

continue to exist for a long time, in accordance with the will

of God. If one were to

think similarly about the souls, the spirits, and generally

about everything that was created, they would not be wrong,

given that all things that exist have their initial creation,

but they continue to exist, for as long as God wants them to

exist. These views are also testified by the prophetic

spirit, when saying: “For He said, and they became; He

commanded, and they were created. He placed them to be forever

and forever unto the ages”.

Then the Saint says the

following about the saved man: “He asked You for life, and

You gave him longevity of days, unto the ages”, hinting

that the Father of all also grants them a sojourn forever and

ever. Life is not from us, nor from our nature, but is given by

the grace of God. This is why whoever preserves the gift of life

and gives thanks to the One who gave it, will receive the

“longevity of days, unto the ages”. But whoever rejects it and

appears ungrateful to the Creator after being created, and does

not acknowledge the One who created him, deprives himself of the

sojourn “forever and ever.” And that is why the Lord said to

those who were ungrateful towards Him: “If you do not

become faithful in something minor, who will give you something

major?” Which means that those who in the brief and

temporary life were ungrateful to God Who gave it to them, they

will justly not receive “the longevity of days, unto the

ages”...

4. But just as the body is soul-endowed, yet

itself is not a soul, only joined to the soul as long as God

wills; likewise, the soul itself is not life; it only

participates in the life provided to it by God. That is why the

prophet says about the first-fashioned man: “He became a

living soul”. We are taught that because of its

participation in life, the soul became a living thing: so that

the soul may be implied separately, and its life separately.

Subsequently, given that God bestows life and continuing

existence, it is possible that souls - which did not exist

previously - could eventually come into existence provided God

had willed them to exist, and to continue to exist. Because the

will of God must govern and dominate over everything; however,

everything must bow and submit themselves to Him and be

subservient to Him.

Enough has been said so far, regarding the creation and the

residence of the soul. (“Monitoring

...” Book 2nd LD).

Bibliography

Florovsky,

G.,

Themes of Orthodox Theology, Athens: Artos Zois 21989.

Barth, Karl, The Theology o f John Calvin,

Michigan/Cambridge: Eerdmans 1995. Burns, Nor., Christian mortalism from Tyndale ôï Milton, Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1972 . Constas, Nich., “Ôï Sleep, Perchance ôï Dream”: The Middle State of Souls in Patristic and Byzantine Literature", Dop 55 (2 0 0 1 ) 110, 111 [9 2 -1 2 4 ].

Gavin, Fr., "The Sleep

of the Soul in the Early Syriac Church", Jaos 4 0 (1 9 2 0 ) 1 0

3-120.

Henry, Nath., "Milton and Hobbes:

Mortalism and the intermediate state", Studies in Philology 48/2

(1951) 234-249.

|