If Moses had a copy

of today’s Hebrew Bible, he wouldn’t be able to read it.

Just imagine . . .

You discover a time

machine, you travel back to the year 1425 B.C.,

and you meet Moses face-to-face. You excitedly tote along your

favourite Hebrew/English interlinear Bible, complete with the

Masoretic text and its English translation. You look forward to

showing Moses his own writings in print, transported over three

thousand years in time.

To your surprise and

disappointment, Moses just shrugs at the text, and leers at you with

an odd look on his face. You show him the Ten Commandments, yet

Moses has no clue how to read it. He gladly acknowledges his

encounter with God on Mt. Sinai, but he says this text looks

nothing like what God wrote on those two stone tablets.

In desperation, you

focus on the most important word in the entire Old Testament. The

Tetragrammaton.

The all-holy four-letter name of God. YHWH. Surely Moses will

immediately recognize the Hebrew inscription for God’s name!

To your dismay,

Moses says this word is just as foreign as everything else you have

shown him. Moses writes the Lord’s name himself, hoping to teach you

the proper way to write it. This word, too, is four letters. But it

looks as foreign to you as your text looks to Moses.

You return home,

disappointed, but wiser. The next time someone gushes with

excitement about the “ancient Hebrew text”, and the ability to “read

the same words Moses wrote”, you don’t share their excitement. You

hold your peace, and you meditate on God’s awesome ability to

preserve His Truth from generation to generation, even

if He has not preserved the original text of Scripture.

Most of the Old

Testament scriptures were written in Paleo-Hebrew, or a closely

related derivative. Generally considered to be an offshoot of

ancient Phoenician script, Paleo-Hebrew represents the pen of David,

the script of Moses, and

perhaps even the Finger of God on the stone tablets of the Ten

Commandments.

Modern Hebrew, on

the other hand, is not quite so ancient. Israelites acquired this

new alphabet from Assyria (Persia), somewhere around the 6th-7th

century B.C. This was the same general time period as Israel’s

exile to Babylon . . . many centuries after most

of the Old Testament was written.

Initially, the Old

Testament Scriptures were exclusively written in Paleo-Hebrew.

Then, after borrowing the new alphabet from the Assyrians, the Jews

began transliterating large portions of Scripture into the newer

version.

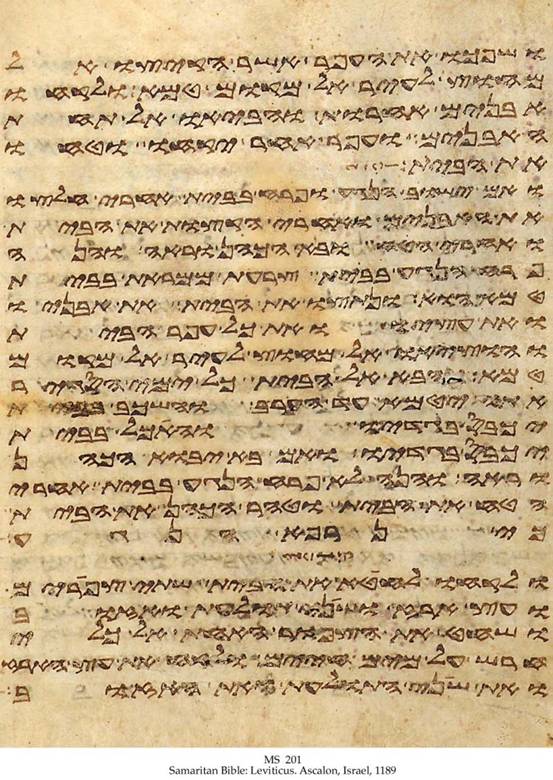

The

Samaritan Pentateuch uses the Samaritan alphabet, which is

closely related to Paleo-Hebrew. It is likely that much of

this text looks similar to what Moses and David saw in the

original copies of the Old Testament. The Masoretic Text

differs from the Samaritan Pentateuch in over 6,000 places.

But old habits die

hard. Especially with religion. Especially in regard to the name of

God. For a period of time, Jews transcribed the majority of the Old

Testament using the new Hebrew alphabet, while retaining the more

ancient way of writing God’s name. Thus, for a while, the Hebrew

Scriptures were written with a mixture of two different alphabets.

Even after the Jews began exclusively using the new Assyrian letters

to copy the text of Scripture, the more ancient Paleo-Hebrew letters

persisted in some corners of Jewish society. As late as the 2nd

century A.D., during the Bar

Kokhba revolt,

Jewish coins displayed writing with the ancient Paleo-Hebrew script.

~135

A.D. - This coin struck during the Bar Kokhba revolt

demonstrates usage of the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet in

the early 2nd century.

Eventually, though,

the newer Assyrian alphabet won the day. No new copies were being

made of the ancient text, and the earliest copies of Scripture

eventually disintegrated. By the time of Christ, the only existing

copies of the Old Testament had either been transliterated into

modern Hebrew, or translated into Greek (in the Septuagint). One

exception is the

Samaritan

Pentateuch,

which continues to be written in the ancient form, even to this day.

However, Jews and Christians both rejected the text as being of

questionable accuracy.

Today, many people

are under the false impression that the Masoretic Text represents

the “original Hebrew”, and that the Septuagint is less trustworthy

because it is “just a translation”. In fact, nothing could be

further from the truth. The Septuagint is actually

more faithful to the original Hebrew than the Masoretic

Text is. We no longer have

original copies of the Old Testament.

Nor do we have copies of the originals.

We now have copies

of the Scriptures transliterated into modern Hebrew, edited

by scribes,

compiled by the Masoretes in the 7th-11th centuries, and embellished

with modern vowel points which

did not exist in the original language. This

is what we now call the “Masoretic Text”.

We also have copies

of the Old Testament Scriptures which were translated into Greek,

over 1000 years

earlier than

the oldest existing Masoretic text. During New Testament times,

Jesus and the Apostles quoted from this Greek translation

frequently, and with full authority. They treated it as the Word of

God, and as a faithful translation. This is what we now call the

“Septuagint”.

Here is a sample

of the differences between

the Masoretic Text and the Septuagint.

While many

Protestant bibles rely heavily on the Masoretic Text, the Orthodox

Church has continued to use the Septuagint for the past 2000 years.

The Orthodox

Study Bible is

an English copy of the Scriptures, and its Old Testament is

translated from the Septuagint. It

is very good, and comes highly recommended!

I used to believe

the Masoretic

Text was

a perfect copy of the original Old Testament. I used to believe

that the Masoretic Text was how God divinely preserved the Hebrew

Scriptures throughout the ages.

I was wrong.

The oldest copies of

the Masoretic Text only date back to the 10th century, nearly 1000

years after the

time of Christ. And these texts differ from the originals in many

specific ways. The Masoretic text is named after the

Masoretes,

who were scribes and Torah scholars who worked in the middle-east

between the 7th and 11th centuries. The texts they received, and the

edits they provided, ensured that the modern Jewish texts would

manifest a notable departure from the original Hebrew Scriptures.

Historical research

reveals five significant ways in which the Masoretic Text is

different from the original Old Testament:

1.

The Masoretes admitted that they received

corrupted texts to begin with.

2.

The Masoretic Text is written with a radically

different alphabet than the original.

3.

The Masoretes added

vowel points which

did not exist in the original.

4.

The Masoretic Text excluded

several books from the Old Testament scriptures.

5.

The Masoretic Text includes changes

to prophecy and doctrine.

We will consider

each point in turn:

Receiving Corrupted Texts

Many people believe

that the ancient Hebrew text of Scripture was divinely preserved for

many centuries, and was ultimately recorded in what we now call the

“Masoretic Text”. But what did the Masoretes themselves believe?

Did they believe they were perfectly preserving the ancient text?

Did they even think they had received a

perfect text to begin with?

History says “no” .

. .

Scribal emendations – Tikkune Soferim

Early rabbinic

sources, from around 200 CE, mention several passages of Scripture

in which the conclusion is inevitable that the ancient reading must

have differed from that of the present text. . . . Rabbi Simon ben

Pazzi (3rd century) calls these readings “emendations of the

Scribes” (tikkune Soferim; Midrash Genesis Rabbah xlix. 7), assuming

that the Scribes actually made the changes. This view was adopted by

the later Midrash and by the majority of Masoretes.

In other words, the

Masorites themselves felt they had received a partly corrupted text.

A stream cannot rise

higher than its source. If the texts they started with

were corrupted, then even a perfect transmission

of those texts would only serve to preserve the mistakes.

Even if the Masoretes demonstrated great care when copying the

texts, their diligence would not bring about the correction of even

one error.

In addition to these intentional changes

by Hebrew scribes, there also appear to be a number of accidental changes

which they allowed to creep into the Hebrew text. For example,

consider Psalm 145 . . .

Psalm 145 is an

acrostic poem. Each line of the Psalm starts with a successive

letter of the Hebrew alphabet. Yet in the Masoretic Text, one of the

lines is completely missing:

Psalm 145 is an acrostic

psalm where each verse begins with the next letter of the

Hebrew alphabet. In the Aleppo Codex the first verse begins

with the letter aleph, the second with the beyt, the third

with the gimel, and so on. Verse 13 begins with the letter מ

(mem-top highlighted letter), the 13th letter of the Hebrew

alphabet; the next verse begins with the letter ס (samech-bottom

highlighted letter), the 15th letter of the Hebrew alphabet.

There is no verse beginning with the 14th letter נ (nun).

Yet the Septuagint (LXX)

Greek translation of the Old Testament does include

the missing verse. And when that verse is translated back into

Hebrew, it starts with the Hebrew letter נ

(nun) which was missing from the Masoretic Text.

In the early 20th

century, the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in caves near Qumran.

They revealed an ancient Hebrew textual tradition which differed

from the tradition preserved by the Masoretes. Written in Hebrew,

copies of Psalm 145 were found which include the missing verse:

When we

examine Psalm 145 from the Dead Sea Scrolls, we find between

the verse beginning with the

מ

(mem-top) and the verse beginning with the

ס

(samech-bottom), the verse beginning with the letter

נ

(nun-center). This verse, missing from the Aleppo Codex, and

missing from all modern Hebrew Bibles that are copied from

this codex, but found in the Dead Sea Scrolls, says:

נאמן

אלוהים

בדבריו

וחסיד

בכול

מעשיו

(The Lord is faithful in His words and holy in all His

works).

The missing verse

reads, “The

Lord is faithful in His words and holy in all His works.”

This verse can be found in the Orthodox

Study Bible,

which relies on the Septuagint. But this verse is absent from the King

James Version (KJV),

the New

King James Version

(NKJV), the Douay-Rheims,

the Complete

Jewish Bible,

and every other translation which is based on the Masoretic Text.

In this particular

case, it is easy to demonstrate that the Masoretic Text is in error,

for it is obvious that Psalm 145 was originally written as an

acrostic Psalm. But what are we to make of the thousands of

other locations where the Masoretic Text diverges from the

Septuagint? If the Masoretic Text could completely erase an entire

verse from one of the Psalms, how many other passages of Scripture

have been edited?

How many

other verses have been erased?

God's name is shown here in Paleo-Hebrew (top) and

in modern Hebrew (bottom). Modern Hebrew letters

would have been unrecognizable to Abraham, Moses,

David, and most of the authors of the Old Testament.

A Radically Different Alphabet

If Moses were to see

a copy of the Masoretic Text, he wouldn’t be able to read it.

As discussed in a

recent post,

the original Old Testament scriptures were written in Paleo-Hebrew,

a text closely related to the ancient Phoenician writing system.

The Masoretic Text

is written with an alphabet which was borrowed from Assyria (Persia)

around the 6th-7th century B.C., and is almost 1000 years newer than

the form of writing used by Moses, David, and most of the Old

Testament authors.

Adding Vowel Points

For thousands of

years, ancient Hebrew was only written with consonants, no vowels.

When reading these texts, they had to supply all of the vowels from

memory, based

on oral tradition.

In Hebrew, just like

modern languages, vowels can make a big difference. The change of a

single vowel can radically change the meaning of a word. An example

in English is the difference between “SLAP” and “SLIP”. These words

have very different definitions. Yet if our language was written

without vowels, both of these words would be written “SLP”. Thus the

vowels are very important.

The most extensive

change the Masoretes brought to the Hebrew text was the addition of

vowel points.

In an attempt to solidify for all-time the “correct” readings of all

the Hebrew Scriptures, the Masoretes added a series of dots to the

text, identifying which vowel to use in any given location.

Adam Clarke, an 18th

Century Protestant scholar, demonstrates that the vowel-point system

is actually a running commentary which was incorporated into the

text itself.

In the General Preface of his biblical commentary published in 1810,

Clarke writes:

“The

Masoretes

were the most extensive Jewish commentators which that nation could

ever boast. The system of punctuation, probably invented by them, is

a continual gloss on the Law and the Prophets; their vowel points,

and prosaic and metrical accents, &c., give every word to which they

are affixed a peculiar kind of meaning, which in their simple state,

multitudes of them can by no means bear. The vowel points alone add

whole conjugations to the language. This system is one of the most

artificial, particular, and extensive comments ever written on the

Word of God; for there is not one word in the Bible that is not the

subject of a particular gloss through its influence.”

Another early

scholar who investigated this matter was Louis Cappel, who wrote

during the early 17th century. An article in the 1948 edition of the

Encyclopaedia Britannica includes the following information regarding

his research of the Masoretic Text:

“As a Hebrew

scholar, he concluded that the vowel points and accents were not an

original part of Hebrew, but were inserted by the Masorete Jews of

Tiberias, not earlier then the 5th Century AD, and that the

primitive Hebrew characters are Aramaic and were substituted for the

more ancient at the time of the captivity. . . The various readings

in the Old Testament Text and the differences between the ancient

versions and the Masoretic Text convinced him that the integrity of

the Hebrew text as held by Protestants, was untenable.”

Many Protestants

love the Masoretic Text, believing it to be a trustworthy

representation of the original Hebrew text of Scripture. Yet, at the

same time, most Protestants reject Orthodox Church Tradition as

being untrustworthy. They believe that the Church’s oral tradition

could not possibly preserve Truth over a long period of time.

Therefore, the vowel

points of the Masoretic Text put Protestants in a precarious

position. If they believe that the Masoretic vowels are not trustworthy,

then they call the Masoretic Text itself into question. But if they

believe that the Masoretic vowels are trustworthy,

then they are forced to believe that the Jews successfully preserved

the vowels of Scripture for thousands of years, through

oral tradition alone, until the Masoretes finally

invented the vowel points hundreds of years after Christ. Either

conclusion is at odds with mainstream Protestant thought.

Either oral

tradition can be trusted, or it can’t. If it can be trusted, then

there is no reason to reject the Traditions of the Orthodox Church,

which have been preserved for nearly 2000 years. But if traditions

are always untrustworthy, then the Masoretic vowel points are also

untrustworthy, and should be rejected.

Excluding Books of Scripture from the Old Testament

The Masoretic Text

promotes a canon of the Old Testament which is significantly shorter

than the canon represented by the Septuagint. Meanwhile, Orthodox

Christians and Catholics have Bibles which incorporate the canon of

the Septuagint. The books of Scripture found in the Septuagint, but

not found in the Masoretic Text, are commonly called either the Deuterocanon or

the anagignoskomena.

While it is outside the scope of this article to perform an in-depth

study of the canon of Scripture, a few points relevant to the

Masoretic Text should be made here:

§ With

the exception of two books, the

Deuterocanon was originally written in Hebrew.

§ In

three places, the

Talmud explicitly refers to the book of Sirach as “Scripture”.

§ Jesus celebrated Hanukkah,

a feast which originates in the book of 1

Maccabees, and nowhere else in the Old Testament.

§ The

New Testament book of Hebrews recounts

the stories of multiple Old Testament saints, including a reference

to martyrs in the book of 2

Maccabees.

§ The

book of Wisdom includes

a striking prophecy

of Christ,

and its fulfilment is recorded in Matthew

27.

§

Numerous findings among the Dead Sea Scrolls suggest the existence

of 1st century Jewish communities which accepted many of the

Deuterocanonical books as authentic Scripture.

§

Many

thousands of 1st-century Christians were converts from Judaism. The

early Church accepted the inspiration of the Deuterocanon, and

frequently quoted authoritatively from books such as Wisdom, Sirach,

and Tobit. This early Christian practice suggests that many Jews

accepted these books, even prior to their conversion to

Christianity.

§ Ethiopian Jews preserved

the ancient Jewish acceptance of the Septuagint, including much of

its canon of Scripture. Sirach, Judith, Baruch, and Tobit are among

the books included in the canon

of the Ethiopian Jews.

These reasons, among others, suggest the existence of a large

1st-century Jewish community which accepted the Deuterocanon as

inspired Scripture.

Changes to Prophecy and Doctrine

When compiling any

given passage of Scripture, the Masoretes had to choose among

multiple versions of the ancient Hebrew texts. In some cases the

textual differences were relatively inconsequential. For example,

two texts may differ over the spelling of a person’s name.

However, in other

cases they were presented with textual variants which made a

considerable impact upon doctrine or prophecy. In cases like these,

were the Masoretes completely objective? Or did their anti-Christian

biases influence any of their editing decisions?

In the 2nd century

A.D., hundreds of years before the time of the Masoretes, Justin

Martyr investigated a number of Old Testament texts in various

Jewish synagogues.

He ultimately concluded that the Jews who had rejected Christ had

also rejected the Septuagint, and were now tampering with the Hebrew

Scriptures themselves:

“But I am far

from putting reliance in your teachers, who refuse to admit that the

interpretation made by the seventy elders who were with Ptolemy

[king] of the Egyptians is a correct one; and they attempt to frame

another. And I wish you to observe, that they have altogether taken

away many Scriptures from the [Septuagint] translations effected by

those seventy elders who were with Ptolemy, and by which this very

man who was crucified is proved to have been set forth expressly as

God, and man, and as being crucified, and as dying” (~150 A.D.,

Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho the Jew, Chapter LXXI)

If Justin Martyr’s

findings are correct, then it is likely that the Masoretes inherited

a Hebrew textual tradition which had already been corrupted with an

anti-Christian bias. And if we look at some of the most significant

differences between the Septuagint and the Masoretic Text, that is

precisely what we see.

For

example, consider the following comparisons:

These are not

random, inconsequential differences between the texts. Rather, these

appear to be places where the Masoretes (or their forebears) had a

varied selection of texts to consider, and their decisions were

influenced by anti-Christian bias. Simply by choosing one Hebrew

text over another, they were able to subvert the Incarnation, the

virgin birth, the deity of Christ, His healing of the blind, His

crucifixion, and His salvation of the Gentiles. The Jewish scribes

were able to edit Jesus out of many important passages, simply by

rejecting one Hebrew text, and selecting (or editing) another text

instead.

Thus, the Masoretic

Text has not perfectly

preserved the original Hebrew text of Scripture. The Masoretes

received corrupted texts to begin with, they used an alphabet which

was radically different from the original Hebrew, they added

countless vowel points which did not exist in the original, they

excluded several books from the Old Testament scriptures, and they

included a number of significant changes to prophecy and doctrine.

It would seem that

the Septuagint (LXX) translation is not only far more ancient than

the Masoretic Text . . . the Septuagint is far more accurate as

well. It is a more faithful representation of the original Hebrew

Scriptures.

Perhaps that is why

Jesus and the apostles frequently quoted from the Septuagint, and

accorded it full authority as the inspired Word of God.