A field of briars can be tilled into a bed of flowers, if gardeners but plan what they will plant, work the soil, and nurture their delicate seedlings. In the spiritual life, sinners can reach holiness, if they but clear the brambles of sinful thoughts by watchfulness, break up the hardened soil of sinful habits by bodily asceticism, and cultivate the fragrant blossoms of virtue through a life of repentance. In cognitive therapy, those with a psychological disorder can find some peace of mind, if they but uproot the weeds of distorted thinking with preliminary cognitive skills, reshape the landscape of selfdefeating actions with behavioral techniques, and prune back their maladaptive beliefs through advanced techniques for schema change.

Cognitive therapy provides clearly defined and carefully designed cognitive techniques for identifying and restructuring deeply held maladaptive beliefs that perpetuate psychopathology. In the Orthodox Church, putting off the old man and putting on the new entails a total immersion in a way of life that is guided by Sacred Scripture and Holy Tradition, nourished by the Divine Mysteries, and enlivened by the grace of God. In this context, the process of purification from the passions, illumination by the grace of the Holy Spirit, and deification in Christ also radically transfigure a person’s basic beliefs or schemata. This process is a gradual one, like unto that of a seed that falls to the earth, then sprouts and grows. Although spiritual fathers may plant and water, it is always God who gives the increase. For the believer, it is as clear as the noonday sun that the ineffable mystery of salvation is too vast and too divine to be compared with a finite number of psychological techniques that can induce enduring cognitive change. Notwithstanding, patristic advice aimed at shaping the way Christians look at the world can illustrate an alternative approach and provide a sense of meaning, a hierarchy of values, and a vision of the human person that can both direct Christian therapists who apply advanced techniques for restructuring their clients’ core schemata and warn Christian patients of potential dangers in their quest for improved mental health.

In this chapter, we will consider how the garden of the human soul can be cultivated by the trusty spade of patristic counsel and the calibrated gauges of cognitive therapy. Initially, we will focus on ascetic advice to the faithful on the daily struggle for virtue, the cultivation of good thoughts, the reading of spiritual books, and new ways of looking at themselves, others, and the world. In psychological terms, implementing this advice undoubtedly shifts fundamental beliefs of the believer, but not in the highly calculated fashion of the techniques for schematic change that we shall survey at the close of this chapter. Rather, as warmth from the sun, moisture from the rains, and nutrients from the soil help a seed grow into a plant, so illumined patristic wisdom gradually and gently guides the blossoming souls of believers to turn their heads toward the Sun of Righteousness and send down their roots to the Wellspring of living water. And in the process, the believer is transformed: “first the blade, then the ear, after that the full corn in the ear.”

Thus, advice of ancient fathers will form our gardener’s standard for finally examining how the flora of the human mind is altered in cognitive therapy through the extended use of techniques for achieving schematic change such as cognitive continua, schema diaries, historical tests, and psychodrama. Of course, in examining these tools for growing the prized mental flowers of a manicured psychological garden, we will not forget the proverbial lily of the field.

Patristic Advice for Tending the Garden of the Soul

Counsel for Daily Training in the Virtues at Home

As teachers of the Christian faith and way of life, the fathers were well aware of basic pedagogical principles such as the necessity to practice learned material consistently in order to apply it in real-life situations. Christian virtue, like every other art, requires daily practice and the support of others. The faithful are encouraged to study throughout the day whatever they gather from the texts of the liturgical services, from sermons given by priests, or from the advice of spiritual fathers in confession. According to Saint John Chrysostom, it is fitting for the faithful to form study groups at home and

review whatever they have gleaned in church before turning to the other tasks of day-to-day living. The saint also advises the faithful to be creative in their effort to become proficient in virtue. For example, when he encouraged his flock to refrain from saying anything derogatory about anyone else, he suggested that they work at home as a family unit both exhorting and correcting one another as well as devising ways to make this God-pleasing practice permanent. In general, he saw the home as “a training ground for virtue” [palaistra aretēs] where believers could experientially acquire the knowledge necessary for virtuous behavior in the marketplace of daily life.Orthodox monasticism likewise emphasizes the importance of spiritual training that takes place outside the explicit contexts of private and corporate prayer. The ascetics repeatedly urge monks and nuns to practice cutting off their will [ekkopē thelēmatos] daily in order to grow in virtue, to become humble, and to acquire compunction. Merely saying no to inquisitive thoughts about trivial matters cultivates a detachment from insignificant earthly concerns. Although it may not seem like a great accomplishment if a nun wonders what is for dinner, but refrains from asking the cook, over time this practice applied in a variety of situations establishes a proper hierarchy of values in her soul, shifting fundamental beliefs about her self and her world from the ephemeral to the eternal. Another example of patristic advice on planting precepts on virtue along the rolling hills of daily life is the practice of rehearsing in the mind how one would like to act in a troubling situation. For the fathers, this practice is scripturally rooted in psalm 118:60 (LXX): “I prepared myself and was not disturbed in keeping thy commandments,” which they paraphrase as “I reviewed in advance how I would handle a chance encounter by considering my resources, and I was not disturbed by tribulations for Christ’s sake.”

According to the ancient ascetics, this previous preparation enabled the three holy youths to enter the Babylonian furnace and hosts of martyrs to face martyrdom without being flustered. By anticipating and considering in advance what may take place, believers in the face of trials can likewise trim down excessive emotional reactions of fear or anger. For example, Saint John Cassian suggests that those who find themselves becoming impatient or angry should practice imagining that they are hindered, wronged or injured, but respond as the saints would—with perfect humility and gentleness of heart. Saint Nicodemos the Hagiorite likewise recommends that believers prepare themselves before going somewhere or coming into contact with irritating and exasperating people by imagining that others curse them and dishonor them, but that they weather it all with thanksgiving and peace of mind. Saint Theophan the Recluse expands this method to include all the conceivable encounters and imaginable feelings, desires, and reactions that a person might experience. He suggests reflecting on potential attacks at the beginning of the day and mentally planning how to react in a way that is in keeping with the commandments of Christ. This patristic practice also has classical antecedents. In the Christian redaction of Epictetus’s Encheiridion, those who desire to become virtuous are advised to consider in advance the potential difficulties and obstacles that they might come across in any endeavor.

They also prepare themselves mentally for the irritating or demeaning actions of others, so that they can remain calm and composed when encountered in real life. As an aid, they imagine how someone virtuous would behave in a similar situation. Given the Stoic pedigree for this practice, it predictably occupies a niche in cognitive therapy under the rubric of mental imagery techniques with the designation—cognitive rehearsal. In treating depression, it is used to help patients to identify potential obstacles that would prevent the completion of a therapy assignment. In treatment for anxiety, patients are instructed to imagine in advance what they would do in order to respond calmly in a particular stressful situation that they dread facing. Struggling daily to attain virtue, conversing with others about living in a God-pleasing way, cutting off the will, and mentally rehearsing Christian responses to difficult situations are simple practices, like mulching newly hoed soil. Nevertheless, they can gradually uproot core beliefs and perspectives that incite sinful thoughts, “for virtue, when habitual, kills the passions,” which is a theological way of saying that persistent, adaptive behavior dismantles maladaptive schemata. Most importantly, these exercises for righteousness’ sake help the believer to keep the commandments of Christ, the heavenly Husbandman who further illumines the meadow of the heart with the sunshine of divine grace.

The Cultivation of Good ThoughtsIn our previous two chapters, we discussed the concept of theoria or recollection in relation to praxis and watchfulness. For the ancient ascetics, theoria as the cultivation of good thoughts is an essential daily practice that brings order to the motley foliage of the human heart. It aims not at responding to specific thoughts, but rather at refashioning the overall way in which the faithful think by turning their attention to conceptual categories shaped by revelation. Saint Gregory Palamas defines the healthy thought-life in terms of thinking about the truths of revelation and the life in Christ in the same way as the prophets, apostles, and holy fathers did. To this end, monks of old advised the faithful to cultivate good thoughts or to engage in theoria, whose ultimate planting, growth, and fruition come from the very hand of God.

The Apostle Paul counseled the Philippians on the mental life writing, “Whatsoever things are true, whatsoever things are honest, whatsoever things are just, whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things are lovely, whatsoever things are of good report; if there be any virtue, and if there be any praise, think on these things.” According to Saint John Chrysostom’s commentary, this entails musing on virtue and on whatsoever is pleasing to the faithful and to God. Saint Isaac the Syrian notes that this remembrance of the virtues is a better way to elude the passions than resistance. This indicates that the cultivation of good thoughts works at a deeper schematic level than the methods for responding to individual bad thoughts that we examined in the previous chapter. Conscientious reflection on the virtues alters the way people interpret and thus respond to a variety of situations. For example, if Christians, who often reflect on the virtue of speaking truthfully, encounter a situation in which a lie could help them save face, their previous reflections will nevertheless lead them to admit the truth. In like manner, those who frequently ruminate on patristic advice about fighting anger will be more apt to apply that advice in time of need.In psychological terms, the cultivation of good thoughts has developed new schemata that alter the faithful’s perception of a situation and the value they assign to potential choices. This practice can exert a powerful influence on people’s lives. By daily recalling the zeal with which they first chose the way of repentance, monks acquire new wings with which to continue their flight. By reflecting on the “bold deeds done by their fathers,” the martyrs discover within themselves the courage to fight in like manner, for “the brave and steadfast mind riveted to religious meditations [religiosis meditationibus] endures.” Thus, the active cultivation of good thoughts provides the believer with a corrective lens for properly viewing the world, even as the passions distort what a person sees. According to Saint Barsanuphius, good thoughts are like pigments that the believer applies to the painting of the heart and thereby makes it difficult for clashing colors to be knowingly added.

In addition to the psychological and moral benefit of this practice, the cultivation of godly thoughts also increases faith and brings the promise of consolation after death. Together with musing on the beauty of virtue, the cultivation of good thoughts also entails pondering on the basic truths of revelation and the human predicament. Saint John Chrysostom points out that the value of this kind of theoria is not merely intellectual and didactic. Those who unremittingly remember God not only choose to do what is right, but are also remembered by God who then gives them the strength to accomplish it. As an aid to the faithful, the ancient ascetics prepared lists of edifying topics to be sown in the soil of the believers’ hearts. For example, Saint Gregory of Sinai advises cultivating thoughts about God, the angelic ranks, created being, the incarnation, the universal resurrection, the second coming, eternal punishment, and the kingdom of heaven. Saint Peter of Damascus mentions the above subjects in his list, but also adds other more philosophical and personal topics such as the flux of time, the trials of human life, the soul’s plight after death, our faults, and God’s bounty toward us. The irrevocability and finality of these considerations form a layer of bedrock that stabilizes the human mind. They, moreover, establish firm beliefs about human finitude, value, and responsibility that powerfully shape the way that people view themselves, their world, and their future. In psychological terms, these concerns can prevent or modify those maladaptive forms of the cognitive triad (i.e., negative ways of viewing self, the world, and the future) that leave people particularly vulnerable to depression and anxiety.

Although all the subjects on these patristic lists are worthy of cultivation, the particular needs and spiritual maturity of the individual Christian dictate which topics should be emphasized. For example, Saint John Cassian prefers love of virtue and love for God to the fear of hell as motives for the life in Christ. Consequently, he advises keeping the love of the Lord at the immovable center of the mind. Saint John Climacus likewise praises the sublimity of thinking about love for God, the kingdom of heaven, and the zeal of the martyrs, but he also notes the universal effectiveness of reflecting on one’s departure, the last judgment, and eternal retribution. In other words, although the love of God is the most exalted of subjects, the harsh reality of death can soften even the most insensitive souls, encouraging them to turn away from arrogance, vain thoughts, and inordinate desires, as well as to follow an ascetic way of life. Such a radical reconsideration of basic priorities naturally entails a shifting of core beliefs. Saint Theophan the Recluse advises the believer to reflect on the above subjects upon wakening from sleep and to repeat a scriptural verse such as “Where shall I go? It is appointed unto men once to die, but after this the judgment.”

The daily cultivation of good thoughts or theoria complements the everyday practice of the virtues by further altering the faithful’s interpretation of the world around them. When people ponder on virtue, patristic advice for fighting the passions, the achievements of the saints, and the history of salvation, as well as their own future death and judgment, they domesticate the wilderness of their souls with fruit-bearing trees. Íot only is their inner life nourished by the truth of the gospel, but also their inner vision is clarified by the light of Christ that exposes the falsehood of the passions as well as the treachery of dysfunctional beliefs stemming from selfishness, irresponsibility,

and ingratitude.

The Careful Reading of Sacred Writings and Spiritual Texts

The reading and study of spiritual books are essential patristic tools for the cultivation of good thoughts throughout the day, even as bibliotherapy (i.e., the reading of appropriate books on the cognitive approach to a particular psychological disorder) is instrumental in sustaining therapeutic progress by enabling therapy to continue outside the office. Furthermore, as bibliotherapy continuously reinforces important points made during therapy sessions, so spiritual reading consolidates what the believer learns during the divine services and mystery of confession. Spiritual reading [lectio divina, theio anagnōsma] is such an important facet of both the Christian life and the health of the soul that Saint Ignatius Brianchaninov begins his advice to monks with an exhortation on studying the gospels and engraining the commandments of Christ in the mind, so that monastics might put them into practice. Saint Theophan the Recluse likewise emphasizes this practical and purpose-laden aspect of reading when he advises the believer who has finished perusing a text to “persuade himself not only to think exactly like that, but also to feel and act so.”

For the holy fathers, the spiritual benefits of reading sacred texts are manifold. The reading of scripture protects the faithful from sin, for it both makes them more sensitive to spiritual matters and arms them with expertise about how to withstand and overcome temptations. In psychological terms, reading increases awareness and provides additional choices for coping strategies. It also strengthens faith, steadies a wandering mind, gives rise to pious thoughts, illumines the heart, and guides believers to virtuous behavior. Saint Athanasius the Great notes that constant rumination on the law of the Lord is a necessary form of spiritual exercise that should be practiced regularly, so that good thoughts might lead a person to acts of virtue. When believers daily read familiar teachings with the same eagerness and thirst for sanctifying knowledge that they had when they encountered those teachings for the first time, then even the purposes of their hearts and the wanderings of their imagination are sanctified. Even as the cultivation of good thoughts shapes a person’s core schemata, so do daily spiritual readings, for as Saint Neilus the Ascetic notes, “Frequent reminders of good examples carve similar images within the soul.”

The ascetic fathers even maintain that extensive spiritual reading can heal a person’s evil memories by imprinting in the mind the remembrance of the good, thereby purifying the memories of the passions, and distancing the soul from distressing recollections. Spiritual readings moreover “fill the soul with incomprehensible wonder and divine gladness.” When a cognitive therapist assigns psychology books for the purpose of bibliotherapy, patients are expected to take notes on the material and their reaction to it. In like manner, ancient monastics recommend that the therapeutic reading of the saints’ writings be done with the diligence of zealous students who pay attention to every word. The primary aim of such careful reading, however, is neither effective reinforcement, nor the inducement of a metacognitive analytical state for schema modification, but the discovery of spiritual treasures embedded in sacred texts. As Saint John Chrysostom notes, “One sentence often supplies those who receive it with ample provisions for their entire life.” Consequently, spiritual reading should have greater potential for schema modification than standard bibliotherapy on account of the greater faith, trust, and hope with which believers approach inspired writings as well as on account of the grace of God that inheres therein. Since the faithful read scripture and the writings of the saints with an awareness that through these texts God may be speaking to them, it follows that they will also read humbly and prayerfully. In terms of practical instruction, Saint Theophan the Recluse advises believers to empty their minds, open their hearts, and pray to God before attentively and slowly reading sacred texts.

Of course, devotional reading should be commensurate with the believers’ spiritual maturity, which means that they can feasibly put into practice the teachings contained in the books they read. Saint Ignatius Brianchaninov advises monks to study works written for those living in community such as The Discourses of Abba Dorotheos, The Catechetical Homilies of Saint Theodore the Studite, and The Ladder of Saint John of Sinai, before reading texts written for solitaries such as The Ascetical Homilies of Saint Isaac and The Philokalia of Saints Nicodemos the Hagiorite and Makarios of Corinth. Saint Nicodemos himself advises those sick with the thoughts to read “sacred books, especially Saint Ephraim, The Ladder, The Evergetinos, The Philokalia, and other similar books.” Although their advice differs, both monastic masters emphasize that the selection of spiritual books is neither a haphazard process, nor an academic exercise, but a purposeful and practical endeavor that should ideally be under the direction of the believer’s spiritual father. Appropriate devotional reading thus fertilizes the garden of the soul with the spiritual nutrients she needs. At a psychological level, new memories are formed, virtuous approaches to the world are learned, and godly schemata are made available for adoption. Thus, in addition to the sacramental life and the life of prayer, the church fathers also recommend concerted work on the virtues, the cultivation of good thoughts, and spiritual reading as practical daily methods for transfiguring the soul into another Eden where the Lord God walks in the cool of the day and guides her in naming her world. These are indeed powerful tools when used consistently over a lifetime, for like unto the rivers of paradise they water the soul with the grace and truth of the gospel of Christ.

Insight from the Inspired Words of the Saints

In chapter six, we discussed the prophetic aspect of spiritual fatherhood. When an elder, a priest, or a monk offers a word from God to a soul in need, that word can potentially transfigure the way that soul sees God, herself, and her world, thus bringing about what cognitive theorists would call schema restructuring. The tradition of seeking a prophetic word is especially evident in The Sayings of the Desert Fathers that frequently recount tales of a sojourner entreating an elder: “Give me a word.” With a fatherly word comes a flash of insight, and suddenly the struggler finds himself deftly grafted onto Christ the True Vine and in a position to bring forth much fruit. We will thus complete our pastoral description of the tools the fathers employ to tend the garden of the soul by considering the form and content of some of the God-given words present in the tool shed of patristic correspondence, homilies, and sayings. God’s love, providence, and ultimate designs for humanity. Every human being is precious in God’s sight and greatly loved. The church fathers never tire of sowing this fundamental Christian truth in the hearts of those who turn to them. It is a truth that expands the outlook of believers to encompass their ultimate destiny and God’s providential care for their salvation.

In cognitive terms, this certainty instills new core beliefs about self, others, and the future that act as a corrective lens for viewing the ills to which flesh is heir. For example, Saint Basil the Great once told a discouraged soul, “Everything is governed by the Lord’s goodness. We do not have to be distressed by anything that befalls us, even if it currently affects us in our weakness. Even if we are ignorant of the reasons why trials come and are sent as blessings from the Lord, we should be convinced that all things happen to us for our own good, either to reward our patience or to preserve our soul lest she linger too long in this life and be filled with wickedness.” Although people may not be able to understand the wisdom that governs individual struggles, by patiently enduring them they can gain a crown. Saint John Chrysostom similarly suggests that believers give thanks to God for whatever happens, even if they do not fathom why it occurs, for the Lord loves us even more than our parents do. From this perspective, one can understand why the holy fathers believe that “trial is profitable for every man.”

Thus, ancient ascetics would guide the faithful to interpret whatever happens to them through their trust in God’s providence, wisdom, and love that looks after their growth in virtue and aims at their eternal well-being. This humble trust then shapes or reshapes their innermost thoughts about themselves and their world, leaving little room for impatient demands stemming from sickly self-pity. Knowledge of God’s justice and tenderhearted compassion, moreover, endows believers with the courage to brave adversity, for this knowledge assures them that trials will prove that they are good or make them better. Trust in God’s providence and love is not nebulous optimism, but rockhard faith in the personal significance of Christ’s salvific work as a means for overcoming life’s trials and tribulations as well as sickness and death. Saint John Chrysostom beautifully illustrates how profound faith can transfigure one’s interpretation of the most grievous tragedies. To parents who lost their beloved son, he advised, “When you see the eyes closed, the lips shut, and the body motionless, do not have thoughts like these: ‘These lips no longer speak; these eyes no longer see; these feet no longer walk; but will all fall into corruption!’ Do not say such things, but the very opposite: ‘These lips shall speak of better things; these eyes shall see things greater still; these feet shall mount on the clouds; and this body that now rots away shall put on immortality. And I shall receive my son back again even more glorious.’”

Faith in the Resurrection of Christ gives the Christian the strength and courage to view life and death from another perspective that brings acceptance of trials, healing of wounds, and ultimately the hope of the saints. As a general approach to encounters with others, Saint Isaac advises the faithful to keep in mind that they “receive help from every man by God’s secret command.” They can even view distressing or insulting individuals as physicians [hōs iatrou] and their actions as healing medicines [hōs pharmaka therapeutika] sent by Christ for their purification from the passions and spiritual health. Saint Philotheus of Sinai likewise suggests that believers turn their thoughts from the injury or distress that others provoke to the deeper purpose cloaked by the affront. From a cognitive perspective, patristic advice on looking through unpleasant situations to God’s providence and the soul’s health provides new categories (schemata) for interpreting reality.

The value of self-reproach.

Alongside recalling Divine Providence, ancient monastics also advise the faithful to use self-reproach as a basic interpretive principle in order to avoid judging others who sin as well as to prevent agitation, anger, and pride. For example, when Saint Dorotheos would notice a brother failing in some way to lead a Christian life, he would say to himself, “Woe is me, him today and surely me tomorrow.” Thus, whenever observation would bring harm rather than benefit, the saint would deftly switch from a critical observer mode to a repentant introspective frame of mind. He formulated a rather simple algorithm for interpreting life’s vicissitudes: “If something good takes place, it is by God’s providence [oikonomia]; if something bad happens, it is on account of our sins.” As in other instances in the works of Abba Dorotheos, the aim of this rubric is not to provide simplistic answers to life’s complexities, but to encourage traits of gratitude and humility at all times through what cognitive theorists would describe as a fundamental change in core beliefs or schemata about the self and the outside world. In the case of insults and perceived wrongs, Abba Isaiah would tell monks to search their conscience whenever a brother speaks unkindly to them, for somewhere in God’s eyes they have sinned. As a rule of thumb, Elder Païsios counsels believers to always consider how much they are at fault, rather than how much their neighbor has wronged them. Saint John Cassian suggests that the irritated ascetic remind himself how he had planned to get the better of all his bad qualities and how a gentle breeze caused by a troubling word shook his entire house of virtue. In other words, the disturbing word becomes an opportunity for humble honesty that is the foundation of genuine self-knowledge. Abba Dorotheos likewise enjoins the grieved to stop brooding over their grievances and refocus on silence, heartfelt repentance, and prayer.

Of course, it can be challenging for people to reproach themselves when a reasonable assessment of a situation clearly indicates that they are innocent. Saint Nicodemos the Hagiorite offers a number of aids for self-reproach in such instances. For example, he suggests that believers bring to mind other faults where they were clearly responsible and to view the present difficulty as a penance imposed for them. Alternatively, they can recall that tribulations form the entryway to the kingdom of heaven, that adversities line the path of Christ and his friends, and that everything that happens on life’s journey is permitted by God. Consideration of the opposite point of view. Sometimes in lieu of self-reproach, the church fathers try to help the faithful to cultivate a Christian perspective by exhaustively examining an alternative point of view or the other side of an argument. Citing a saying attributed to Hippocrates, Saint Jerome notes, “Opposites are the remedies for opposites.”

This principle lies at the root of the patristic practice of listing a plurality of counter-arguments so that believers might be persuaded that their misguided convictions or conclusions are mistaken. For example, in the case of thoughts of despair, Saint Nicodemos the Hagiorite arms the spiritual father with the following arguments to counter despondent ruminations: (1) despair over sins ignores the existence of God and in Manichean fashion elevates vice to the rank of deity; (2) it fails to draw the conclusion that the Lord still accepts the sinner from the fact that the sinner is still alive; (3) despair is a trait of the devil, not of a struggling Christian; and (4) it is inconsistent with the witness of scripture that clearly narrates how the Lord accepted sinners of every ilk. In the case of a lack of contrition over sins, the spiritual father counsels the hard-hearted to consider their own responsibility for the loss of grace, for their exile from the blessedness of paradise, and for the decision to follow the path that leads to perdition. In the case of vain thoughts, he advises the careless to consider that one day they will give an account for every idle thought, that vain musings crowd out salvific reflections, and that pointless reverie often harbors bad thoughts in nascent form. Consideration of the perspective and plight of others. At other times, the holy fathers assist believers in acquiring a new way of interpreting painful situations by having them step back from their own problems and consider the plight of others. This basically Stoic approach naturally undercuts egocentric beliefs and tendencies. The Christian redaction of The Encheiridion provides a classic example: “If someone else’s servant breaks a cup, the answer is ready: those things happen. When you break your own cup, you should likewise respond as though someone else’s cup were broken, and then react in like manner with more important things.” Detachment and distancing from sources of distress naturally moderate emotional reactions and allow for a rational and objective response to problems. Although the church fathers do not reject this humanistic philosophical approach, they always supplement it with faith in Divine Providence. For example, Saint Basil the Great comforted a friend whose son had died, by urging him stoically to remind himself that “life is full of similar misfortunes” and as a Christian to believe that “earth has not hidden our beloved, but heaven has received him.” Later, the saint instructed his friend’s wife to think about others who have passed through such trials victoriously, on the inevitable mortality of all human beings, and the shining example of the grieving who comfort those who mourn.

In a similar vein, Saint Ambrose advised those who lament the loss of a loved one to remind themselves not only that death is common to all and often a release from the miseries of this world, but also that the grace of the Resurrection together with the assurance that nothing perishes in death, can assuage every grief and dispel every sorrow. Saint Theodore the Studite similarly counseled his banished friend Thomas to consider how all humanity is exiled from paradise into these withering lands [thanatēphoron chōrion], but, nevertheless, the believer like the psalmist dares to hope that the Lord will lead his soul out of prison to confess his name. Finally, Elder Païsios masterfully combined both Stoic distancing and Christian trust in Providence when he noted that the best medicine for our troubles is to consider the greater trials of our neighbor, so that we will thank God for sparing us and have compassion for others. Reflecting on the last judgment and eternity. Occasionally, some fathers attempt to open believers’ minds to consider the long-term future repercussions of current choices. Although we have already examined this approach in our discussion of goals, we should note its importance in the acquisition of a Christian perspective on reality that affects people’s values and hence their core beliefs about themselves and their world. Cognitive psychologists are not unaware of this fact, for even secular therapists may invoke religious beliefs about the future and the sanctity of life in order to counter suicidal ideation. Saint John Chrysostom repeatedly enjoins believers bravely to endure every trial “and soar above the attack of human ills by the hope in future blessings.” In other words, the faithful are to reframe their interpretation of their situation in eschatological terms. This interpretative framework recasts almsgiving and chastity, so that the balance is tipped away from greed and lust. In the struggle against temptations, the saint suggests that believers picture the judgment seat and repeat to themselves, “There is a resurrection, a judgment, and a scrutiny of our deeds.” This practice not only bridles sinful impulses, it also bolsters beliefs such as “I am responsible for my actions.” Other ascetics also suggest turning to God and bringing to mind the Last Judgment as a way of enfeebling bad thoughts. If the hope of eternal blessings does not provide sufficient motivation, sometimes the threat of punishment can be used to rouse the believer to contend more earnestly. At the very least, such prospects discourage the slothful from looking to death as a release from afflictions, for eternal suffering makes transitory anguish appear milder by comparison.

Considering the future as though it were already the past. At times, the church fathers would help believers to overcome troubling thoughts about the future by suggesting that they mentally project themselves to the time after the feared or desired event has already occurred. For example, Saint Maximus the Confessor approvingly quotes the Sophist Libanius’s axiom as a valuable antidote to sorrow and boredom: “If you wish to live a life without sorrow, regard those things that are going to happen as though they have already taken place.” Saint John Chrysostom makes a similar recommendation when he notes that the believer can douse the desire for glory by imagining that the envied position has already been attained, for afterward it loses its allure. In terms of schema reconstruction, this approach can help a person who defines his worth in terms of acquiring recognition (“If I become a lawyer, a doctor, or teacher, then I will be worthwhile”) to redefine value in theological terms (“All human beings are precious, because they are created in the image of God”). A variation on this approach can also be applied to encourage those in despair after a fall. In that case, however, the fallen are instructed to take courage by reflecting on how, after their restoration to health, they will one day use their experience to rescue others in danger of falling. Thus, they replace their present image of themselves as failures with an image of what they can still become by the grace of God, namely, physicians, beacons, and lamps.

Interestingly, cognitive therapists employ similar tactics to decrease the emotional distress of patients tormented by images of impending danger or failure. For example, anxiety sufferers often imagine a fiasco taking place, such as making a fool of themselves while giving a talk, and stop their fantasy at the point of embarrassment without going any further. The therapist can instruct such patients to imagine how they will feel a month or even a year after the mishap, so that they might gain enough detachment to put their fears in perspective and to see the extent to which they are exaggerating how terrible are the consequences of the worst-case scenario actually transpiring. Cognitive therapists have an arsenal of imagery techniques for dealing with their patients’ images of a feared crisis or terminal condition. In addition to techniques that involve patients jumping ahead in time and coping in their image that we also encounter in patristic texts, therapists also advise their patients to change the way an imagined scene ends, to question what they imagine as though it were an automatic thought, and to follow the imaginary chain of events to their ultimate conclusion.Protestant cognitive therapists sometimes enrich imaging techniques by having their patients imagine that the Lord Jesus is in an imagined scene. For example, people who are facing a difficult task are told to visualize themselves accomplishing the undertaking with Christ by their side. One therapist instructed a patient trying to cope with a tragedy to envision herself as a branch in reference to Christ’s words “I am the true vine, and my Father is the husbandman…I am the vine, ye are the branches.” After this exercise, the patient reported feeling at peace.

The use of imagery. In the Orthodox Church, the holy icons purify the spiritual vision of those who venerate them with faith and love. Quite naturally, the church fathers would also use verbal icons or metaphors in order to alter spiritually unhealthy perspectives and to foster a Christian outlook. This practice can be traced back to Christ’s sayings and parables in which he employed metaphor and visual imagery to inspire the faithful to keep the commandments. Those who live according to the beatitudes are commended not as “good people,” but as “the salt of the earth” and “light of the world.” Saint Theophan the Recluse recommended, “If possible, do not leave a thought naked in reasoned form as it were, but robe it in some sort of image and then carry it into the head as a constant reminder.” This practice is consistent with the psychological finding that images can directly introduce new patterns into the network of schemata that guide a person’s responses to various situations.

The homilies and correspondence of the holy fathers abound with a forest of images that aim at altering the way believers approach various tasks and sets of circumstances. For instance, Saint John Chrysostom advised those sluggish at prayer to picture the awesome scene of the sacrifice of Abraham, complete with details like the wood, the fire, the knife, and the gates of heaven thrown open. Such images are emotionally and cognitively effective. They not only reshape the faithful’s understanding of the vital significance of prayer and their relationship to God, but also motivate them to strive to make their own prayerful supplications into a living sacrifice to the most High. This same image can also be used to rally those weary in fighting a host of temptations. For example, the saint also noted that although legions of thoughts rose up against Abraham when he was told to sacrifice his beloved son, the patriarch withstood them all and “God from heaven proclaimed him conqueror…the Olympic victor…not in this theater but in the theater of the universe, in the assembly of angels.”

Although believers’ lives may seem to be worlds away from Abraham’s sacrifice, Olympic contests, and the angelic hosts, by faith they find something equally noble in their attempt to draw nigh unto God and thus dare to imitate what their physical eyes have never seen. Images reminiscent of prophetic visions are especially apt at inspiring zeal for spiritual undertakings. For example, Saint Theodore the Studite advised those weary with fighting the thoughts to reframe their view of spiritual warfare by picturing the man of prayer as a fiery cherubim or a many-eyed seraphim who bravely wields the sword of rebuttal against every sinful provocation. Thus, by associating captivating images with spiritual activities, the ancient ascetics could enhance the believer’s convictions about the significance of those activities and thereby ignite zeal for undertaking them.

With full awareness of the leverage that anticipated reward and punishment exert on behavior, the holy fathers also used threatening and enticing images to favorably influence people’s judgment about alternative courses of action. For example, Saint Theophan the Recluse prods negligent believers to behave in a Christian fashion by having them form the threatening image of the sword of truth hanging above them and the chasm of death gaping in front of them. To stir his listeners to almsgiving, Saint John Chrysostom paints an evocative image of the splendors of an earthly ruler and then describes the awe-inspiring magnificence of the King of kings and Lord of lords, so that a desire for unfailing wealth and unfading beauty might become an incentive for virtuous behavior that enriches the soul. Often the images, which the ancient fathers would devise to portray vice, are far from flattering. Saint John Chrysostom once compared people who seek money, rather than the kingdom of heaven, to souls “exceedingly full of stupidity, no different from flies and gnats,” since in their short-sightedness they desire material lead in the presence of spiritual gold. Obviously, to avoid such characterizations, the avaricious believer must rethink basic priorities and aspirations. With similarly vivid depictions, Saint John Chrysostom tried to cultivate self-control in those prone to anger. On the one hand, he portrayed the enraged individual in repugnant terms as a “drunk with protruded eyes in the act of retching, vomiting, erupting, and covering the table with filth avoided by all.” On the other hand, he glowingly depicted the insulted person who keeps silent as a mighty warrior who slays the beast within and is proclaimed victor in the civil war for his heart.

Frequent reflection on such images may serve as deterrents to anger by altering the faithful’s assessment of the impression their anger makes on others and the personal significance of their controlling it. In other words, these images tend to reverse false beliefs about the strength and superiority that angry people dream they possess. If believers can accustom themselves to bring those images to mind at the time of irritation, they can shift their focus and strive to be on guard like sailors who save their ship from sinking by lowering the sails when they feel the winds blustering against their faces or like housekeepers who use fire for cooking and lighting the lamps, but never for setting their homes ablaze. This variety of images gradually restructures believers’ understanding about the use of anger as a response to thwarted desires, unforeseen difficulties, and perceived disparagement by making virtue’s victory over anger their primary desire, objective, and source of self-esteem. The application of biblical parallels to personal experience. One final characteristic method that the fathers so effectively use to reshape an individual’s perspective on his situation is to locate a parallel to his experience in Holy Scripture and consider how the biblical figure responded. For example, the fathers remind the infirm of the much suffering apostles, the sorely tried righteous, and the blessed Timothy who had sickness as a constant companion. As the sick person already resembles the saints in affliction, he needs but their courage and patience in order to resemble them in their virtuous response to suffering as well. Elder Païsios likewise recommended that those going through a trial recall the tribulations of the righteous and how we have made greater mistakes than they did, but suffer far less. Saint John Chrysostom explicitly refers to the therapeutic value of drawing biblical associations when he comments, “Remember your Master, and by the remembrance, you have immediately applied the remedy. Remember Paul, reflect that you who are beaten has conquered and the beater is defeated, and in so doing you have completed the cure.”

This cure is a new perspective on a familiar situation or in cognitive terms, the modification of schema about the self and the world. This scriptural approach is especially well suited to encourage those sensitive souls in despair over their sins. For example, Amma Syncletica would remind her nuns that Rahab the prostitute was saved by faith, that Paul the persecutor became an elect vessel, that Matthew the tax collector became an evangelist, and that the murderous thief was the first to open the gates of paradise. Since someone in despair can easily identify with the failures of others, such examples mesh perfectly with his despondent state, and yet they introduce to that state the miracle of repentance and the presence of God that break it wide open by directly modifying core beliefs about the meaning of a person’s view of the past and resolve for the future in terms of his relationship to his Creator and Redeemer. In The Spiritual Meadow, John Moschus relates the account of a monk who was distressed by his struggle with the thoughts and came to the conclusion that he had made a mistake in renouncing the world and that he would not find salvation. He came to an elder who did not directly dispute his thoughts, but had him look back to the time of the exodus and told him, “Know, my brother, that even if we cannot enter the promised land, it is better to let our carcasses fall in the desert, rather than to return to Egypt.”

Finding meaning for his experience in the example from scripture, the brother acquired a new perspective and a more comprehensive schema for understanding his situation, so that he was able to accept his weaknesses, to set more humble goals, and to return to his own struggle with calm determination. In the case of despondency over sins, believers not only have wrong beliefs about the irreversibility of their lapses, but also about God’s disposition toward them. For this reason, Saint John Climacus reminds the repentant that the Lord gave Peter the command to forgive a person who sins seventy times seven, and adds, “He who gave this command to another will himself do far more.” This assurance in turn counters disbelief in God’s forgiveness. Saint Theodore the Studite likewise suggests that the distraught recall that the Lord loves every human soul and always stretches out his hand toward those who repent. Saint Symeon the New Theologian advises the downcast to remember that they are not saved by their own accomplishments, but by the grace of God.

Thus, with the assurance of God’s love, with faith in divine forgiveness, and the hope of true repentance, the despondent can acquire the courage to emerge from their slough of despond. In summary, within the believers’ rich and variegated life of ascetic struggle and participation in the Holy Mysteries, they are initiated into teachings and practices that can transfigure their basic perspective vis-à-vis themselves, others, and their world. In particular, the daily struggle for virtue, the practice of cutting off the will, and the prior rehearsal of virtuous responses behaviorally reshape their values and their views about significant details of their lives. The cultivation of good thoughts concerning the beauties of virtue, the truths of revelation, and the inevitabilities of death and change together with spiritual reading cognitively instill both powerful categories of thought for appraising their situation and inspiring models for imitation. Finally, salvific words from the pulpit (ambon) or the confessional on God’s love and providence, the value of self-reproach, the plight of others, and the Last Judgment as well as the use of imagery and parallels from scripture can provide an epiphany that enables believers to see and interpret their lives in the clear light of Christ. Thus, the faithful who struggle to follow Christ entrust themselves to the Church’s care, and collaborates with the Husbandman of their souls to transform the wilderness of their hearts into gardens where virtue ever blooms. Beholding the change wrought in their souls, they exclaim with the psalmist’s voice, “This is the Lord’s doing; it is marvelous in our eyes.”

Working with Beliefs in Cognitive TherapyHaving considered some representative ways in which the believer’s conscientious participation in the life of the Church prunes back self-centered, irresponsible perspectives and nurtures a virtuous response to life, we can turn now to the highly focused and interactive way in which cognitive therapy identifies, modifies, and replaces maladaptive schemata that perpetuate psychological disorders.

Techniques for Identifying Schemata

In chapter four, we noted that the cognitive theory of psychopathology maintains that maladaptive schemata or beliefs are the templates for the production of distorted automatic thoughts that precipitate emotional distress. Consequently, the therapist starts searching for relevant schemata from his very first session with the patient. At the time of crisis when the patient is highly disturbed emotionally, automatic thoughts such as “I’m a failure” often express schemata directly. As the therapist garners data about the patient’s automatic thoughts in various situations, he tries to detect patterns and reoccurrences that reflect the patient’s views about self and rules for living, and thereby to make intelligent hypotheses about potential maladaptive schemata. To verify his conjectures, the therapist can employ a variety of techniques to ferret out the patient’s silent assumptions and tacit beliefs that form his “psychological Achilles’ heel.” The simplest identification technique is for therapists to question patients about the personal meaning of those automatic thoughts that provoke the strongest emotional responses. To access self-schemata, therapists can ask, “What does this thought say about you?” To elicit beliefs about others, they can inquire, “What does this say about other people?” To draw out schemata about the patient’s world, they can pose the question, “What does this say about life in general?”

Christine Padesky also suggests using the sentence completion technique in which therapist begin—“I am ”; “People are ”; “The world is ”—and the patient finishes the phrase, usually with a single word. For example, someone with an obsessive-compulsive disorder might fill in the blanks as follows: “I am a perfectionist”; “People are expected to do things my way”; and “The world is supposed to be ordered.” Another useful identification technique requires patients to complete questionnaires such as Weissman’s Dysfunctional Attitude Scale, Beck’s Schema Checklist, or Young’s Schema Questionnaire. These psychometric tests facilitate the identification of a variety of typical maladaptive beliefs. Patients read a series of statements such as “I need other people’s approval in order to be happy,” and rate how much they agree or disagree with each statement. The tallied scores then provide the therapist with a schematic profile of their patients and a good indication of their psychological strengths and emotional vulnerabilities stemming from beliefs about approval, love, achievement, perfectionism, entitlement, omnipotence, and autonomy.

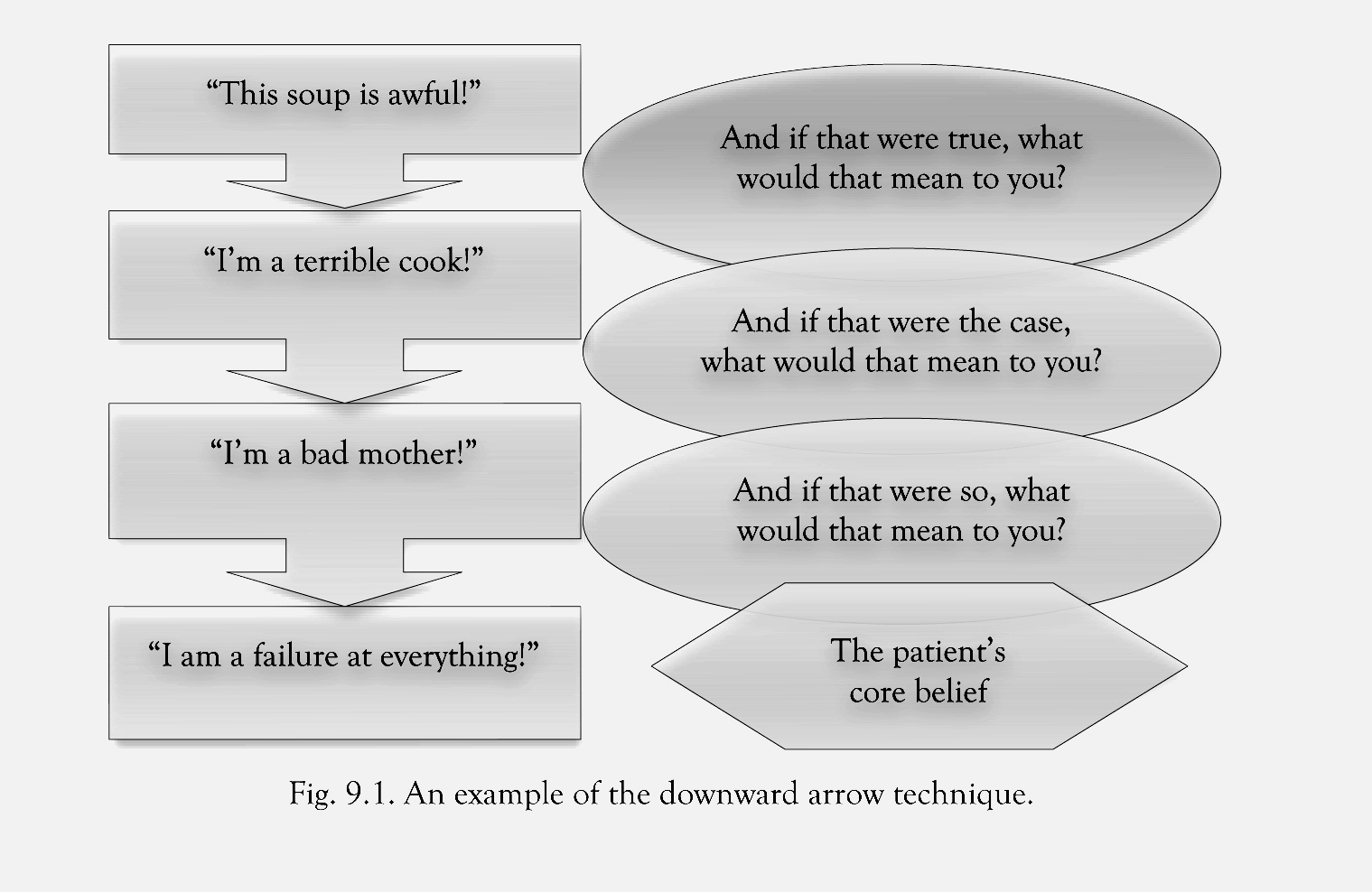

The third and most important method for the identification of problematic schemata is the downward arrow technique. Using this approach, the therapist asks the patient what it would mean if his upsetting cognition were true. The patient answers with another automatic thought that is then examined in the same way. They repeat this process, pealing off the layers and following the downward arrow until they reach a core belief. Although the downward arrow technique might appear to be prone to infinite regress, in practice the core belief is reached rather quickly. In particular, the therapist can infer that he has arrived at a core belief when the patient exhibits a noticeable shift in mood or starts repeating the same statement. For example, a depressed mother might taste some soup she made and feel sad after thinking to herself—“This soup is awful!” The downward arrow technique for this ostensibly insignificant automatic thought, illustrated in figure 9.1, reveals that beneath this typical evaluation lies a more problematic core schema about the self.

The patient’s core belief

Dr. David Burns astutely observes that the downward arrow technique guides the patient in a direction that is diametrically opposite to the dysfunctional thought record in which the patient tries to distance himself from an automatic thought and objectively evaluate it. Instead of invalidating the cognition with a rational response, the patient assumes what he subjectively feels to be true: namely, that his thought is 100 percent valid. He is then asked what it means to him or what is so bad about its being true. If the patient strongly believes in a given dysfunctional belief that has a broad impact on his life, the therapist then begins to utilize techniques for modifying that belief.

Techniques for Modifying Maladaptive Schemata

Once pervasive maladaptive schemata have been identified and the patient recognizes both how they contribute to his psychological distress and leave him vulnerable to future relapses, the therapist and the patient usually decide to work on replacing, modifying, or reinterpreting those schemata. Their first step is to identify an alternative belief that is more desirable. For example, the patient who believes she is unlovable would be asked, “If you weren’t unlovable, how would you like to be?” The patient’s answer (e.g., “I would be lovable”) would then be the goal for schema work through techniques aimed at weakening the currently held maladaptive belief and strengthening the newly defined alterative. An Orthodox Christian has reason for concern about the values used to determine the maladaptive schema and especially its ideal replacement. There has to be a better criterion for altering the way a person interprets reality than the hollow subjectivity of wishful thinking that fails to consider the human being holistically as a spiritual, moral, and psychological entity. Although most of the examples given in cognitive therapy manuals for clinicians are reasonable and result in an improvement in the patient’s quality of life, it is certainly conceivable for some suggestions for schematic replacement to clash with the Christian virtues of humility, chastity, patience, and self-sacrifice for the sake of the love of God.

Since schemata can be expressed in propositional form, many of the techniques that the patient has already learned to use for evaluating and responding to distorted automatic thoughts can be applied in order to gradually chip away at more deeply ingrained maladaptive schemata. Techniques include many behavioral approaches examined in chapter seven, as well as preliminary cognitive skills discussed in chapter eight. For instance, alternate perspectives, cost-benefit analyses, and Socratic questioning provide tools for re-evaluating old schemata, whereas behavioral experiments, acting “as if,” graded task assignments, and activity monitoring impart additional data for strengthening new beliefs. Rather than review all these techniques, we will just consider two representative examples in order to illustrate how they can be applied for the sake of schema change.

First, we have seen how patients used an advantage-disadvantage analysis in chapter seven to determine the best solution to a given problem. This same technique can also be employed to undermine a maladaptive belief that minimizes the consequences of harmful behavior. For example, someone fighting drug addiction may have a whole set of schemata that collectively make drug use seem desirable (e.g., “It’s just some harmless fun”). With the therapist’s guidance, the patient can fill out a 2 x 2 chart in which the patient tries to make an exhaustive list of the advantages of quitting and the benefits of not quitting as well as the drawbacks of quitting and the disadvantages of not quitting. Looking squarely at this diagram, the patient is no longer able to avoid noticing that the stark reality of drug abuse differs markedly from his Pollyannaish beliefs about recreational drugs.

Our second example is taken from the various techniques in chapter eight for distancing oneself from automatic thoughts and acquiring a new perspective in order to evaluate them. When the patient applies these techniques to schema modification, the contrast is not with a rational response to a given thought, but with a more functional approach that stems from a more adaptive core belief. By taking into consideration the beliefs of others, the individual can often step back from his own beliefs and then re-examine them more objectively. For example, the perfectionist patient may recurrently become anxious or depressed, because of a schema such as “If I don’t perform perfectly, I am a failure.” Such a patient could consider what he would tell a friend or imagine what he would tell his children, if they had the same dysfunctional belief causing them distress. The inconsistency between what the patient subjectively believes about himself and what he objectively holds to be the case for others then gives him enough distance to re-evaluate his belief.

Christian therapists sometimes endeavor to help their patients distance themselves from maladaptive beliefs by asking them questions such as “What would God think? What would Jesus do?” In the West, such pietistic questions are acceptable, especially given the emphasis of the Latin tradition on the humanity of Christ since the early Christian era. In fact, in his homilies, Blessed Augustine would find a present-day parallel to a situation described in scripture and ask, “What would the Lord do?”or elsewhere, “What would He have us do?” Likewise, Tertullian in his efforts to defend the gospel against various heretical groups asked questions such as “How would Christ speak?” or even “How would their own Christ act?” Although Orthodox Christians might understandably balk at the tone of the above questions out of deep reverence for the Second Person of the Most Holy Consubstantial Trinity, such questions can be reformulated in a more humble spirit and still have the same effect. Furthermore, Saint Paul did instruct the Romans to “prove what is that good, and acceptable, and perfect, will of God.”

Based on this passage, Saint John Chrysostom asked, “What exactly is God’s will [for us]? [His will is for us] to live as the poor with a humble mindset and disdain for glory, in abstinence rather than selfindulgence, in hardship rather than in ease, in mourning rather than in dissipation and laughter, and in all the other points that he has laid down for us.” Thus, Orthodox Christians could, and in fact should, ask themselves, “Given the divine commandments, what would a follower of Christ do?” As we saw in chapters three and four, core schemata are formed during childhood, reinforced over a lifetime, and consequently resistant to change. Therefore, schema modification requires considerable time, persistent effort, and special techniques both in session and at home. Among the more important cognitive instruments for schema change are cognitive continua techniques, positive data logs, core belief worksheets, the historical test technique, and psychodrama. If we liken these highly versatile tools to modern farming equipment and patristic methods to handcrafted plowshares and pruning hooks, our present examination of the above schema modification techniques should highlight yet again the functional similarities and worldview differences that have been the subtext of our study. First of all, the cognitive continuum technique is employed to modify dichotomous schemata by placing the problematic belief and its opposite, or alternative, on a scale with other specific examples that visually demonstrate the existence of gradations.

When patients come to realize that a given issue is not just black or white, their evaluation of themselves or others often shifts to a more moderate position. In practice, this approach requires the therapist and the patient to draw a line, to define the two extreme forms of the belief, to place them at the two endpoints of the line, to list relevant examples from the patient’s life experience, to assign their relative placement on the line, and then after examining the scale they have just constructed, to reconsider the initial belief. As an example of the cognitive continuum technique, Christine Padesky relates the case study of someone with chronic anxiety that was maintained on account of the belief “I will be punished for my faults” (See figures 9.2–9.5). With the therapist’s help, the patient formulated an alternative desirable schema: “I am safe, even if others see my faults.” In order to weaken the old belief and strengthen the new one, they constructed a safety scale on which the patient put an X to indicate how safe he felt when others noticed his faults:

Fig. 9.2. Step 1 of the cognitive continuum technique: constructing a scale.

The patient was then asked to define 0 percent safety and 100 percent safety and to write down those definitions beneath the two endpoints on the scale:

Fig. 9.3. Step 2 of the cognitive continuum technique: defining extremes.

The therapist then asked the patient to define 50 percent safety and to put that at the midpoint:

Fig. 9.4. Step 3 of the cognitive continuum technique: defining the midpoint.

Next, the therapist asked the patient to call to mind three recent experiences in which someone noticed a fault, to rate how safe he was in reality, and to place those responses on the continuum. The patient recalled his boss making

fun of him when he was unable to figure out the sales tax, his son being disappointed when the patient could not fix his son’s toy, and the therapist responding with understanding when the patient failed to complete his therapy assignment. The final form of this patient’s cognitive continuum is given below:

Fig. 9.5. Step 4 of the cognitive continuum technique: applying the scale.

Finally, the therapist has the patient compare how safe he expects to feel if someone notices his faults with how safe he actually felt when this happened. This process is then repeated throughout the week with new experiences.

There are dozens of other useful variations to this technique for schema change. For instance, the criteria continua technique has the patient make a continuum for an important schema and its opposite, and then place himself on that scale. Next, the patient lists the qualities that define that schema, turns those qualities into continua, and rates himself separately on each derivative continuum. For example, in figure 9.6 a patient who viewed himself as weird made a continuum for normality and ranked himself as 0 percent normal. When the therapist asked the patient what are the qualities of someone who is normal, the patient answered, “having friends, holding a job, and being happy.” With the therapist’s help, the patient laid out his criteria for normality as a series of personal continua that he separately evaluated. Looking at the criteria, the patient could see that his ratings based on his own criteria for normality did not add up to his belief that he is 0 percent normal.

Fig. 9.6. A patient’s global continuum of normality and criteria continua. Taken from Christine

A. Padesky, “Schema change processes in cognitive therapy,” Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy

vol. 1 (5), fig. 1. Reprinted by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

The therapist and patient usually apply continua techniques on a regular basis over the course of six months. As the patient’s accumulated experiences supply additional data related to his new beliefs, his old schema is weakened and his new schema is reinforced, leading to an enduring change in perspective. Other continua techniques include two-dimensional charting of continua for schemata that correlate interrelated variables (e.g., “Getting close to people is painful”) and two-dimensional continuum graphs that contrast schema predictions with reality (e.g., “Perfection is a measure of worth”).In chapter four, we noted that the church fathers’ understanding of virtue as a mean between two extremes also counters dichotomous thinking.

Continua techniques can also reinforce this patristic position. However, a therapist who is uninformed about certain Christian values and virtues could conceivably use these techniques with a Christian patient to bring about psychological improvement, but unwittingly harm the believer’s spiritual life. For example, if the Christian, who believes like Saint Paul that he is the chief of sinners, were instructed to make a sin continuum in order to prove that he is not really so sinful, the exercise could dry up his tears of compunction and cool his zeal for repentance. In like manner, a therapist, who is oblivious to the spiritual value, grace, and joy of wholesome self-sacrifice for the love of God, could suggest that someone who sacrifices himself for the sake of others construct an assertiveness continuum that could promote more psychologically adaptive, but less Christian responses to life.

Furthermore, when a created being approaches the uncreated, no language from the created realm is adequate. One can simply apophatically point toward the divine with absolute negations such as infinite and unoriginate, while referring to the human reality via cataphatic appellations such as “I am but dust and ashes.” In other words, in the spiritual life, there is room for certain kinds of dichotomous schemata, as basic as the sacred and the profane, that should not be modified or restructured for the sake of illusory psychological gain.

Another important set of techniques for schema modification involves the use of diaries, journals, and positive data logs. These techniques help the patient to organize and to store new observations that demonstrate the inadequacy of older maladaptive schemata as well as the value of new ones. Patients usually find these techniques to be discouragingly difficult, because the facts that they are being asked to observe and write down are automatically

filtered out, distorted, or disqualified by their present maladaptive schemata. In other words, the therapist is requesting that patients record data whose very existence they strongly doubt. For example, a therapist may suggest to a depressed patient with the belief, “I don’t accomplish anything,” that he keep a notebook divided into sections for work experiences, social interactions, parenting, and being alone. Under each heading, the patient is instructed to list anything that he did or tried to do, for which he deserves some credit, and to review this log daily. Protestant therapists sometimes try to increase the impact of such logs by having the patient imagine how Christ would react to even the smallest of his accomplishments. In general, the type of diary selected can be modified according to the psychological disorder or maladaptive schema that causes problems. For example, a woman who expected to encounter awful and unmanageable catastrophes every day was told to keep a diary in which every morning she would list in one column predicted catastrophes and every evening she would write down what actually occurred. At the end of a month, she found that one out of five “catastrophes” actually took place.In marital counseling, couples are advised to make lists of enjoyable time spent together each day as well as any pleasing actions or words by the other spouse (that are rated in terms of importance), and then to review these lists at the close of the day and the end of the week. As they discover pleasant times spent with each other, they begin to actually look at each other as persons, rather than as the vilified images that they have in their minds. In patristic tradition, Blessed Augustine’s Confessions stands out as a singular example of autobiographical journaling. In his equally unique Reconsiderations, he notes that the process of writing down observations about his life and thought increased his fervor to approach God at the level of thinking and feeling. This observation is psychologically quite significant, since when both cognitive and affective systems are activated, deeper schemata become more accessible for modification. In other words, Blessed Augustine implicitly affirms the value of journaling for schematic change. In wider patristic tradition, many fathers collected, recorded, and organized sayings of elders and saints for their own personal edification and the spiritual enrichment of others.

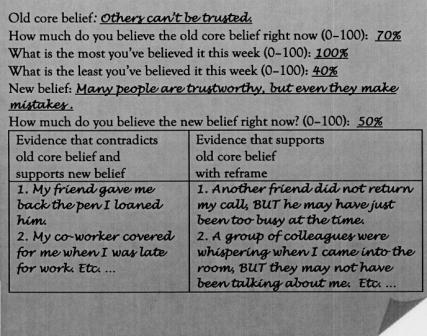

The above examples indicate that the proper use of the psychological technique of keeping diaries or positive data logs is not inconsistent with Orthodox Christianity. Significantly, Russian luminaries such as Saint John of Kronstadt and Father Alexander Elchaninov have availed themselves of diaries and memoirs for the sake of their own spiritual profit and the spiritual benefit of the faithful. Properly handled, journaling, together with the more widespread patristic practice of making collections of inspiring advice, can contribute to the cultivation of good thoughts that we examined earlier in this chapter. Another important tool for schema change is the core belief worksheet developed by Dr. Judith Beck. This worksheet calls for the patient to deploy rating and rational responding skills already honed by the dysfunctional thought record, but now employed weekly for the sake of schema change. At the top of the worksheet, the patient jots down his old core belief (e.g., “I am inadequate”), estimates how much he believes it at present (0%–100%), and rates how much he believed it during the week whenever he accepted it as probably true (0%–100%) as well as whenever he dismissed it as likely false (0%–100%). The patient then writes out an adaptive replacement for his core belief (e.g., “I am adequate, but human”) and reckons how much he currently believes it. Below this line there are two columns for the patient to record experiences during the week that confirm or disconfirm his core belief. In the first column, he lists data that contradict the old core belief and support the new one. In the second column, he records evidence that seems to support the old core belief, and then makes a rational response to it that interprets the evidence consistently with the new schema.

Fig. 9.7. Core belief worksheet. Format taken from Judith S. Beck, Cognitive Therapy (New York:

Guilford Publications Inc., 1993), fig. 11.3. Reprinted by permission of the publisher. All

rights reserved.

In figure 9.7, we provide an example of how the core belief worksheet could be used with someone suffering from paranoid personality disorder. Core belief worksheets, like schema journals, are tangible ways to help the patient recall and see new patterns. With time, the alternative schema will be strengthened to the point that the patient spontaneously uses it to interpret unfamiliar situations and thus acquires a broader range of choices for his interactions with others, along with more moderate emotional responses.In chapter four, we discussed the crucial role that childhood experiences play in the development of global maladaptive schemata about self and others. Although a person’s life history is an unalterable fact, his interpretation of that history is subject to change. Not only does a person’s schemata skew and affect what that person remembers, but efforts at recalling experiences incompatible with a belief can weaken it and strengthen a new belief. One formidable technique based on these principles and developed by Jeffrey Young is the historical test of schema, in which the patient examines evidence supporting both the old and new schema over his entire life history. First, the patient breaks down his life into segments that make sense to him, such as early childhood, elementary school, middle school, high school, college, employment, and so forth. Second, the patient begins to think about the first segment of his life: he brings to mind any negative memories that support his maladaptive schema (e.g., “I am unlovable”) and writes them down. Third, the patient struggles to recall positive memories that can bolster up his new more adaptive schema (“I am loved”) and records that evidence in the next column. Fourth, he tries to reinterpret and rationally respond to each memory that appeared to support his old schema, so that it will now be in harmony with his new one. Fifth, he writes down a summary for that segment of his life. In the course of therapy, the patient repeats this process for each period until he reaches the present, and then he makes a summary covering his entire life history.

Although patristic tradition may not offer such a systematic approach to the reinterpretation of one’s past, Blessed Augustine did have a quite sophisticated theory of memory, which even today retains its psychological value. The erudite bishop of Hippo was well aware of the benefit of entering “the fields and roomy chambers of memory where are the treasures of countless images,” for by so doing new memories can also be formed. He also perceptively noted that the individual’s understanding of his past is the basis for facing the future. In reviewing one’s personal history, it is important to recognize that memories are not the events themselves, but “footprints of the senses made in the mind by the images of things.” Some memories may be exaggerated by the mind; other remembrances may be out of focus, because at the time the will was concerned with other objectives. If a person possesses a good mind [bona mens], which is more important than an admirable memory, reviewing the past can help the believer see how God’s guidance prevented his downfall and that the Lord has not requited him with punishment that was his due, but has bestowed on him forgiveness and eternal life.

From an Orthodox Christian perspective, associating God’s mercy, compassion, and love with past memories can both heal the soul’s wounds and encourage the believer “to fight the good fight.” For example, when Saint Anthony the Great realized by divine revelation that Christ was invisibly present with him during his trials, he could look at them differently and thereby acquire increased vigor to struggle. A contemporary Greek Orthodox practice that can be seen as a spiritual historical review is the life confession [genikē exomologēsē]. Elder Porphyrios used to advise believers with psychological traumas or unresolved issues in the past to confess their entire life to a priest. While the person recounts pleasant and unpleasant experiences, the priest simultaneously prays for the person’s release from painful memories and asks questions from time to time as God leads him. The clairvoyant elder noted that when he would use this approach, he could see the grace of God enter and heal the wounded soul, releasing the person from the chains of the past and enabling him to begin life anew.

A final set of strategies for schema change in cognitive therapy has its origins in the emotionally charged techniques of Moreno’s psychodrama. In cognitive therapy, however, the aim of re-enacting schema-related incidents is not abreactive catharsis, but schema re-evaluation in its original context. During the re-enactment of a past event, other techniques such as Socratic questioning, as well as identifying automatic thoughts, emotions, and beliefs, can also be used to modify schemata that role-play brings closer to the surface. Sometimes early memories can be restructured by re-enacting traumatic experiences. First, the patient recalls the experience and relates it to the therapist. Second, they role-play the situation with the therapist taking on the role of the patient and the patient playing the part of the other significant figure. Finally, they switch parts and discuss what they have learned from the exercise. For example, Christine Padesky and Judith Beck relate the case of Jane, a woman with avoidant personality disorder who held the belief “I’m unlikable” from childhood. She recalled her mother yelling at her, “You’re so bad! I wish you were never born.” Using role-play, the therapist took the role of Jane’s mother and Jane played herself at the age of six. After the memory enactment, Jane reported her thoughts and emotions to the therapist. Next, they switched roles and Jane played her mother. At this point, Jane began to understand that her mother was very unhappy about her father’s desertion and that her mother’s comments were a reaction to her own unhappiness rather than an unalterable pronouncement that Jane was “unlikeable.” This was an important first step to altering this maladaptive schema.

Less emotionally intense role-plays can also contribute to schema modification. For example, rational-emotional role-play can help a patient who intellectually realizes that his maladaptive belief is irrational, but emotionally feels as though it were true. With this technique, the therapist argues against the belief, playing the rational side of the patient, while the patient argues for it, playing his own emotional side. When the arguments have been exhausted, they then switch roles and repeat the exercise. Protestant therapists sometimes do this kind of role-play between the sin-loving and God-loving aspects of the believer.

The Art of Gardening and Schema Modification